By Robert A. Lanier

Fascist! Since at least World War II, to call someone a fascist has been almost as insulting as to call someone a Nazi. In fact, “Nazi” has become a subspecies of the general term, “fascist,” because fascism historically was one of the inspirations for National Socialism (Nazism). Most people using the term really don’t know what it means. Today, the term has become one of strong opprobrium, used against someone the speaker doesn’t like or considers too controlling. The term is most often used by persons on the Left, rather than the Right, but the latter have learned of its impact and begun to adopt it.

There was a period, however, from the time of Fascism’s invention in the early 1920s until World War II began in 1939, when the Italian movement was looked upon with some admiration by many otherwise democratic people in Western Europe, Britain and the Americas. Strictly speaking, Fascism was largely invented by former Socialist Benito Mussolini to provide a rationale for his countrymen’s frustration with their lack of spoils from Italy’s participation in the World War, their fear of the disorder and economic chaos of postwar Italy and Europe, and their dissatisfaction with parliamentary government’s inability to solve the problems. At its core, it was made up of military veterans, petite bourgeoisie and angry workers. Using skillful propaganda, nationalist fervor and threats of violence, Fascists took advantage of government paralysis to offer promises of glory, work, and (most of all) order. They adopted black shirts in emulation of the red shirts worn by national hero Garibaldi and his men in the 19th Century.

By 1922, the king of Italy felt that he had no alternative but to appoint Mussolini to be Prime Minister, thus bypassing the usual electoral methods. Mussolini then arrogated to himself increasing powers over the entire social, political and economic system of the country, creating what he called “the Corporate State.” This was mainly a rationale for control by him and his Fascist pals. Order was restored (often by violent blackshirted thugs, called squadristi ), large public works projects were instituted, the military favored, and “the trains made to run on time,” supposedly. Opponents were jailed, if not beaten. Some were even killed.

For a Europe suffering from postwar upheaval and economic dislocation, the Italian model seemed attractive to many others than those on the far Left. Even in America, many people had been frightened by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the postwar recession, bombings and labor unrest in the period 1919-1923. The gaudy uniforms and public displays of the posturing Mussolini and his Blackshirts in photos and newsreels seemed worthy of admiration, if not emulation.

One successful public relations project of the Italian Fascist regime was its sponsorship of aviation. The 1920s were a period of fascination with the daring pioneers of the air. It must have seemed as though the skies were swarming with planes like gnats. It is hard for us now to realize with what awe people regarded flight at all, let alone flight over long distances. It was all new. There were no airports to speak of, no air traffic controllers—nothing.

In 1919, two British flyers, Alcock and Brown, were the first men to fly the Atlantic, and they did it in an open cockpit airplane. Other intrepid “birdmen” (as they were sometimes called, with somewhat unfortunate imagery) made or attempted spectacular flights with varying degrees of prudence or success. Some of them were Italian military fliers. However, the most famous flyer of all, of course, was young and handsome Charles Lindbergh, whose non-stop flight from New York to Paris on May 20, 1927, made him immortal. There were even flights by women, including Amelia Earhart, Amy Johnson and Beryl Markham.

The admiration given almost universally to these flyers resulted in countless receptions and honors. One of the Marx Brothers’ films even parodies a City Hall reception ceremony for uniformed flyers, with Harpo sporting a uniform and long beard. In 1933, during the Chicago “Century of Progress” world’s fair, 24 Italian military transatlantic seaplanes landed on the Lakeshore, led by handsome, goateed Fascist Air Minister Italo Balbo. So popular was the stunt that Chicago’s 7th Street was renamed “Balbo Drive,” and so remains at last investigation.

As we now know, Mussolini fatally aligned Italy with Nazi Germany in World War II, with disastrous results for his country, the Fascist reputation, and himself. But return with us now to a time when Americans could still regard Fascism and Fascists with at least tolerance, if not empathy. It was early May of 1927, a few days before Lindbergh lifted off on his epic journey.

Our subject, Colonel Francesco de Pinedo, was a small, well-groomed, cultured aristocrat who spoke English with a strong Italian accent and a slight lisp. He was 37 and his slicked-down hair was greying in 1927 when he and his crew began a series of flights across the Atlantic and around north and south America, which brought him briefly to Memphis, Tennessee. De Pinedo began his career as a navy man, having graduated from the Italian Naval Academy and served on a destroyer when Italy invaded Turkish-held Libya in 1911. In that war, Italy was the first nation to use aircraft for military purposes, and de Pinedo was inspired to join the Italian Navy’s air division. He was to fly reconnaissance missions during the First World War. After the war he helped to found the Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica) and promoted a program of demonstration flights by seaplanes. In 1925 he and his engineer flew their single engine seaplane, or “flying boat,” from Rome to Australia and Tokyo and back, some 55,000 miles.

In 1927, along with co-pilot Captain Carlo del Prete and mechanic Vitale Zachetti, he flew a seaplane called Santa Maria from Rome to the Cape Verde Islands and then on to Buenos Aires and Arizona. Unfortunately, on April 6, while refueling on Roosevelt Lake, a heedless youth threw a match onto the oily water, igniting it and the plane, which promptly sank. The Italians were able to raise the engine, however, and send it back to Italy.

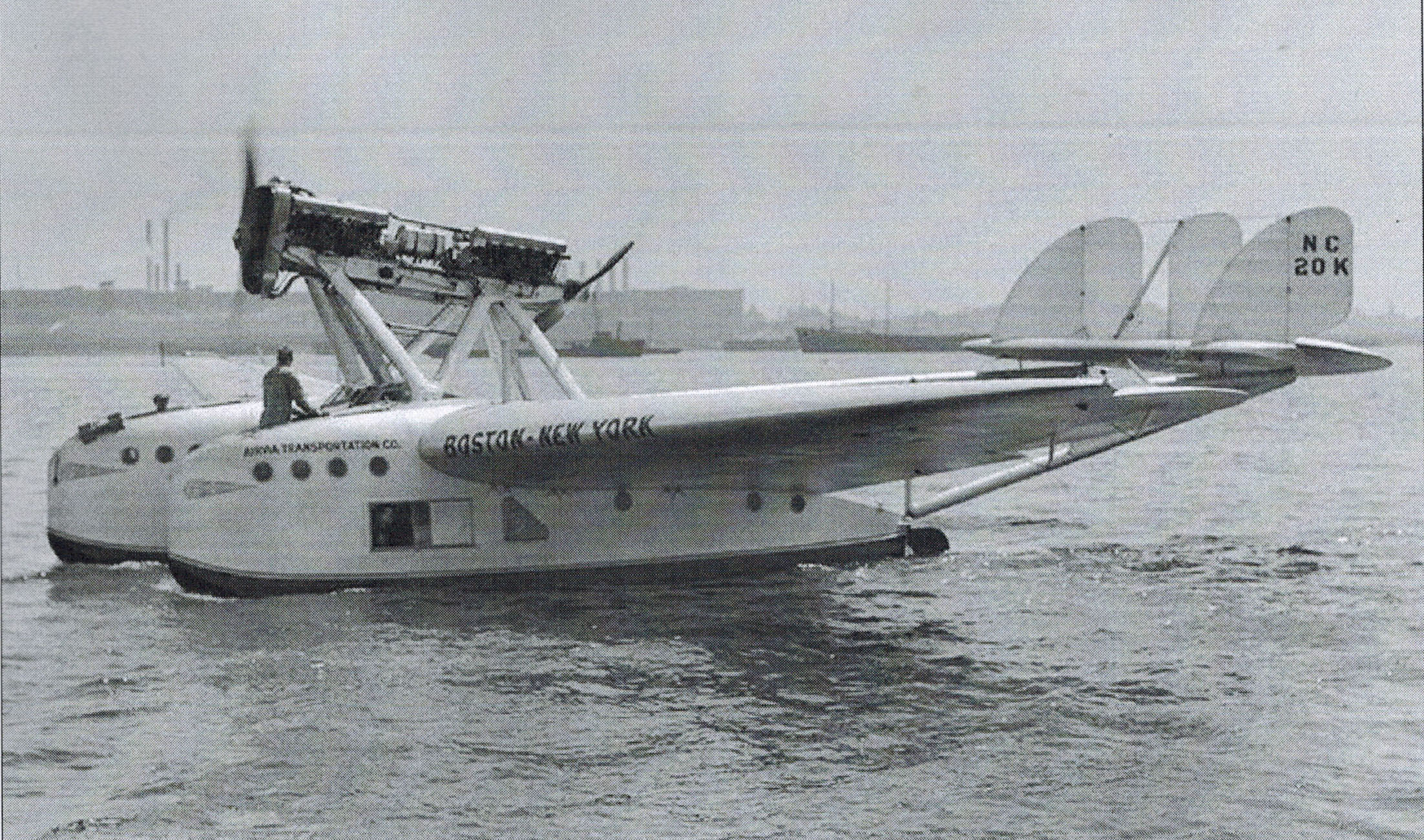

This was a setback to Italian and Fascist prestige which Mussolini could not permit, so he immediately ordered another identical seaplane sent to de Pinedo in New York by ocean liner. It was named Santa Maria II and de Pinedo flew it to the U.S. naval base at Boston, where he was greeted by the admiral in command, and the local Italian dignitaries and Consul. The replacement plane was a Savoia-Marchetti S.55 flying boat with a double tail, and fully fueled weighed 8 tons. The unusual engine, with propellers facing front and back, was mounted above on struts above the twin hollow pontoon fuselage and its wingspan was 72 feet from tip to tip. Painted on the fuselage, besides its name, was the slogan, Post Fata Resurgo, or “After Fate [Destroyed me], I Rise Again.”

Having learned of the intrepid flyers’ intention to fly around the country, Memphis mayor Rowlett Paine wired de Pinedo an invitation to stop in Memphis, which he promised “possibly” to do. Almost at the same time, a flight of eleven U.S. Army planes (the air force was then part of the Army) were due at the government’s semi-derelict Park Field, north of Memphis at Millington, on their way to maneuvers in Texas. Memphis was not to have a municipal airport until 1929. On May 11, John De Gaetani, the Italian consular agent in Memphis, received a telegram from the Italian Consul in St. Louis, reporting that de Pinedo and his men, (who had hopped from Philadelphia to Charleston to Pensacola to New Orleans), were due in Memphis on Friday the 13th for an undetermined stop.

Despite the unlucky date, Mayor Paine was notified at once by Judge John Galella, who had become chairman of the “entertainment committee” for the Italian flyers. A reception committee was promptly formed, pulling out all the stops. It included not only the mayor, but a large number of the leading citizens of both Italian and non-Italian extraction, many of them identified by their former military ranks. Numbered among the group were Captain Thomas Fountleroy, George Morris, G.V. Sanders, Colonel T. Roane Waring (head of the Memphis Street Railway Company), Colonel William J. Bacon, U.S. Senator Kenneth McKellar, Watkins Overton, Jack Carley, Major Thomas Cuneo, F. R. Gianotti, Louis and E.L. Gaia, W.M. Stratton, Dr. J.C. Dimarco, R. Raffianti, George Canale, G. DiLucca, Louis Foppiano, J.R. Buchignani, (former mayor) Frank Monteverde, Phil M. Canale, Louis Sambucetti, U.J. Gabrilesschi, Detective Sergeant Mario Chiozza, Major L.B. Chambers, Major M. Crawford, Jr. (representing the War Department), John Lingun, and Eugene Bizizza.

Memphis had just opened a small new landing field, called Bry’s Airport (because of a tenuous connection with the local Bry’s department store) just north of Jackson Avenue at the northeast border of the city limits. Its president, Edward Salomon, offered its use to de Pinedo, although how this was to be accomplished by his water-bound flying boat is unclear. Apparently Bry’s Field boasted two airplanes, and they were promised to be decorated with Italian and American flags and carry four of the welcoming committee to meet de Pinedo and “escort him into the city.” Lieutenant Vernon Omlie and his famous aviatrix wife, Phoebe, of the Memphis Aero Club were also to offer flights.

The flight of the Santa Maria II from Pensacola to New Orleans was made in a tropical hurricane and Colonel de Pinedo arrived there tired and a bit cranky, after all the receptions he had endured at each stop. After offering perfunctory thanks to the New Orleans Italian delegation, he turned to his plane and started fiddling with minor adjustments to it.

Early on the morning of his expected arrival in Memphis, Mr. De Gaetani received the disappointing word that, in order to be able to reach Italy in time for the May 25 celebration of the anniversary of Italy’s entry into World War I, the flyer was going to skip Memphis altogether and fly to St. Louis. Whether this was a ploy to avoid another tiring reception is unknown. However, as luck would have it, headwinds and a shortage of water forced the flyers to land on the river at Memphis after all, on the afternoon of May 14. The plane was moored to a sandbar two or three miles up the river, but ground swells washed it further inland, and a launch had to tow it to its resting place opposite the Post Office and Customs House on Front Street. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Edwin Williams, president of the Memphis Aero Club, eventually found a heavy enough anchor for the plane.

When Colonel de Pinedo emerged from the cockpit of the seaplane, those who had come to greet him on short notice were presented with a short man, dressed not in the traditional flying togs and goggles, but in a soft shirt, bow tie, dingy tan sweater and “plus fours.” (These were baggy knickers, popular with golfers). He donned a coat and fedora hat and greeted the greeters. Hopeful local Italian Americans suggested a banquet for the flyers while their plane was being refueled and watered. Sick of all the hullabaloo that had greeted him at every stop, the Colonel said bluntly, in his thick accent, “No. I don’t like them. I have business to attend to. Four minutes is long enough for any man to eat a meal.”

Fate intervened, however, and the Santa Maria II’s radiator started to leak. The Colonel turned to the hundreds of swarming greeters and resignedly said, “Oh, well. We stay here tonight. Tomorrow, we start at daylight and land in Chicago. We make no stops that we do not have to. We must hurry, and God being provident, we will arrive back on the Tiber on schedule.” With more time for conversation available, police sergeant Mario Chiozza spoke with the plane’s mechanic, Vitale Zachetti, and found that they had both been born in Milan. Ubaldo Andreucetti, editor of the Memphis newspaper for Italians, found that he and co-pilot Captain Carlo del Prete were both born in Lucca.

The spring of 1927 saw the infamous great flood of that year which inundated the entire Mississippi delta. De Pinedo had flown over it before reaching Memphis, and, despite his impatience with his delays, took time to comment upon what he had seen. “I saw houses floating away this morning. I felt sorry for the people. The flood is a great disaster. We were flying too high to see much of the country, but we saw water enough to realize the enormity of the flood. Of course, we have seen more water than that,” he added with a bit of self-laudation, “because we flew over the Atlantic Ocean and for a long time did not see any land at all.”

He was asked whether Mussolini would come to America. “I can’t say,” he replied. “He’s a very busy man.” When the flyer was asked when he expected to return to Italy, he said, “I hope to get back for May 24, God being provident. We have lots of flying to do and I can’t tell what will come up.” Asked about the French flyers, Nungesser and Coli, who were attempting a non-stop transatlantic flight from France to America, and who were overdue, he replied as might be expected. “Nungesser may or may not be alive. If he landed on some island, he may be safe. If he landed in the ocean, the chances are that unless he was picked up by a fishing boat, he perished. He had much bravery.”

The importunities of the welcoming party and the condition of his plane finally forced de Pinedo to agree to attend an informal dinner at the Peabody Hotel that evening. “Oh, well. For 20 minutes only,” he stipulated. Mayor Paine, who had been prepared to meet him the day before, missed his actual arrival. However, he visited the Italian at his hotel suite briefly, and wished him bon voyage. Speaking briefly at the dinner in his honor that evening, seated with his crewmen, Colonel de Pinedo expressed regret that he had originally telegraphed that he was skipping Memphis, because he had found the city to be “a wide-awake city, and I appreciate the enthusiastic reception the representatives of the Italian colony and native Americans gave us.” Most of the original welcoming committee were present, as were Mayor Paine’s secretary, Jack Carley, and the local Associated Press representative, P.I. Lipsey, Jr. The Colonel made his excuses to retire early, as he planned to leave at dawn the next day and head for Lake Michigan in Chicago. “With good weather, we should make it in four, maybe five hours. Then to rest tomorrow night, and another hop and we are in Montreal.”

Goaded by a reporter no doubt, he took the opportunity to give his somewhat bizarre interpretation of Fascism. “It is the hypocrite the Fascist hates, and not the sincere communist. We do not fight the communist when he is sincere. It is the hypocrite we have no use for. Some of the communists are all right.” Asked about reports that many persons who opposed Mussolini lay in prisons with no hope of trial, he replied testily, in a surprising mastery of the American idiom, “That’s a lot of bunk. Every one has the right of trial by jury. It is government by the people, a real democracy. What the people says is law.” When asked about Mussolini’s control of newspapers, he replied, “Oh, no. The papers can print what they wish so long as they tell the truth. But some of them, you know, keep up propaganda which is dangerous… When they do not tell the truth…” He then “made an eloquent movement with his hand,” it was reported. He said the Blackshirts had obeyed government orders to “lay aside their clubs.”

Shortly before dawn the next morning, the plane’s crewmen made their way down the riverbank cobblestones to the tethered seaplane and removed its protective covers. The Corps of Engineers motor launch towed the seaplane from its moorings on the Wolf River to midstream of the Mississippi, where the engine was started. The plane then laboriously proceeded southward until barely lifting under the Harahan and Frisco bridges, then turning north at 90 miles per hour. Waxing rhapsodic, the anonymous Memphis Commercial Appeal reporter described the departure of the aviators:

Like a graceful eagle, Colonel Francesco de Pinedo’s Santa Maria II lifted from the Mississippi River yesterday [May 15, 1927] at 6:15 o’clock and sped northward into the blinding rays of a bright May sun that turned the muddy waters of the flood-swollen stream into rolling waves of gold. [Author’s note: It is prose like this which reveals most reporters to be frustrated novelists].

Arriving somewhat late in Chicago, the airmen were nevertheless greeted by an enthusiastic group which included not only the combative, corrupt mayor “Big Bill” Thompson (who promised to “bust King George [of Britain] in the snoot” if he ever came to Chicago), but a gang of Blackshirts and gangster Al Capone.

Postscript

Overshadowed by Lindbergh’s feat, de Pinedo continued to fly around until 1933 when, dressed in a natty suit and carpet slippers, he crashed upon takeoff in a single engine monoplane while intending to fly from New York to Baghdad. His immediate incineration was filmed in a horrifying newsreel. The other famous Fascist flyer (and de Pinedo’s rival) met a similar fate. In Libya in 1941, while Italy was allied to Germany in World War II, Italo Balbo was killed by mistaken Italian anti-aircraft fire while returning from a mission of mercy, delivering injured British prisoners to medical care.

i The sources for this article are the respective Commercial Appeal, Memphis Press-Scimitar, and Memphis Evening Appeal newspaper issues of the time, along with “The Flying Machines,” in Memphis Sketches, by Paul Coppock, (Memphis: Friends of the Memphis & Shelby County Libraries,1976) p.122; Wikipedia, “Francesco de Pinedo”; “Park Field—World War I Pilot Training Field,” Vol. XXXI West Tennessee Historical Society Papers, pages 75,76; and Bill Bryson, One Summer. America, 1927 (New York: Doubleday, 2013) pp. 65, 79, 81, 135-6, 453-4.

Robert A. Lanier was born in Memphis in 1938, and has spent most of his life in the city as an attorney, with stints serving as a Circuit Court judge from 1982 until his retirement in 2004. Lanier also served as an Adjunct Professor at the Memphis State University School of Law (U of M) in 1981. He was a member of the Tennessee Historical Commission from 1977 to 1982, and was a founder of Memphis Heritage Inc., the historical preservation group still active today. He is the author of several books about Memphis history, including In the Courts (1969), Memphis in the Twenties (1979), and The History of the Memphis & Shelby County Bar (1981), and his most recent, Memphis in the Jazz Age (2021). Lanier also donated hundreds of his personal historic Memphis photographs to the Memphis Room of the Memphis Public Library – part of Lanier’s personal interest with Memphis history and historic preservation – and they can be viewed on the library’s digital archive and collection (DIG Memphis) under the Robert Lanier Collection.

Don’t miss these feature stories, Planning & Development news, and upcoming local happening in Arts & Culture. Sign up for our FRIDAY WEEKEND READS NEWSLETTER to receive our Weekend Reads, upcoming Arts & Community events and happenings, and for the latest on StoryBoard Shorts Doc Fest