“You never really know a man until you understand things from his point of view, until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

~Atticus Finch

In writing To Kill A Mockingbird, whether or not Harper Lee was inspired by the old adage – that we ought to walk a mile in someone’s shoes before passing judgment on them – matters less than the fact that to be empathetic on a physical touch and feel level is not easy to do.

It takes a great deal of thought, to get a real sense for how someone feels. Stories however, sure help.

In December of 1952, in the East Tremont neighborhood of New York’s the Bronx, the Fleischer family received a letter in their mailbox of their apartment building.

The letter, from Robert Moses, City Construction Coordinator, had also gone out to hundreds of other East Tremont residents, informing its recipients that the building in which they lived was in the right-of-way of the new Cross Bronx Expressway, and that it would be condemned by the city and torn down.

And, that they had ninety days to move out.

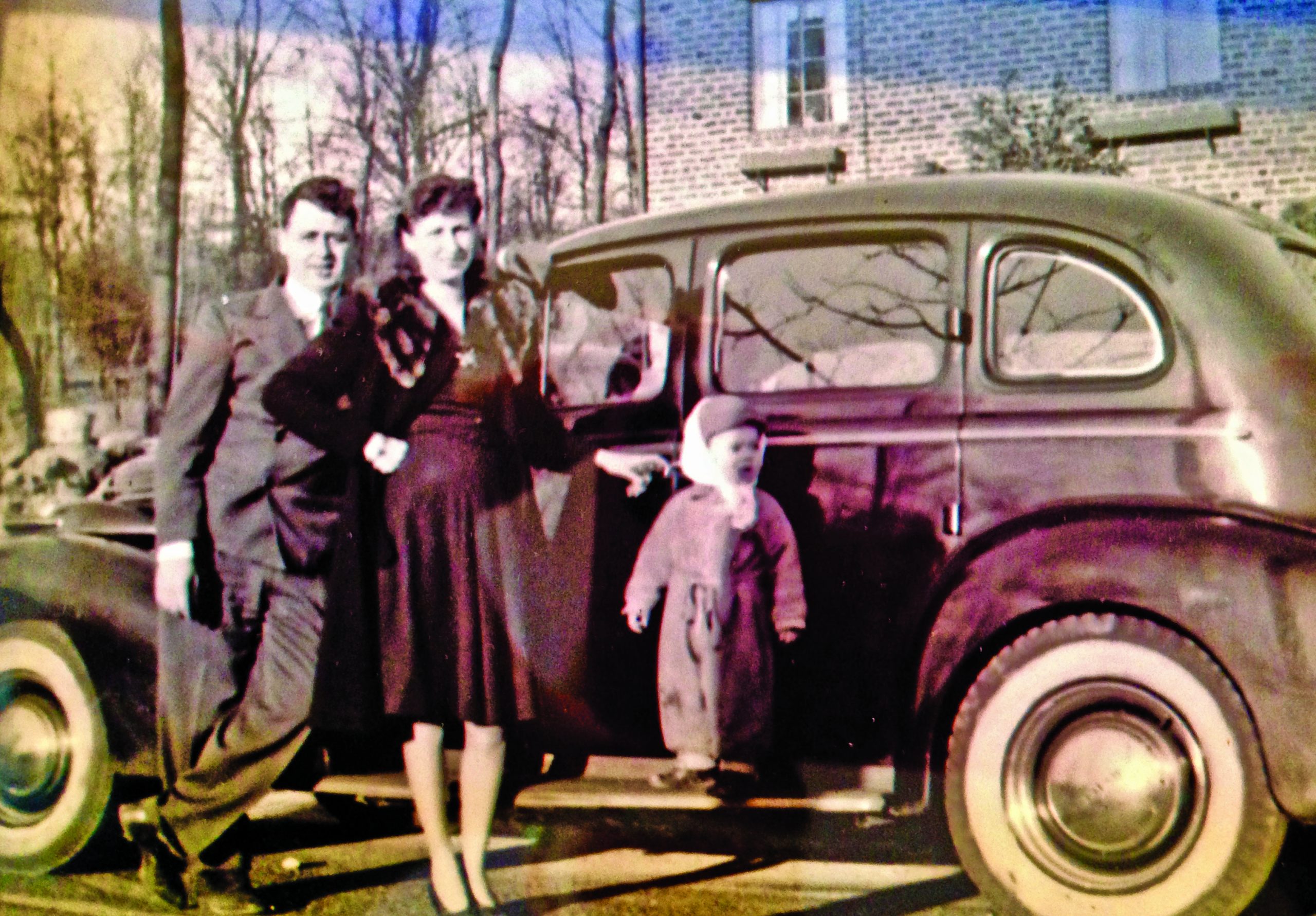

My grandparents, then in their middle 30s, my pre-teen father and my two uncles would later pack up the Buick and make a week-long trek to the sunshine and dreams of southern California. But they left their hearts in East Tremont.

When I was growing up, the memories of my family’s time in the Bronx was often a favorite topic after dinner. I heard story after story, usually repeated, of their days in nearby Crotona Park, of pickle barrels and pizza slices on East Tremont Avenue, of playing on the steps of the front stoop of their building on Bathgate Avenue and East 175th Street. I heard time and again where my grandma learned to pickle beets and where she got her recipe for chopped spinach with flour and beef stock (still a family favorite) from either a Jewish, German or Polish lady in the neighborhood.

They became engrained in my own memory, these stories, like a favorite childhood book you read over and over again: my grandpa’s commute on the Third Avenue El into Manhattan; his time driving a cab and his later work as a draftsman for Combustion Engineering on Madison Avenue and East 35th Street; my grandpa and the boys’ trips to Yankee Stadium to see Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra and a young Mickey Mantle play; the endless tales of the boys playing with the German, Jewish, Italian, Puerto Rican and Black kids in the neighborhood and in the park.

The family made a home in Long Beach, California, the boys went to school, married, had kids, etc. etc., but it was always clear to me that my dad’s and my grandma’s favorite days were those in East Tremont, before the trip to California, before the Moses letter, before the Cross-Bronx Expressway tore their neighborhood apart.

Years after my grandfather passed I would learn another truth: that my grandpa was never really the same after leaving New York.

All the promises of California never came to be for him. He had agreed to make the trip at the cajoling of his brother-in-law, visions of wide open spaces for his three boys, growing industry in Southern California, and perhaps out of some desperation with the sudden uncertainty of the fate of their Bronx neighborhood.

But whatever it was, I would learn that he had left his happiest days behind him in that old, immigrant neighborhood that Robert Moses had determined was slum-enough to bulldoze for his expressway.

Of course, this type of development in favor of paving the way for the automobile was happening to many of our older cities across the country. Pittsburgh, PA; Newark, New Jersey; Boston, Mass., San Francisco, California. They were all using the newly-available federal highway funds to build their roadways to the suburbs.

It all made sense at the time. People were going to have cars. Cities were getting dirtier and dirtier. The new suburbs had promises of fresh air and green lawns. And we needed vast, speedy highways to reach them.

Problem is, many of our cities were also using the new urban renewal, slum-clearance funds to bulldoze older neighborhoods to clear paths for the new roadways.

This also seemed to make sense at the time. If highways needed to be built that would inevitably carry cars away from cities, with the most efficient routes as possible, then the older surrounding neighborhoods would be directly in the way.

However these weren’t just any neighborhoods. They were the affordable neighborhoods, still close enough to the grime of the city, dense with tenements and apartment buildings, but attractive to the immigrant and our African American populations. After all, if you were a city planner reporting to city leaders you certainly weren’t going to suggest bulldozing any of the richer neighborhoods.

Hundreds of neighborhoods and hundreds of thousands of residents were displaced during the years of urban renewal. As you can imagine, most of this renewal occurred in black neighborhoods, and during years when redlining – restrictive, racial covenants in the selling of houses – was still very prevalent.

If you were the head of an African American family being displaced due to urban renewal or slum clearance and future neighborhood choices were narrowed due to racial restrictions, what were you to do?

Psychiatrist and author Mindy Fullilove, in her important book Root Shock, approached the treatment and evaluation of certain emotional pains this way: “When I bumped into the emotional pain related to displacement, I had the option of using labels like ‘post-traumatic stress disorder,’ ‘depression,’ ‘anxiety,’ and ‘adjustment disorders.’”

Here she was, evaluating emotional pain as related to having been displaced from homes and neighborhoods, and she settled on a term she would use throughout her book: Root shock.

To paraphrase, she equates the long-term emotional pain of being displaced from one’s home and neighborhood – uprooted – as to that of a traumatic disorder.

Her findings are convincing and the traumas run deep. They provide ample understanding as to why we experienced so much decay and rioting in our inner cities in the 1960s. And they can apply to the traumas no doubt felt by neighborhoods like Vance-Pontotoc, south and east of Beale Street.

I think back to my grandfather.

A white, Anglo-Saxon American male in his thirties and with engineering experience had no trouble finding work in 1950s Southern California. And he had his family. Soon he had a new home in a new suburb ten minutes from his job. Every five years he could buy a new Buick. He lived the typical middle-class life.

Yet with all that, he still never quite got over getting kicked out of his neighborhood in the Bronx.

I have tried to step into my grandfather’s shoes, to understand his version of root shock. Try as I may, I can hardly come close to the feeling he must have had when realized he was not in control of his own destiny, in a neighborhood he loved. If I can’t completely walk in the shoes of my own flesh and blood, how can I ever truly empathize with those so much less fortunate than me, who have lost homes and have been similarly displaced from their neighborhoods, often for the color of their skin?

Maybe I can’t. But I will sure try.

Welcome to the Equitable Issue.