This story was originally published in StoryBoard Memphis in November 2018

By Cathy Winterburn & Annesdale Park Archives

“When the next history of the city of Memphis is written a chapter will be devoted to R. Brinkley Snowden and T. Vinton. It will record unmistakable language their achievement in establishing the first subdivision of real estate in the South planned upon metropolitan lines, which adds materially to the beauty and welfare of the city. To their credit now and to their memory hereafter, Annes-dale Park will be a monument of the most beautiful and lasting type. The park was dedicated yesterday and six miles of paved streets and alleys, sidewalks and concrete gutters were deeded to the city of Memphis. The patriotic spirit, the faith in the future of their city and liberality shown by these gentlemen speaks more than words can, to their lasting quality of citizenship and to their value as members of this great and growing community.”

The Commercial Appeal October 15, 1903

In 1900, Memphis’s rapid industrial growth was creating a class of new-rich whose numbers made it impossible for all to find homes on the streets traditionally reserved for the city’s economic aristocracy. To accommodate this class, two prominent Memphis realtors, Brinkley Snowden and T.O. Vinton, developed Annesdale Park, in 1903. Because Annesdale was the “first subdivision of real estate in the South planned upon metropolitan lines,” it was officially known as “The First Subdivision of the South,” a designation that still appears on today’s deeds. Likewise, it is also believed to be the first Memphis subdivision where developers paid for streets and other improvements and then deeded them to the city.

The Greenlaw Addition, developed circa 1856, in what is now Uptown and The Pinch District, has also been referred to as “Memphis’s oldest” – i.e., first – subdivision. The Greenlaw Addition predates Annesdale Park by almost 50 years, Greenlaw could make the distinction of being the first planned, “mixed use” subdivision; in addition to houses, it was quickly the home to grocery stores, a brewery, a druggist, cobblers, and other retail stores. And yet, as we’ll see, city leaders in 1903 appeared dismissive of such prior developments as “patchwork sub-divisions of the past” as compared to the new Annesdale Park subdivision.

Boldface Names: Memphis City Founders

Brinkley Snowden named the new subdivision after the nearby Annesdale mansion, the Snowden family estate that had been named in honor of his mother. Snowden and Vinton acquired the land for Annesdale Park from the descendants of Anderson B. Carr. Carr and his brother Thomas came to the still-unsettled Memphis area in the fall of 1818. Passing through on their way to settle farther south, the Carrs decided to stay when they heard Andrew Jackson had just concluded the purchase of this territory from the Chickasaw Indians

In 1819, Anderson opened a trading house in partnership with Major M.B. Winchester, who had only recently arrived in Memphis. On about December 6, 1820, the Surveyor’s Office opened at Thomas Carr’s house on the fourth Chickasaw Bluff. Overton was present at this opening, with his plans for the building of a great city. When Overton failed to convince his associates to buy lots, he gave Thomas Carr two lots on which to build a tavern and Anderson Carr land for the construction of a mill. Prior to 1825, Carr purchased several downtown lots, and some authorities believe that he also acquired from John Ramsey, the holder of the original land grant, the property which eventually became Annesdale Park. Early records are confusing on the question of whether the Annesdale Park property was acquired from Ramsey or was granted to Carr as the site for a lumber mill.

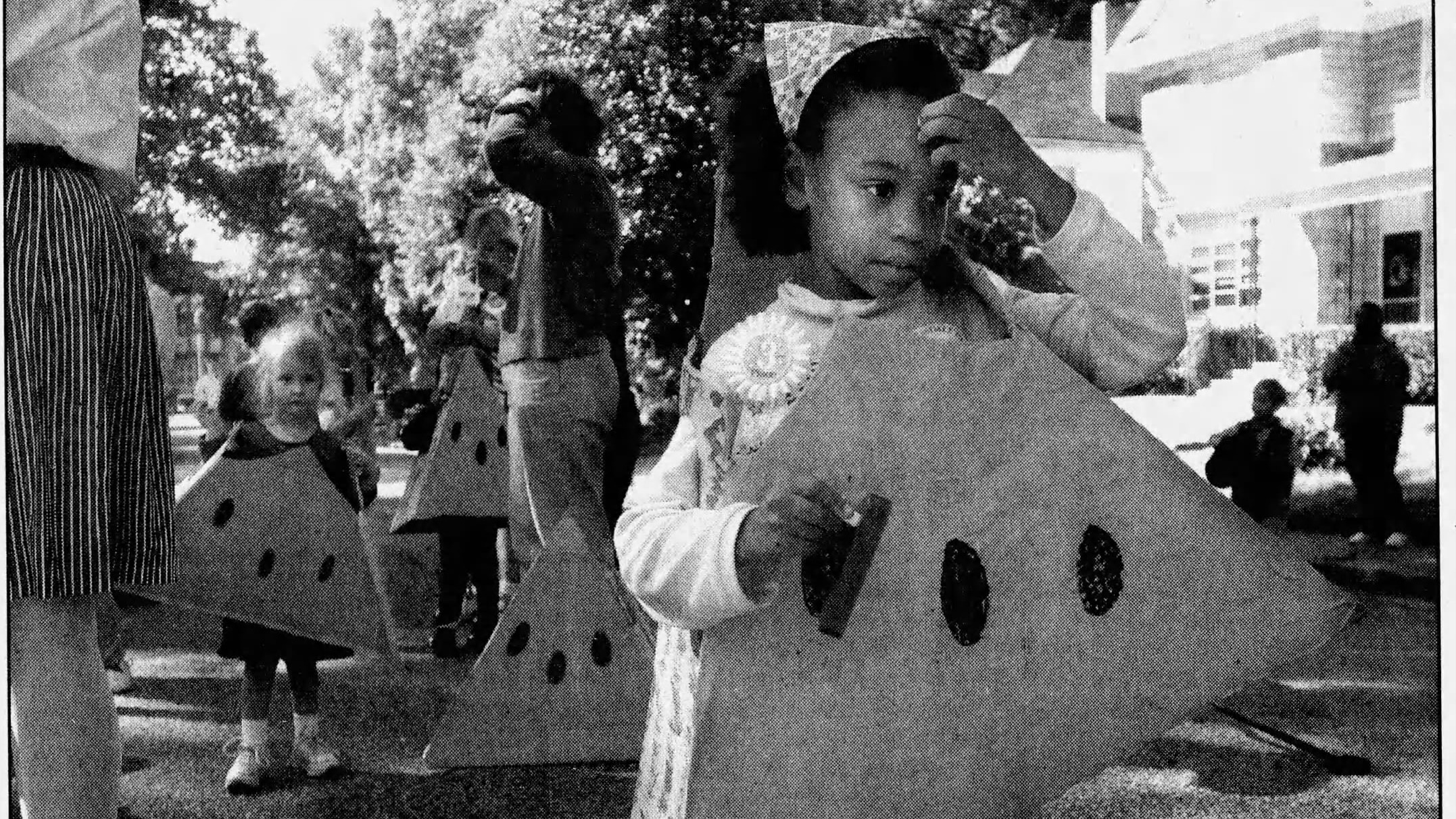

The Watermelon Legacy

When Snowden and Vinton acquired the Carr tract, it was “so cut with gullies and swamp lands that it was regarded as a bit of wilderness past any hope of recovery.” But Annesdale did not remain that way for long. When plans for the modern subdivision were complete, a fifty-foot sign with watermelon and a knife was erected on the Annesdale site. “In large circus-like letters the public was admonished to wait for the watermelon to be cut. ‘The watermelon was finally cut in the grandest style on the official opening date of Annesdale Park – October 14, 1903. The Celebration began with a luncheon at the Peabody Hotel for fifty of Memphis’s most prominent citizens, including, according to The Commercial Appeal, “the blood, the brains, the wealth, and the commercial sinew of the community.” During this luncheon, thousands of Memphis’s less prestigious watched a parade of fifteen wagons filled with watermelons led by all twenty pieces of Arnold Full’s Brass Band, rom Main Street to Annesdale. Each wagon was decorated with a banner announcing the Annesdale Park watermelon was to be cut. After the luncheon, the honored guests boarded the reserved cars of the Union Avenue streetline for Annesdale. This trolley line had only recently been extended to Raleigh Avenue (now Bellevue Blvd.) expressly to serve Annesdale Park.

“… a rift in the dark cloud of subdivision error…”

That afternoon, acting chairman W. Crawford opened the program by announcing from the grandstand that he represented the “liberal (Annesdale Park) company which has made possible one of the most significant enterprises in the history of the city.” He then introduced the orator of the afternoon, Caruthers Ewing. Ewing was a prominent young attorney and widely known as one of Tennessee’s most gifted orators. (In 1907, he moved to 1298 Vinton Ave in Annesdale.) On behalf of the Annesdale Park Company, Ewing presented the City of Memphis with deeds to Annesdale’s paved sidewalks, alleys and six miles of streets macadamized with slag and rock screenings and lined with concrete curbs. Ewing said Snowden and Vinton had spent more than $75,000 on these improvements and on the installation of the “latest park lamps” (gas streetlamps), sewers, and water and gas mains. (Electricity was added later.) “The idea,” said Ewing, “was to make it paradise. No impoverished nor plebian feet could ever trespass on the sacred precincts in the future,” he continued. Then as an after-thought he said no man could, under the rules of the company, become an owner of one of these lots unless he could show a certificate of good character and place himself under an everlasting peace bond. Memphis Mayor Williams accepted the deeds for the city, saying “We have looked upon (Annesdale) as a rift in the dark cloud of subdivision error that has hung over Memphis for so many years… the patchwork sub-divisions of the past and their promoters must be relegated to the rear by this march of enterprise and manly venture.” Mayor Williams then cut the watermelon, signaling the beginning of lot sales; the public was now entitled to buy “its slice” of this new subdivision.

“Phenomenal” Early Success, ‘60s Decline, ‘70s Reawakening

The majority of the homes in the subdivision were built between 1904 and 1910, though building continued until the mid-twenties, when all but a few lots were occupied. The neighborhood was a phenomenal success. In 1908, St. John’s Methodist Church was built at the corner of Peabody Avenue and Bellevue Boulevard. Bruce School was also completed in 1908. The Adjacent Bellevue Junior High School was built in 1927. During World War I, some Annesdale homes became boarding houses run mostly by war widows left to fend for themselves. After World War II, because of the acute housing shortage during and after the war, the city changed the Annesdale zoning to allow for conversions to multi-family dwellings. Some of the houses were converted to apartments with subsidies from the National Housing Authority, a federal war housing agency. This agency leased homes and with government funds converted them into apartments; after seven years the house reverted to the original owner, who was not required to repay any remodeling costs.

Because of this subdividing of homes and the subsequent flight to the suburbs in the late 50s and early 60s, the Annesdale neighborhood began to deteriorate. While some of the older residents stayed, many others sold to investors who further subdivided houses to make small apartments. Some Annesdale homes became boarding houses, nursing homes, and halfway houses. But in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, young professional couples began buying and renovating the grand old houses. With inner-city living gaining new status, this trend continued. Real estate prices rose and into the ‘70s almost every house that went up for sale was bought by a young couple eager to renovate. In the fall of 1976 a group of Annesdale residents, passionate about retaining the neighborhood’s character, formed the Annesdale Park Neighborhood Association. The group began by meeting each month to work on neighborhood projects and problems, and to foster an old-fashioned spirit of neighborliness among residents.

Note: Feature image from The Commercial Appeal, October 15, 2001, Courtesy of Newsbank.

Cathy Winterburn is the President of the Annesdale Park Neighborhood Association, a group that in 1976 joined other Midtown neighborhoods with the purpose of maintaining the unique character of their neighborhood