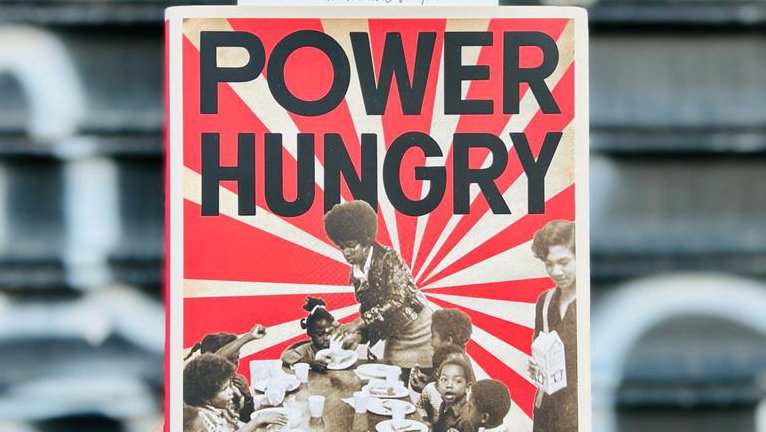

Suzanne Cope profiles Black women who used food to fight for freedom

By Aram Goudsouzian for Chapter16.org originally published January 12, 2022

We often associate the civil rights and Black Power movements with the dramatic, confrontational spectacles of marches, speeches, and mass demonstrations. In Power Hungry, Suzanne Cope tells a different kind of story. Her book profiles Aylene Quin, a restaurant owner in McComb, Mississippi, and Memphis resident Cleo Silvers, who joined the Black Panther Party and helped run free breakfast programs for schoolchildren. While spotlighting the roles of women in the Black freedom struggle, Cope also explains how the movement depended upon the most elemental of needs: feeding people.

Cope is a lecturer at New York University and a journalist who has written about food and culture for the New York Times, The Atlantic, CNN, and BBC. She is also the author of Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits and the Return of Artisanal Food. She answered questions via email from Chapter 16.

Chapter 16: How did you come to draw connections between food and the Black freedom struggle? What can food tell us about a movement for justice?

Suzanne Cope: Sit-ins at restaurants are often the first (and sometimes some of the only) stories told about the Black freedom struggle. As a food studies scholar, I was interested in digging deeper into these stories. I wanted to learn more about why these spaces were so important and about leaders who could model actions for activists today. I came across Aylene Quin’s name as owning a popular restaurant — South of the Border — as just a line or two in many histories of the time. I knew her story had so much more to it, and I really wanted to help amplify the work she did and find out why she was so powerful as a restaurant owner — so much so that she was targeted by the Ku Klux Klan.

The Black Panther Party, too, was considered dangerous by the FBI. In an internal memo, director J. Edgar Hoover specifically mentioned the danger posed by their Free Breakfast for Children Program.

What can food tell us about a movement? The very short answer is that it can literally feed people — like Mama Quin fed the activists, like the BPP fed the children. But it also models the world that these leaders want to see: where kids don’t go hungry, where Black people can eat alongside white people without fear, where people believe that food is a right and not a something to be given or taken away by the more powerful.

Chapter 16: Cleo Silvers was instrumental in running the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast programs. Why did they begin? How did these programs fit into the Panthers’ vision of revolutionary politics?

Cope: Interestingly, I found in my research that some of the same activists from Freedom Summer also helped teach the BPP to listen to the people they wanted to serve, to ask them how they could help. Feeding kids breakfast and making sure they got to school were common requests. The Panthers quickly saw how popular this program was — and how they could teach children about Black and Brown history, about their vision for revolution, over breakfast. It also modeled a vision where the community donated to feed the hungry, where children were taught that they mattered, where the families saw how the Panthers were there to help empower them. The breakfasts worked on so many levels — which is what made them powerful — and caused the ire of the FBI.

Chapter 16: What was the research process for your book? Did the COVID crisis affect it?

Cope: I wrote about this subject for an article in LitHub. More briefly, I was grateful to travel in early 2020, to visit McComb and meet some members of Mama Quin’s community, including her daughter Jacqueline (who was in the [family’s] house when it was bombed in the summer of 1964). I also was able to visit the local Black History Gallery; I didn’t realize how much this experience affected my understanding of Mama Quin’s story and this place and time until the pandemic stopped all travel.

I was also able to visit Cleo Silvers the same month, and we had such a wonderful few days together, cooking and eating and listening to music. I believe it helped us establish a relationship that couldn’t have happened in the same way over the phone.

Ultimately there were places I wanted to visit (or revisit) that I couldn’t because of the crisis — and I can never know what I wasn’t able to learn by mostly having to research from my home. But I do believe that this story is told well and fully from the research I had access to. It might have been a different book if I was able to travel more, but not a better book. I just hope this only starts the conversation on these women and this time and that I give someone else a jumping-off point to do more research.

Chapter 16: If historians center the experiences and perspectives of Black women such as Quin and Silvers, do the civil rights and Black Power movements look different? How might it change our understanding of this history?

Cope: One important perspective is the power and strength of female leaders. I utilize the scholar Françoise Hamlin’s term of “activist mothering.” It looks, in part, at the skills of women as nurturers as imperative to their effective leadership. But these skills, and leading in traditionally “feminine” realms (like food), were — and still are — long undervalued. Likewise, women consisted of at least two thirds of the BPP members and led many of their “survival programs” (focusing on items such as food, shelter, and clothes). Their leadership is long under-recognized for similar reasons. I also cite other scholars in the book who discuss the more narrow roles society allows Black women, and how that can limit them, and limit our broader perception of them. I hope that this book allows us to recognize these activist mothers — and the many, many others like them. I hope we can reimagine what leadership looks like and learn from that!

Chapter 16: In recent years, we have seen extraordinary activism and achievement, as well as sobering reminders of racial inequality. What lessons does Power Hungry have for today?

Cope: I believe we are starting to see a larger recognition of Black female leaders, and I hope we continue to look to women to help usher in change. I have also heard from readers that this was an important history lesson — that many didn’t realize the extent that the power structure was working against these activists and that there are many echoes of these issues we still experience today.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.