On the occasion of its 95th birthday, Part II of our series on the History of the Orpheum

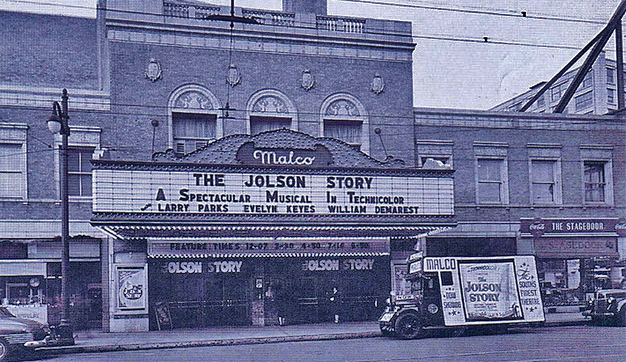

To generations of Memphians, it was simply “The Malco.”

It was the movie palace of all the movie palaces – grand places where Memphians took their dates, where parents took their kids on a Saturday night, and where folks put on their Sunday best to see larger than life tales that took them to exotic locales, onto color-splashed soundstages, or deep into city streets. They were the houses of the big Hollywood musicals, the spectacles and the epics and wide-screen Cinemascope pictures projected onto silver screens 3 storefronts wide and 2 stories high.

It was an era, from the 1930s and into the early ‘60s, when going to a movie was a national pastime, bigger than baseball. A time when over 75% of every entertainment dollar was spent at a movie house. Between the decline of radio and before television overtook every household, the oh-happy-days period between the end of World War II and before a President was gunned down in Dallas, nearly three-quarters of the U.S. population went to see a movie once a week.

And here in Memphis, there were choices a-plenty.

A glance at the newspaper theater sections in the ’40s, ‘50s and ‘60s gave readers their local neighborhood theater movie listings at the Linden Circle, the Crosstown on Cleveland, the Idlewild on Madison, the Peabody on Cooper, the Airway on Lamar. The Bristol on Summer, the Studio on Highland, the Guild on Poplar, the Park at Park and Highland, and the Memphian on Cooper and Union.

And downtown. When downtown Memphis was in its heyday, where most Memphians went for errands, went to shop, to dine, and to stroll.

Downtown had the movie palaces. The Warner and the Strand and the two Loew’s – the State and the Palace.

And then there was the Malco. And the Malco was the king.

The “palatial majesty” of the magnificent palace, as described by The Commercial Appeal upon its 1928 opening, could still show off its spacious lobby and twin staircases, its three sprawling balconies and its wide domed ceiling, its elegant gold and red décor, and its glistening crystal chandeliers. Once the home of live theater acts and old vaudeville, the velvet curtain over the proscenium now opened wide for moving pictures. And for special weekend showings and opening nights, the Mighty Wurlitzer organ rose from the orchestra pit and mesmerized adoring crowds. Just a few decades young, the grand dame was still capturing the awe of patrons young and old.

“I fell in love with the theater on my sixth birthday,” said Hillsman Wright in 2018. “It was 1958. My mom took me and I walked into the lobby of that theater, and I was transported. I had never seen anything like it. It was a wonderland for me.”

The late Vincent Astor’s memories were equally vivid when we spoke to him in 2018. “I was very very young. And I came in here and looked up – and this is very romantic – I came in here to see ‘True Grit’ in August or September of 1969 and I looked up for the first time, and in the light of the projector beam, I saw the most beautiful room I had ever seen in my life.”

The Orpheum becomes The Malco

As recounted in Part I of our series on the Hidden History of the Orpheum, the difficulties of the Cullins-Evans team in the late 1930s to obtain distribution rights to first-run motion pictures and keep up the theater’s cash-flow led to a default on their lease, returning the theater to its Bank of Commerce bondholders. As a result, the Bank of Commerce accepted a purchase proposal by rival theater owner M.A. Lightman, who bought the theatre for a mere $75,000. Mr. Lightman took over the theater by late March of 1940, and within weeks changed its name to The Malco.

And as a pledge to Memphis theater-goers, Mr. Lightman promised to “zealously” guard Memphis’s leading show palace, showing “only the best motion pictures from Hollywood’s foremost studios.”

He had reasons to be confident in his pledge, as we will reveal below. And soon after Lightman’s purchase, The Malco announced itself as the “New Malco, formerly The Orpheum,” and splashed ads all over the newspapers’ theater sections. It touted itself as “The South’s Finest Theatre,” and in the mid-1940s, began to supplement all of its summer promotions by highlighting the invention of air conditioning with its “Cool Comfort and Pure Clean Air in ‘Malco Air – Conditioned’ Theatres.”

In addition, Mr. Lightman was a leader in helping raise moneys for the war effort during World War II. Patrons could anticipate free showings on certain films with purchases of War Bonds, which turned into coordinated city-wide efforts that involved multiple theater chains.

As the gallery below shows, the period from the early 1940s into the early 1960s presented a weekly feast for movie-going, a cinematic smorgasbord for Memphians during an American era at the peak of its Hollywood influence worldwide.

A Historic Lawsuit, and the End of an Era

For M.A. Lightman after the end of the war, not everything was turning up golden statuettes.

In August of 1946, a $3 million lawsuit was filed by six independent theater owners that sought damages from M.A. Lightman, his associates, and the nation’s eight major film distributors for violations of the Sherman AntiTrust Act. The suit charged that Lightman and his associates had since the late 1930s conspired to pool their collective resources in a “circuit buying power” to control distribution and eliminate competition of “first-run” (i.e. the top studio) motion pictures to only the theaters in their so-called circuit, which in the early 1940s included The Malco and the two Loew’s theaters, among others. This control, the suit claimed, delayed the showing of these top films to other neighborhood* theaters for week after their initial runs downtown when, presumably, most theater-goers had already seen the films.

*Neighborhood theaters is not just a reference to local theaters; it is a specific reference to theaters that were independently owned. The larger downtown theaters, referred to “first run” theaters, were owned by the “Big Five” major motion picture studios under the “studio system,” whereby the studios controlled the entire production of their films, including booking their movies in their theaters. Here in Memphis, downtown’s first-run theaters were the Malco, the Loew’s State theater, the Loew’s Palace theater, the Warner, and the Strand. Studios showed their first-run studio films at one of the studio’s downtown theaters, then after a few weeks (depending on their popularity) licensed the films to independent, neighborhood theaters by granting them the right to show the film for a theatrical rental rental fee.

While the suit included six independent theater owners – including the owners of the Idlewild Theatre, the Airway, the Luciann, the Hollywood, the Bristol, and the Rosemary theaters – its filing was led by Chalmers Cullins and Nate Evans, the owners of the Orpheum Theatre in 1940 before Lightman’s purchase and before it became the Malco.

In the suit, Cullins-Evans were finally able to detail their version of their default on their 1940 Orpheum lease, and how Lightman had so easily swept in to make the purchase of the grand dame of the theatre circuit.

From The Commercial Appeal, August 23, 1946:

“At some time prior to 1937 . . . M.A. Lightman and the distributor defendants (the circuit and the studios) entered into a combination and conspiracy to drive the Orpheum Theater completely out of the motion picture business by preventing it from obtaining films from any of the distributor dependents (the studios). As a result, the Orpheum was unable to obtain any but inferior films, and such as were rejected by Lightman for showing at his theater. . . At that time, Lightman was operating what [was] the Palace Theater under the name of the Malco.”

“As a result, they (Cullins-Evans) were forced to default on upon their lease in February, 1940, at which time the Orpheum Theater was returned to the Bank of Commerce . . . and was offered by them for sale. Meanwhile, Lightman had been purchasing bonds of the Orpheum Theater at a greatly reduced rate, averaging from eight to 12 1/2 cents on the dollar.

“At the public sale of the Orpheum, M.A. Lightman bought is for the amount of $75,000 with the understanding that such of its bonds as he held could be applied to the price. He immediately changed its name to the Malco Theater and began to exhibit in it first-run pictures of all the distributor defendants, especially Paramount Pictures, Inc., and has since continued to operate it . . . as a very lucrative and profitable business. . .”

Eight months later, in April of 1947, the suit was settled: M.A. Lightman admitted no wrong-doing, and an agreement was made to split his theater business controls and part ways with the other defendant theater owners. But like any good movie, the story didn’t end there.

The lawsuit of Memphis independent theater owners vs. Lightman and associates was just one in a series of nationwide lawsuits that became a part of the U.S. Justice Department’s antitrust case asking the Supreme Court to “require five major motion picture producers, distributors and exhibitors to dispose of their local movie houses scattered throughout the country.”

The Paramount Decision

In the United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. – known as the Hollywood Antitrust Case of 1948, or, the Paramount Decision – the Supreme Court ruling barred the “Big Five” major film studios (Paramount, MGM, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO) from owning their own exhibition companies and from owning their own theaters and theater circuits around the country.

From The Commercial Appeal, January 22, 1948:

All Major Movie Houses In Memphis Affected

All of the major downtown theaters in Memphis would be involved should the Supreme Court require that the large motion picture companies dispose of local houses.

The Warner is owned by an exhibition company affiliated with Warner Bros. Pictures Inc. Loew’s State and Loew’s Palace are operated by Loew’s Inc., which owns Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures. The Malco and Strand are run by the Lightman interests, the Lightman interests operating these theaters and others in the Malco Circuit in partnership with Paramount Pictures.

The landmark decision changed the way the motion picture industry functioned, and for the next generation of filmmakers and movie-goers, brought about a booming creative, blockbuster era in film that saw advances in sound, color, technology, special effects, and new ways to tell sweeping and intimate stories. Independent movie theaters would thrive, independent producers would take more creative risks, art house theaters would crop up everywhere, and in the larger theaters, audiences would experience stories the way they had never experienced them before. Here in Memphis, the Malco would once again play a major role.

Modern Miracles – Widescreen, 3D, Cinerama, and CINEMASCOPE

To compete with the ever-increasing popularity of the new piece of transfixing furniture found in Americans’ living rooms – the almighty television – Hollywood responded by exploring ways to drag audiences away from their TVs and give movie-goers experiences they could not possibly replicate in their own homes. Simply having air-conditioned theaters was no longer enough.

From Britannica.com:

“The film industry believed that the greatest threat to its continued success was posed by television, especially in light of the [Paramount Decision] decrees. The studios seemed to be losing their control of the nation’s theatres at the same time that exhibitors were losing their audiences to television. The studios therefore attempted to diminish television’s appeal by exploiting the two obvious advantages that film enjoyed over the new medium—the size of its images and, at a time when all television broadcasting was in black and white, the ability to produce photographic color. In the 1952–53 season, the ability to produce multiple-track stereophonic sound joined this list.”

And finally, as television continued to keep audiences at home, studios widened the aspect ratio (the ratio of width to height) of the motion-picture image, which had been standardized at 1.33 to 1 since 1932.

In the early 1950s, studios unveiled films filmed in 3 dimensions – 3D – that required audience members to don the ever-iconic 3D-glasses for motion pictures like 1952’s action adventure film “Bwana Devil,” the Vincent Price mystery-horror flick “House of Wax” (1953) and the monster-horror classic “The Creature From the Black Lagoon” (1954).

Around the same time, 20th Century Fox was getting ready to unveil a method of shooting and projecting films in an ultra-widescreen format that would dominate movie screens for the next couple of decades: CinemaScope.

From American Cinematographer :

CinemaScope is a simple, inexpensive process applicable to either color or black-and-white films, which simulates three-dimension to the extent that objects and actors seem to be part of the audience, while its stereophonic sound imparts additional life-like quality as it moves with the actors across the screen.

From its panoramic screen, two and a half times as large as ordinary screens, actors seem to walk into the audience, ships appear to sail into the first rows, off-screen actors sound as though they are speaking from the wings.

Here in Memphis, CinemaScope was introduced to movie-goers with the epic film “The Robe.” And it was the Malco that outfitted their theater first, revealing in June of 1953 that “the equipment is being shipped today for installation in the Malco. The first showing of the revolutionary new screen process which has the entire film industry excited will be at an invitational preview at 10 a.m., June 11.” (Commercial Appeal) “The new CinemaScope screen here,” the article read, “will be 51 feet wide by 20 feet high, as compared to the present 23 by 18.8.”

Watch the 1953 trailer of “The Robe” here:

Then came Cinerama.

While audiences nationwide weren’t introduced to it until the early 1960s, Cinerama was introduced to the world just before CinemaScope took over the big screens. Cinerama premiered in New York in September of 1952 with the documentary-travelogue “This Is Cinerama.” Its impact on audiences and on movie-going cannot be overstated. Cinerama was an ultra wide-screen presentation of films shot with three cameras, projected onto giant, specially-constructed screens that were at least 70-feet wide (depending on the venue), curved at a 146-degree field of view that partially surrounded the audience. It enthralled film-goers – some experienced queasiness, as the size and scope of the images simulated actual movement, like today’s virtual-reality headsets – famously taking audiences onto a Long Island roller coaster ride and flying them over the American West behind the nose of a B-25 bomber.

This Is Cinerama became one of the highest-grossing films of all time during the 1950s, and it won two Academy Awards. It made its international premier in London in 1954, and then began traveling around the country, premiering in regions and theaters willing and able to adapt their theaters to accommodate the huge screen, the three-camera projection system, and the additional sound equipment. Famously, the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood was designed and built specifically to showcase the ultra-wide screen movies that would be produced in the years to come. “The Dome” opened in 1963 with the premier of the epic comedy “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.”

Here in Memphis, the Loew’s Palace took the honor in premiering “This Is Cinerama” to the Mid-South region, the only theater between Houston and Atlanta and south of Louisville to host the film. It cost an estimated $100,000 to remodel the theater for the projection system. It opened at the Loew’s to great spectacle and wide acclaim on July 27, 1961, and ran for 11 weeks before another Cinerama film, “The Seven Wonders of the World,” took its place.

Watch the 2017 restoration of the 1952 trailer for “This Is Cinerama”:

But Cinerama took its toll on the downtown theater.

As quoted from Cinema Treasures:

“It was at this time (1961) that the Wurlitzer organ was removed from the building. The installation of Cinerama required a number of interior alterations to accommodate the huge curved screen and triple projection equipment. That screen could not be used for standard format movies and, when it was removed in October 1963, the auditorium looked patched over and shabby.”

The alterations – especially as combined with Urban Renewal a decade later – would contribute to the eventually downfall of the theater, as detailed here in Creme de Memph and in Cinema Treasures.

The Malco would get its turn a year later with the arrival of a single-camera wide-screen projection system of Cinerama and the 1962 epic “How The West Was Won.”

And so it was. When the Malco premiered “How The West Was Won,” it continued its run as one of the dominant go-to places to see a movie. It came during a period of instant nostalgia from the late-1940s to 1963, that at the time seemed it would last forever but in hindsight was fleeting, as times were about to rapidly, and traumatically, change.

Up next: Integration; “Goldfinger”; the Malco becomes a target; downtown in turmoil; urban renewal; the sale of the Malco.

Sources & Credits:

- the Orpheum! Where Broadway Meets Beale, by 1980-2015 CEO Pat Halloran. Published 1997

- The Commercial Appeal archives, courtesy of ProQuest, access through the Memphis Public Library

- Cotton Row to Beale Street, by Robert A. Sigafoos. Published 1979

- Memphis and the Paradox of Place: Globalization in the American South, by Wanda Rushing. Published 2009

- DIG Memphis, the Digital Archive of the Memphis Public Libraries

- ProQuest Historical Newspapers, provided by the Memphis Public Library

- Our History, the Orpheum Theatre: About Us, History, the Orpheum Theatre.

- The archives of the Orpheum Theatre and the assistance of the Orpheum staff

- Memphis Movie Houses, by Vincent Astor and Images of America. Copyright 2013

- “Beale Street USA: Where the Blues Began” 1970, published by the Memphis Housing Authority

- “Panic at the Picture Show: Southern Movie Theatre Culture and the Struggle to Desegregate“, by Susannah Broun, Swarthmore College

- “Advanced vaudeville,” financial panic, and the dream of a world trust. 2012, Gale Academic OneFile

- the Orpheum Circuit, wikipedia.org

- CinemaTreasures.com

- 2018 interviews with Hillsman Lee Wright and Vincent Astor

- ProQuest Historical Newspapers, provided by the Memphis Public Library

Thank you, Mark Fleischer. What a fascinating and in-depth – very in-depth – story of film exhibition, movies and the many theatres where patrons could see them during the heyday of movie-going. Even in the depths of the Great Depression 60-80 million people attended the movies each week, a trend that continued till 1945. Marcus Loew famously said, “We sell tickets to theatres, not movies.” The history of M.A. Lightman was of special interest to me. Again, you’ve added another chapter recounting the up and down history of the Orpheum/Malco/Orpheum. Here’s hoping your research will result in a book.

Delightful article. Although I am sure that my parents took me to the Malco as a small child on those special trips which going “downtown” constituted, my most vivid memories of the Malco are two. First, while in high school, several friends and I sneaked into the balcony of the theater, entering by the alley fire escape door which was opened by the only one of us who paid for admission. The movie was “Guys and Dolls.” The other memory was of the long lines waiting to see “Goldfinger,” the great James Bond film.

Robert Lanier