“Don’t Tear Down the Malco!” Urban renewal threats spark looks back at a rich history

Urban renewal had crept its way to Beale Street. At least on paper. In the summer of 1963, Beale Street, its surrounding neighborhoods, and large swaths of block after block in the immediate area were in the crosshairs for federally-funded renewal programs, as city officials and the Memphis Housing Authority (MHA) unveiled “an exciting plan to restore Beale Street to its historic splendor.”

Of course, according to the urban renewal playbook, restoration would first be put into action behind the controls of a bulldozer. And with millions of federal dollars available to local officials to condemn, purchase, and demolish select properties under a variety of conditions 1, massive land clearance was on its way.

1 Under Federal regulations, in order for an area to qualify for urban renewal, more than 50% of the structures in a project area must be considered “sub-standard” in condition. The Memphis Housing Authority determined demolition of structures based on three broad criteria: 1) Does the building meet minimum safety and health standards? 2) Does the building physically block installation of improvements the lack of which helped created the substandard area, such as adequate streets, drainage and sanitary sewer facilities? And 3) will the continued existence of the building deter redevelopment of the area?

Included in the almost two-dozen blocks of the Beale Street Phase I Urban Renewal Project area, land clearance was proposed for the block at the southwest corner of Linden Avenue between Front and Main streets; Beale and Second, which included Lansky Brothers Men’s Shop; and the east blocks of Main and Beale. There, on the northeast corner, was a loan and jewelry store, and Toney’s Fruit Stand. On the southeast corner stood the six-story, all-masonry M&M/Randolph building, built in 1891, which at street level housed a shoe store and the Blue Light Studio along Beale, and a Pantaze drug store along Main.

The proposed renewal plans did not stop at Beale; they extended past the shadows of the marquee and through the lobby of the grand theatre palace on South Main at Beale. The once and current Orpheum Theatre – known from 1940 to 1976 as The Malco – was by the end of the year nineteen hundred and sixty-four penciled in as one of the proposed locations for a new downtown administration building for Memphis Light, Gas & Water.

Talks of tearing down the great theatre sparked public outcries. The opinion pages of the local newspapers the Commercial Appeal and the Press-Scimitar were filled with letters and editorials in pleas to save the Malco. Within days and continuing into early 1965, memories of the great movie palace filled hearts and minds.

Origins: From Stage to Screen, 1890 to 1940

From books to articles to the Orpheum’s own website, the history of Memphis’s last grand theatre palace is well-chronicled.

In his definitive book on the subject, Memphis Movie Houses, the late Vincent Astor – and longtime Orpheum resident expert and entertainer – declared in his introduction that, as a town at a crossroads of river and railroads, “Memphis has always been a theatrical town. A troupe of comedians performed in a private home as early as 1829, just 10 years after Memphis’s founding. Theatre listings can be found in the earliest city directories and newspapers list theatrical performances throughout the entire history of Memphis.”

The Grand Opera House

Today’s building was not the first structure to occupy the historic corner of Main and Beal (as it was sometimes spelled in the 1800s). That distinction belongs to the William McKeon Home, built about 1838 and demolished in 1852, “to make way for the C.B. Bryan and Son Coal Yard” (according to “Beale Street USA,” a 1970 study published by the Memphis Housing Authority). Financed by a group of 25 stockholders led by W.D. Bethell, the coal yard was cleared in 1889 to provide a site for the Grand Opera House.

Wrote columnist Mimi White for the Commercial Appeal in 1973:

Memphis had one theater at the time, the New Memphis Theater on Jefferson, east of Third, owned by Lou Leubrie . . . Memphis was more than ready for a theater of noble proportions on October 29, 1889, the day of the laying of the cornerstone of the Grand Opera House. She was not even a city then, having bungled her affairs so badly that she lost her charter. But the sights of the 25 stockholders were set not on the painful failures of the past, but, Mr. Menken* said, “on the growing importance of Memphis as the future city of the South.” He told a reporter, “When it’s completed it will be seen that the city’s growth has been anticipated by 20 years.”

*J.S. Menken, chairman of the Grand Opera House building committee

As described in the 1997 book (by 1980-2015 Orpheum CEO Pat Halloran) the Orpheum! Where Broadway Meets Beale, the Grand was lavishly adorned, could seat over 2,000 patrons and boasted a stage that was reported to be the largest of any theatre outside of New York City. The Grand Opera House was unveiled to adoring guests of high-society Memphis in September that year with an opening act of Miss Emma Juch and her Grand English Opera Company. Memphis theatre-man Frank Grey served as the theatre’s first manager.

From 1892 to 1906, the Grand faced a rapidly changing world, with exponential growth of U.S. industry during the Second Industrial Revolution, the growth of the super-wealthy during the Gilded Age, the Spanish-American War, and yet another yellow fever outbreak. With these challenges came evolutions in audience appetites. Despite all that and changes in management, the Grand would go on to stage operas, plays, comedies, and minstrel shows. In 1899, Colonel John d. Hopkin took over ownership – renaming it Hopkins Grand Opera House – and immediately made changes to the theatre’s décor and switched the Grand’s format to the light, farcical entertainment known as vaudeville, which featured acrobats, magicians, comedians, burlesque, trained animals, jugglers, singers, and dancers. From 1902 to 1907, Col. Hopkins adopted a more highbrow type of vaudeville entertainment that was advertised as “Advanced Vaudeville.”

The Original Orpheum

In 1907, Col. Hopkins turned over his management to the Orpheum Circuit, a group that since the 1890s had grown a network of theatres nationwide that hosted traveling troupes of vaudeville performers. With the deal, the group changed the name of the Grand Opera House to The Orpheum.

Orpheum: What’s in a name?

Orpheum theatres are named in honor of Greek mythology and the story of a musician named Orpheus, who falls in love and marries a nymph named Eurydice and, after she dies from a snake bite, follows her into hell intent on bringing her back from the underworld. The original Orpheum theatre was in San Francisco, which opened as the Orpheum Opera House in 1887 by a vaudeville star named Gustav Walter. Walter, with the backing of Morris Meyerfield, expanded operations and attracted vaudeville talent to their theatre by giving them opportunities to perform in leased theatres in other cities.

After the sudden passing of Walter in 1898, Meyerfield partnered with Martin Lehman in Los Angeles and the group hired vaudeville booking agent Martin Beck to expand their bookings across the country. The group leased or made financial deals with opera houses in large cities across the Midwest and the South – usually those connected by the growth of the railroad, which allowed vaudeville to thrive. As part of these deals, they renamed these theatres and opera houses under the Orpheum brand, establishing a circuit of shows and performers that would travel across the country through their network of Orpheum theatres. Other groups and investors joined in, and eventually the Orpheum Circuit included more than 60 theatres. Today there are about 20 Orpheum theatres remaining across the country.

In 1917, the moving picture arrived, the same year the United States declared war on Germany for the First World War. A couple years into the war the Orpheum was featuring motion picture newsreels of weekly events and cartoons to go along with its vaudeville performances. Among many famous performers of the day, “The World’s Greatest Actress” – Madam Sarah Bernhardt – appeared on stage late in her storied career; Helen Keller and her assistant appeared weekly, demonstrating her unique methods of communication; and Harry Houdini would perform his death-defying escape acts on stage.

Despite these attractions, into the early 1920s vaudeville struggled to compete, not only with moving pictures, but also with the advent of a new medium called radio. The Orpheum grasped onto the new medium and filled bookings and the house with patrons who listened to live radio performances.

And on the evening of October 16, 1923, 30 minutes after a performance of Miss Syncopation, starring Blossom Seeley and Bennie Fields, night watchman Charley Toler noticed “a thin blaze of flame spurt upward in one of the rooms on the third floor occupied by the Tri-State Manufacturing Co., manufacturers of women’s garments.” The manufacturer women’s garments and aprons had rented the second, third, and fourth floors in the office spaces facing Main Street. Speculation was that the fire had started in a workshop sewing room “on the Beale Avenue side of the building.”

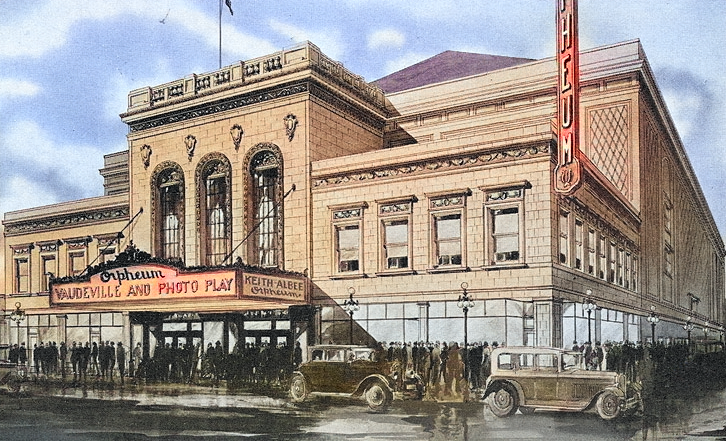

Within weeks of the devastating fire, both city leadership as well as the Orpheum Circuit were determined to rebuild the Orpheum. Investors came together, and a new theatre was financed by the Orpheum Circuit and members of the local Memphis Theatre and Realty Company. Construction began by October of 1927. It was designed by the renowned theatre architectural firm C.W. and George Rapp of Chicago, and its design was inspired by the Orpheum in Omaha, Nebraska, which broke ground in 1926 and opened in October of 1927.

The New Orpheum

The New Orpheum theatre opened to great fanfare and even greater opulence on November 19, 1928. The newly crowned “Monument to the Spirit of Memphis!” (as announced by the Memphis Theater and Realty Company), the theatre could boast 5000 yards of “luxurious carpeting,” almost 3000 comfortable, leather-covered seats, “crystal bead twinkling lights,” a “gold-tinted dome” overhead, “bathed” purified air for the hot summer months, silk and satin drapes, and the ever-spectacular, always moving, and timelessly magical: the Mighty Wurlitzer Organ.

Listen to our StoryBoard 30 featuring the late Vincent Astor talk about – and play! – the Mighty Wurlitzer Organ.

The description of the opening evening, penned by the Commercial Appeal’s newsman W.H.A., was adoring and lyrical:

“Last night it was packed from pit to the highest balcony. Society in evening clothes occupied the boxes and sprinkled itself in the orchestra circle. There it brushed elbows with the great middle class of the city. Against the background of pearl and gold and white this cosmopolitan gathering was clearly outlined. They had come for the most part in an eagerly reverent mood, they gave vent to their admiration, at the chaste elegance of the surroundings and they manifested with abundance an applause their enjoyment of the opening bill. . . There was an undercurrent of feeling that something more than festivities were involved. It was another bit of town history being enacted when the organ was elevated above the floor and the guest organist inaugurated the ceremonials with a solo number.”

Trouble Ahead

The excitement of the theatre’s opening was soon met with bad luck and rough going into the 1930s, with the decline of vaudeville, the onset of the Great Depression, the rise and fall of the minstrel shows and live “flesh” shows – less than wholesome entertainment featuring scantily clad women – and by the rise of the moving picture shows.

As recorded in the book the Orpheum! Where Broadway Meets Beale, changes in management were frequent in the 1930s during the depression years and with the adjustments to new formats, audience tastes, and audience dollars.

Two major theatrical groups, the Keith-Albee Circuit and the Orpheum Circuit, combined with the F.B.O. Picture Company – another merger begat Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO) – to allow vaudeville theatres “to obtain first-run pictures and broadcast radio live.” This format of live shows and picture shows lasted until February 1933, when the group declared bankruptcy. In July of that year, the G.S.C. Theatre Circuit of Chicago brought continuous motion pictures to the theatre. The Chicago group gave way to a man and a name that would figure rather prominently in the decades to come, M.A. Lightman, who leased the theatre for 2 years starting in December of 1934. (Lightman closed the theatre after just 11 months due to a dispute with a theatre union, but opened the theatre in April of ’36 for the Red Cross and a fundraiser to help Tupelo recover from a tornado*).

After Lightman’s lease ended in December of 1936, Tri-State Transit Company, run by W. H. Johnson out of Shreveport, Louisiana, leased the theatre. In 1937, Orpheum alum Chalmers Cullins ran the theatre under the operations of Tri-State Amusement with the backing of Bluff City Amusement Company.

*This is a correction and clarification from the Orpheum Theatre and with the support of the Orpheum’s archival records.

Also in 1937, under the new management, an ad for the Orpheum announced new pricing for Black, “Colored” patrons.1 Called the “Colored Balcony” in the ads of the time, the segregated balcony was advertised as the only of its kind for the combination of stage and screen performances (this is misleading; other downtown theaters likely had separate seating for Black patrons for moving picture shows – the Pantages Theatre (later the Warner Theatre) had a separate “Colored Entrance” in the alley to the right of its entrance at 52 South Main). Ads being what they are, these ads presumably took advantage of the theatre’s prominence on Beale Street and to boost ticket sales. Ticket prices were offered at a significant discount for “any seat, any time.” 2

Black patrons were directed to use the existing side entrance along the Beale Street side, and true to Jim Crow segregation, with seating only in a cordoned off section of the balcony. These balconies had nicknames like the “pigeon roost,” were later referred to Jim Crow balconies, and balcony audiences were sometimes referred to as “the peanut gallery.”

1 References to balconies, or galleries, set aside for Black, “Colored” patrons, are reported as early as the opening weeks of the original Grand Opera, in October of 1890. A Memphis Appeal-Avalanche* article refers specifically to a “reserved department of the colored gallery.” During the Jim Crow era, reporting and advertising for segregated seating was at times vague, displayed in small print, or not mentioned at all. Mainstream newspapers, knowing their readership was predominantly white, catered to white patrons and emphasized the exclusive amenities offered to them. *The Memphis Appeal-Avalanche was the union of Memphis newspapers the Memphis Appeal (started in 1886) and the Memphis Daily Avalanche (1866-1885)

2 An early version of this article quoted a claim that 1937 marked the first such balcony of its kind. With the assistance of the Orpheum’s management and archival resources, we acknowledge the oversight in our initial drafts. How segregated seating was handled by theaters and the press is fascinating, at times contradictory, and by today’s standards, shameful; these complexities make for interesting narratives, and beg for a more in-depth look, which we will address in the next installment of this series.

In Memphis Movie Houses, Vincent Astor relays this story about the colored balcony at the original Orpheum:

“A story told by Chalmers Cullins, an Orpheum employee (and later, a lease-holder), relates that Julia Hooks, a pioneer civil rights activist, refused to sit in the ‘colored’ balcony during one of Sarah Bernhardt’s performances. She was finally sold an orchestra seat.”

Black entertainers were also booked. The Mills Brothers performed during the 1939-40 season, and some of the great jazz artists of the day brought their bop and brass to the Orpheum stage, including Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong.

However, motion picture showings, newsreels and cartoons, brief vaudeville revivals and top-notch live entertainment were not enough to sustain the theatre’s survival. In particular, the operating team of Chalmers Cullins and Nate Evans were facing challenges obtaining distribution rights to first-run motion pictures, losing “quality movies” to rival theaters like the Loew’s State, the Warner, and the original Malco Palace (the Loew’s Palace, on Union).

“It was hard to believe that the Orpheum couldn’t be kept afloat,” wrote Pat Halloran in the Orpheum! Where Broadway Meets Beale. “Since the reopening in 1928, nothing seemed to go right for this majestic theatre.”

Turns out, there were other underlying reasons for the theater’s struggles and ability to obtain first-run movies, as would be publicly revealed after the Second World War (and that we will reveal in the next installment).

M.A. Lightman steps in

As a result of their difficulties, the Cullins-Evans team defaulted on their lease and returned the theater to its bondholders under the trustee the Bank of Commerce. In short order, the bondholders accepted a proposal by rival theater owner M.A. Lightman, who bought the theatre for a tidy sum of $75,000. Mr. Lightman permitted the remaining scheduled early 1940 live acts and motion picture showings to keep their bookings, and by late March of 1940, the theatre was turned over to him.

There were two remaining issues: his company was already leasing a theatre owned by Loew’s, called the Malco Palace, on Union Avenue; and, he wasn’t sure how to name his new acquisition on Main and Beale. “We may call it the Malco Orpheum, combining our company name with the one the theater has borne since it was built,” Mr. Lightman said to the Commercial Appeal. “We might simply call it the Malco. We could call it the Paramount for the national organization which will be our partners in this operation. Or we might simply stick to ‘The Orpheum.’”

Within days, he decided, the five-year lease with Loew’s would not be renewed, and the Malco Palace would be turned back to over Loew’s – it remained the Loew’s Palace Theatre until 1977. Meanwhile, “we are going ahead with the preparations,” said Mr. Lightman. “The house is being given a general cleaning with new upholstering for the seats and furniture and repairs to the equipment.”

And the name? Lightman solicited public input for a few days before giving the theatre its new name under the M.A. Lightman Company name. It would be called “The Malco.”

Next Installment, Part II: The MALCO Years, the Battle with MHA & LG&W, and Urban Renewal

In a summer-long series in honor of its 95th birthday, StoryBoard revisits an era when Memphis almost lost its last great theatre palace: its struggles and survival during mid-1960s urban renewal in a ravaged downtown; and its pivotal 5-year revival from 1976-1980. Read our Introduction here>>

Don’t miss these feature stories, Planning & Development news, and upcoming local happening in Arts & Culture. Sign up for our FRIDAY WEEKEND READS NEWSLETTER to receive our Weekend Reads, upcoming Arts & Community events and happenings, and for the latest on StoryBoard Shorts Doc Fest

Sign Up Here!

Sources & Credits:

- the Orpheum! Where Broadway Meets Beale, by 1980-2015 CEO Pat Halloran. Published 1997

- The Commercial Appeal archives, courtesy of ProQuest, access through the Memphis Public Library

- Cotton Row to Beale Street, by Robert A. Sigafoos. Published 1979

- Memphis and the Paradox of Place: Globalization in the American South, by Wanda Rushing. Published 2009

- DIG Memphis, the Digital Archive of the Memphis Public Libraries

- Our History, the Orpheum Theatre: About Us, History, the Orpheum Theatre.

- The archives of the Orpheum Theatre and the assistance of the Orpheum staff

- Memphis Movie Houses, by Vincent Astor and Images of America. Copyright 2013

- “Beale Street USA: Where the Blues Began” 1970, published by the Memphis Housing Authority

- “Panic at the Picture Show: Southern Movie Theatre Culture and the Struggle to Desegregate“, by Susannah Broun, Swarthmore College

- “Advanced vaudeville,” financial panic, and the dream of a world trust. 2012, Gale Academic OneFile

- the Orpheum Circuit, wikipedia.org