FROM THE ARCHIVES: Originally published in the print edition of StoryBoard Memphis in April, 2019 as part of our “Newman to Now” series; it has been expanded for the online edition.

The Newman to Now project looks at the forces that have led to differing fates of several Memphis buildings and districts. The Mid-South Coliseum is an ideal case study for examining these forces and, particularly, the role citizen groups can play determining outcomes at these sites.

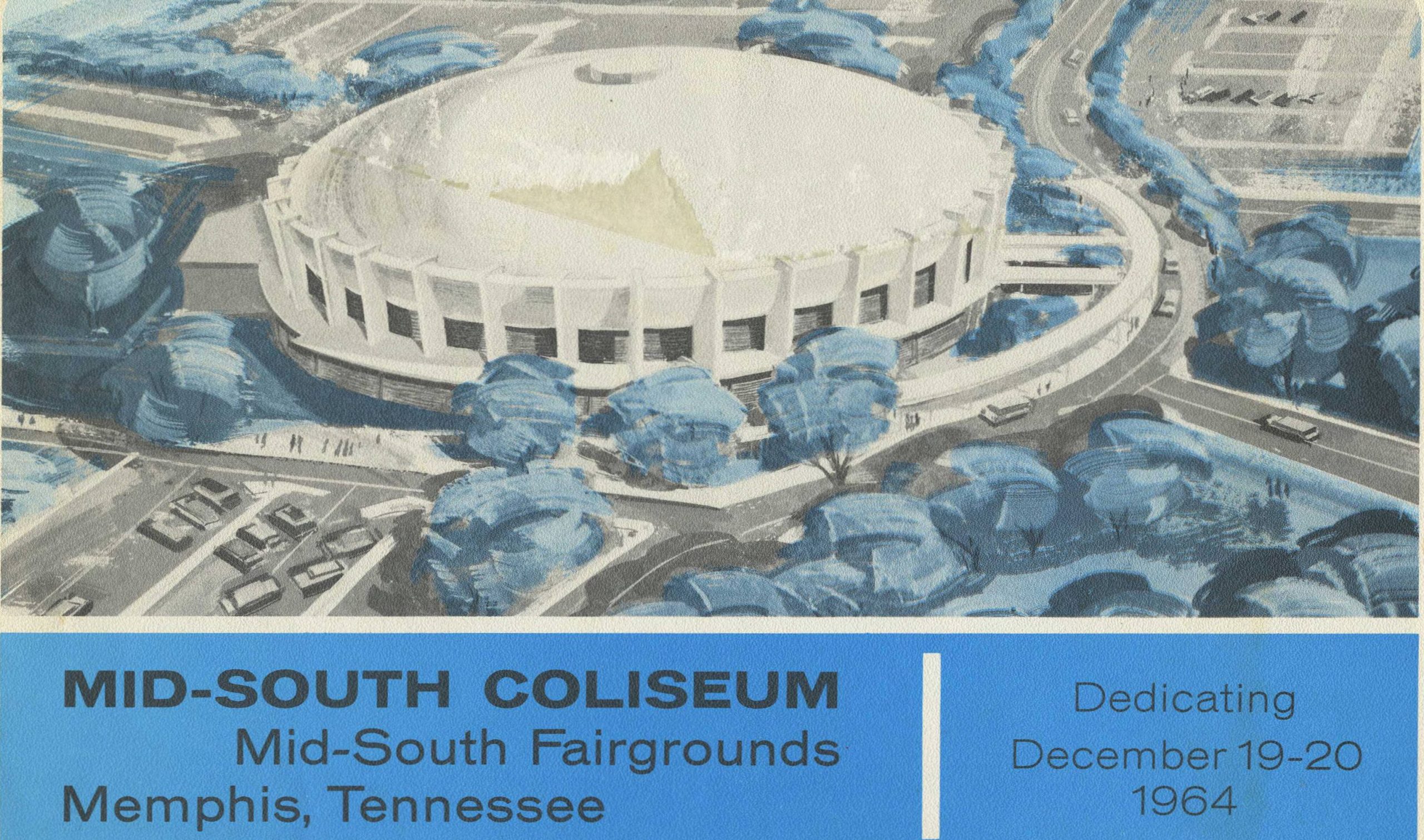

The Mid-South Coliseum is a mid-century modern, 10,000-seat arena located on the historic Mid-South Fairgrounds. It was completed in 1964 by the City of Memphis and Shelby County for $4.7 million. According to dedication brochure, the Coliseum was “Constructed by the people of Memphis and Shelby County for athletic, cultural and entertainment benefit of the entire Mid-South Area.” The Liberty Bowl, which is a football stadium also located on the fairgrounds, was built at around the same time. These structures reflect the importance of civic pride and sports in Memphis during the 1960s.

Don Newman photographed the Coliseum both during construction and during its early operation. This was a time when the Coliseum truly reflected the culture of the city. It figured prominently in both the civil rights and music history of the city. In recognition of its historical importance, the Mid-South Coliseum was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2000.

NEWMAN-COLISEUM-CONSTRUCTIONAbove: Don Newman captured the Mid-South Coliseum from the air during construction in 1963 (used by permission; any other use is strictly prohibited. See https://www.memphisheritage.org/newmans-memphis/)

Above images courtesy Memphis and Shelby County Room, Memphis Public Library & Information Center.

The Coliseum was the first auditorium in Memphis planned as an integrated facility and the first major structure in the region built without segregated entrances or bathrooms. Performances before integrated audiences began as soon as the Coliseum opened. Interestingly, there seems to have been little to no controversy about the integrated nature of the Coliseum.

The Coliseum is well known for hosting nationally and internationally prominent performers, serving as the venue for hundreds of music acts between 1964 and 2006, including among others the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, The Police, Prince, and Rod Stewart. It hosted the concerts of Michael Jackson, Dolly Parton, Lawrence Welk, Frank Sinatra, and Crosby, Stills and Nash. It was the site of numerous performances by Elvis Presley in the later years of his concert tours in the mid-1970s, and was scheduled as part of his last tour in 1977 before his death in August of that year. Locally, it was central to the WDIA/Stax era of Memphis music history, as it hosted the WDIA Soul Review and numerous performances by Stax artists, including memorable performances by Rufus Thomas, Little Milton, and Ann Peebles.

Sports, especially the locally-beloved sports of wrestling and basketball, also found a home in the Coliseum. The Coliseum headlined numerous wrestling professional matches, including many that featured Memphian Jerry “The King” Lawler as well as other professional wrestlers. It was the site of the famous – or infamous – wrestling match between comedian Andy Kaufman and Lawler in 1982. Wrestling was so successful at the Coliseum that, for a time, wrestling events alone paid for the facility’s operating expenses.

It hosted minor league hockey, most notably as the home of the Memphis Wings and the Memphis RiverKings of the Central Professional Hockey League. And it was home to indoor soccer – the short-lived Memphis Rogues of the North American Soccer League. The Coliseum hosted championship games for basketball’s ABA (American Basketball Association), and of course, it served memorably as home court for the Memphis State Tigers.

With the breadth and frequency of events hosted at the Coliseum, it was once dubbed “the Entertainment Capital of the Mid-South.”

But it wasn’t just for sports and entertainment. It was notable as the site of the 1991 African American People’s Convention, which transformed Memphis for years to come and played a significant role in the election of Dr. Willie W. Herenton, Memphis’s first Black mayor. And, it was the site of countless high school and college graduations.

The Coliseum remained successful and popular through the 1970s and 80s. In the mid-1980s, there was even discussion of expanding the Coliseum, although these plans were never carried through. Ultimately, the City and County built a new arena, the Memphis Pyramid, downtown, and this facility opened in 1991. It is around that time that the Coliseum entered a period of decline.

The opening of the Pyramid and the subsequent move of the Tigers to the new arena certainly contributed to the Coliseum’s decline. This was further exacerbated when the FedEx Forum opened in 2004 as the home of a professional basketball team as well as the Memphis Tigers. This arena also became the city’s premiere venue for major concerts and performances. In another contributing factor, a misunderstanding led to wrestling being banned from the Coliseum. Nonetheless, the Coliseum continued as a music venue until it closed in 2007.

Two major issues ultimately led to the closure of the Coliseum after the 2006 season. The Coliseum was operating at a loss at that time, and Shelby County refused to pay its 40% share of funding after 2006. At that point, Memphis also made the decision to stop funding and to close the building. Additionally, the City of Memphis had been sued for operating several buildings, including the Coliseum, that were not ADA compliant. The federal government ordered the City to either bring these buildings into ADA compliance or cease operating them. In the case of the Coliseum, the city chose to close the building rather than make the needed renovations.

There was not an immediate citizen outcry at the time the Coliseum closed. Most people assumed that the city would eventually reopen the building. However, the City argued that renovating the building would be prohibitively expensive and put forth plans for its demolition. In 2010, a group known as Save the Coliseum formed and facilitated the initial dialogue between concerned citizens and the City of Memphis. In 2015, the City of Memphis began to actively pursue funding to redevelop the Mid-South Fairgrounds, and this was to include funds to demolish the Coliseum. This specific effort to raze the Coliseum spurred the development of the Coliseum Coalition, which drew together a variety of individuals and organizations with an interest in saving the building.

Charles “Chooch” Pickard, AIA, is the Vice President of the Coliseum Coalition. Mr. Pickard describes some of the reasons he feels strongly about saving and reopening the Coliseum:

“I think one of the misperceptions of people about our group is that we’re doing this for nostalgic reasons, and nostalgia has absolutely nothing to do with it for most of us. I believe in the fiscal responsibility of the city to not tear down something that’s in good shape… I live in Memphis because of its authenticity. It’s what keeps me here and keeps me excited about this city. And that building is the epitome of authenticity for Memphis when it comes to architecture, sports, music, civic pride. That building has it all – it says Memphis. That’s overall why I think most of us want to save it. The nostalgia is kind of icing on the cake… When we reopen it, we hope to use that nostalgia to actually help keep the building open 365 days a year. We’re really missing out on opportunities to have more tourism-related things there that could be open for tourists and the public between major events.”

The 2018 TDZ application that was ultimately approved explicitly states, “The Mid-South Coliseum and other historic buildings are preserved rather than demolished.”

The immediate goal of Save the Midsouth Coliseum and the Coliseum Coalition was to prevent the demolition of the Coliseum. This goal was achieved in 2017, when the City agreed to “mothball” the building. The preservation of the Coliseum was confirmed in November 2018 when the State Building Commission approved the City of Memphis’ Tourism Development Zone (TDZ) application for the redevelopment of the Fairgrounds as a Youth Sports Complex. A TDZ is a funding program for tourism attractions in a specific “zone” for which a baseline tax revenue is determined. Once a TDZ is enacted, the increase in the tax revenue from the new / improved tourist attractions can be used to pay for the debt incurred to build the attractions. The application that was ultimately approved, explicitly states, “The Mid-South Coliseum and other historic buildings are preserved rather than demolished.”

Now that demolition of the Coliseum has been prevented, the Coalition is working to reopen the Coliseum in some capacity. Ideally, it would open as a mid-sized, multi-use venue. The Coalition has worked to not only establish the popular and political case for its reopening, but also the legal, financial, and architectural case. In fact, the Coalition has even developed a specific plan to revitalize the space in a way that is modern, accessible, and multi-purpose.

According to Mr. Pickard, reopening the Coliseum would have significant benefits for the surrounding neighborhoods. He believes that reopening that events held at the building and the Coliseum’s potential as a tourism draw will lead to increased patronization of area businesses.

There are a few issues that have been viewed as obstacles to reopening the building. The first issue is the need to renovate the building and bring it up to ADA compliance. This has been viewed since the time the building closed as prohibitively expensive. However, the building is in excellent structural condition, and the Coliseum Coalition believes that their plan can be executed in a cost-effective way, and estimates that it would cost about $25 million to reopen the building, which is a relatively modest investment, especially considering the fact that demolition would have cost between $8 and $10 million (2018 estimates).

A second, often-cited issue is a non-compete agreement between Memphis and the Grizzlies organization. This agreement, which is meant to ensure the success of the FedEx Forum, limits the ways in which city-funded venues can be used. As an existing rather than a new venue, the Coliseum is not subject to all of the terms of this agreement. The agreement does, however, give the FedEx Forum the right of first refusal for certain categories of events, including nationally-televised and nationally touring events. Nonetheless, the Coliseum Coalition believes that the Coliseum could coexist with the Forum and its non-compete agreement, especially since it would target events of a different scale, including those with a community focus.

The Coliseum Coalition has worked alongside rather than against the City of Memphis, resulting in a great deal of trust between the two entities. This has allowed the Coalition to bring business and civic leaders, as well as journalists and other “influencers” into the building to demonstrate its structural soundness and spur interest and ideas for its redevelopment.

Save the Coliseum and the Coliseum Coalition have also brought the larger public to the Coliseum. In order to raise public interest in and excitement about the Coliseum, Save the Coliseum and the Coliseum Coalition has put on a series of annual “previtalization” events called Roundhouse Revival. Previtalization is the temporary activation of an inactive or underutilized space. This is a tactic that has been highly successful at other Memphis sites, including the Crosstown Concourse and the Tennessee Brewery. Since 2015, thousands of Memphians have attended the annual Roundhouse Revival (4,500 people attended the first event), on the grounds outside of the Coliseum.

These events feature the three core “brands” of the Coliseum: music, wrestling, and basketball. Mr. Pickard describes the energy of the Roundhouse Revival events:

“It’s really a great experience for some people to experience different aspects of the building… I grew up thinking wrestling was silly. (With apologies to purists) I never understood why people thought it was real and I didn’t understand the entertainment value back in the ‘80s when I learned about wrestling. Not until the Roundhouse Revival when we saw Bill Dundee and Jerry Lawler fighting the Coliseum Crushers, did it occur to me what that entertainment value was. But to see the power of the crowd and the excitement and the fun that was being had even though it was silly and scripted was something incredible and just that energy that was created there was something that I’d never experienced before. It’s that kind of thing and that kind of energy is what will get people pumped up about saving the building and reopening it.”

Don Newman photographed the Mid-South Coliseum at a time when the building represented civic pride and hopes for Memphis’ future. At least for now, the Coliseum will remain standing and “moth balled.” This iconic building has been central to Memphis’ history and culture. Its present speaks to the power citizen groups can have in shaping the fate of the city’s historic sites. The citizens of Memphis will decide if the Coliseum has a place in the city’s future.

Originally published in the print edition of StoryBoard Memphis in April, 2019 as part of our “Newman to Now” series, created and curated by author Emily Cohen for Memphis Heritage in 2018-2019: https://www.memphisheritage.org/newmans-memphis/

The Newman to Now project was partially funded by Humanities Tennessee, an independent affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

It’s worth remembering that it was also the site of the 1991 People’s Convention that transformed Memphis politics, leading to the election of the city’s first African American mayor, Willie W. Herenton.

Thanks Tom. I updated the story to include the convention and other memorable events.

I remember the Blast off at the Dome in 1998. I never actually been, but watched a highlight video about it! 🙂