This article originally appeared in Volume I, Issue II of StoryBoard Memphis Quarterly in March 2022.

Many aspects of our lives escape our awareness when they are working; plumbing, street paving, 5G internet connections,etc. When those same features are malfunctioning, we notice, with increasing urgency, how critical to our comfort they are.

The same is true with our bodies, though with much higher stakes. When our systems are working in concert, we do not focus on blood flowing or knees bending or nerves reacting. The remarkableness of our interconnected functions is held in the background while we focus on pressing matters – until something goes awry and our focus snaps to the parts that are not doing what they should.

As a young, healthy woman with no chronic physical medical conditions, I had an indistinct notion that kidneys are important, vaguely bean shaped, and come in pairs. That’s likely where my awareness would be still, if not for a conversation over lunch in April 2019. The previous evening, my friend George wrote a very personal social media post. He was under doctor’s orders to share that he has polycystic kidney disease (PKD), a chronic, hereditary illness with no treatment or cure. He let his network know that he would need a new-to-him kidney in the coming months and that a large percentage of organ transplants come from living donors. He ended by asking us readers to give some thought to donation.

George isn’t one for sharing medical details, which itself was enough to get my attention. That day at lunch, my colleagues’ normally boisterous conversation was more subdued, with lots of questions about PKD. The only question I could think to ask was about his blood type.

He’s B. I’m O negative.

He told me donors and recipients don’t necessarily need to be the same blood type, and we went back to conversation as usual. That exchange and his post stuck with me in a way I was not expecting. We have known each other for a long time. We worked together, we share recipes, we know each other’s families, we enjoy burning things, we make fun of each other, he’s made me confront my fear of heights on multiple occasions, I gave him the jalapeños from my garden that are, frankly, too hot for reasonable people to consume. We’re friends.

My small decisions started with resolving to learn more. I periodically read about kidneys: what they do, how transplants work, the success rate, the consequences of donation. Computer algorithms began to offer me insights about nephrology even when I was not actively searching. Along the way, a thought stitched itself into the back of my consciousness. Could I really donate a kidney?

I agonize over small decisions. I cannot walk down greeting card aisles without reading each one; I stare at canned tomatoes for minutes agonizing over the salt content. Yet, for the big things — who to share a life with, what house to buy, when to voluntarily remove an organ — I decide with my instincts first and my logic later. As I spent months in quiet contemplation,

a small, determined voice began to answer back. Yes, I could. But more importantly, yes, I should. It seemed so simple. I had two kidneys, and I only needed one. I waited for it to get more complicated, for my anxiety to kick in and tell me all the reasons why it was a bad idea, but it never happened.

While I thought, the world changed, and George got sicker. PKD doesn’t pause for pandemics, and in May 2020, George’s numbers were so low, the doctors told him it was time for a transplant. I reached the point where internet searches and inner dialogue could no longer suffice, and I turned to Greg, my trusted partner in all things. I finally said aloud what I had whispered in my heart: I wanted to get tested because I wanted to be a donor. Greg told me he believed in me, understood my reasoning, and supported my choice.

Apart from Greg, who would need to take care of me and our children while I recovered, I sought no one else’s consent. It was a decision at once selfless and self-centered in the truest definitions of the words. I thought of George, I thought of myself, and I called Michelle at the transplant clinic to be tested.

In early June, I met with the transplant team at Methodist Transplant Institute. At that first meeting, they repeatedly asked if I was there voluntarily, what I would get out of the donation, did I understand how the surgery worked, and why did I want to do this?

Yes; my friend would live. And, yes; my friend would live.

Satisfied with my answers, they sent me on to the phlebotomist for my blood sample and then home to wait.

Here’s what I thought would happen. I would be one of several potential donors who got tested. I wouldn’t be a match, but I would be a candidate for surgery so I’d go into a donor chain pool. In a donor chain, you donate a kidney to someone other than your intended recipient, who in turn gets a kidney from another recipient’s pool. If none of George’s other potential donors matched, I could get the call that I matched someone in a donor chain. I would still donate, but it would take a while to get to that point.

Instead, on July 3, the donor coordinator called to inform me that I was a direct match. It was not the call I was expecting; it was better. I knew in my soul that I was doing it. I called Greg, I called George, and I didn’t stop smiling the entire time. Two weeks, and a couple of nerve-wracking waits later, I passed a battery of physical tests to clear me for surgery and got to tell George face to face that he could have my kidney.

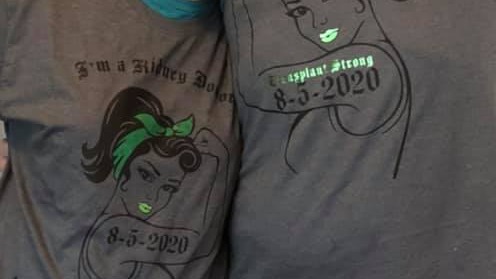

We got re-matched, did more pre-op, got COVID-19 tests, and made it to 5AM Wednesday, August 5–two months after I called to say I wanted to be tested. The process was, in turns, incredibly fast and excruciatingly slow. But it always felt like the right thing to do.

Recovery took time, but I have never doubted my decision. At 18-months post-op, my pain is gone unless I push directly on my scar. I feel great, and few things have changed except that I can only take Tylenol for pain relief and I have an even better friend.

And George? I’ve watched my former kidney lead an exciting life of marathon running and century bike riding. There’s immense joy in being part of his story.

There are thousands of people waiting for a kidney. If a small voice inside you is asking if you could be a living organ donor, let yourself explore the answer. I’m the same person I was before surgery but with one fewer kidney and a deeper understanding of myself. There is immense joy in that too.

Caroline Mitchell Carrico is a native Memphian and, as a historian by training, she enjoys researching the city’s past and pulling it into the present. When she isn’t reading and writing, she can often be found cheering on her kids’ soccer teams.