“I’d have given a year’s pay to have been able to have taken Lea’s trip into Holland and to have entered the castle of Count Bentinck without invitation.” ~General Pershing, in 1919

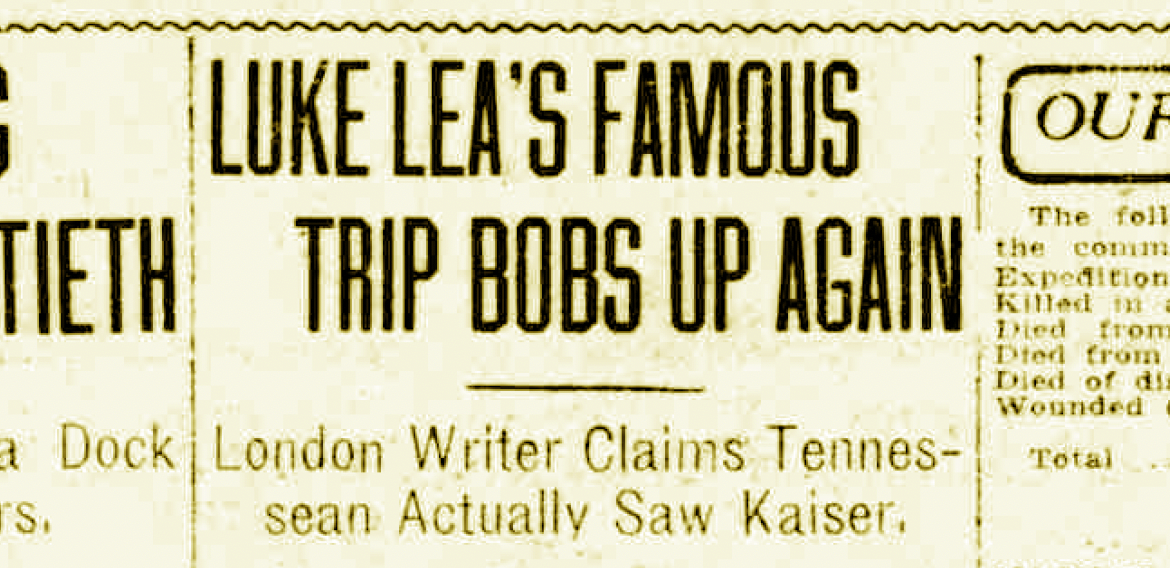

By Robert A. Lanier

Historians are still debating the degree of blame to place on the German emperor, or “Kaiser,” Wilhelm II, for starting the First World War. It is clear from the records that he understood and feared the consequences of a European war. Nevertheless, as the head of state of the most powerful of what were called the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria), he was the focus of popular animus throughout the war. He was the figure in the editorial cartoons appearing in the publications of his opponents, France, Britain, Italy, Russia and the United States. Perhaps only Hitler was reviled by his enemies more than Wilhelm. When revolt in his country and exhaustion by his army forced his abdication in November of 1918, he went into exile in neutral Holland. His first refuge was the unadorned, three-story brick castle at Amerongen belonging to Dutch Count Godard Bentinck. The victorious countries, trapped by their wartime propaganda which placed the blame for the war on Wilhelm, began to agitate for his arrest and trial. However, Holland1 refused to surrender the imperial refugee. This set the stage for a serio-comic incident.

Luke (apparently his real first name) Lea was 39 at the time. He was born in Nashville and graduated from The University of the South at Sewanee and Columbia Law School in New York. He returned to Nashville to practice law but soon became interested in journalism, becoming the founder, editor and publisher of the Nashville Tennesseean. A Democrat, he was the last U.S. senator from Tennessee to be elected by the legislature, as opposed to popular vote. He was defeated by Kenneth McKellar and left office in early 1917. The United States declared war on Germany shortly thereafter.2

Lea volunteered for the Tennessee National Guard and was made colonel of what became the 114th Field Artillery in the American Expeditionary Forces sent to Europe. They apparently arrived in England in the spring or summer of 1918. Lea left an account of the adventure, which is the subject of this essay, not written until 1935.3 In his account, which is the chief source for not only this article, but all the other published accounts, Lea reveals considerable Xenophobia. This is first manifested in his contempt for the mustachioed British Duke of Connaught, brother of King Edward VII and uncle of the then King, George V, because he wore medals. Lea was ignorant of the Duke’s extensive military service entitling him to the medals.4 Lea’s unit was paraded before the Duke for review, and the officers were invited to take tea with him afterward. Making conversation, his comment that he was not only King George’s uncle, but that of the Kaiser, struck a note in Lea’s head. The germ of his plan to capture the Kaiser was born, although the war was not to end for several months. For some reason, Lea assumed that the British Government wanted to protect the Kaiser, perhaps because of the royal relationship.5 He also formed the opinion that the “Allies,” (presumably meaning France, Britain, and Italy, since the U.S. was technically not an ally), had informally sanctioned Holland’s offer of asylum for the Kaiser. But he also believed that the soldiers and peoples of the Allied nations hated the Kaiser so much that his delivery into the hands of any allied “chieftain” would result in his trial and punishment. Furthermore, he thought even the German people would understand that they had been mistaken in their obedience to the ruler.6

The Armistice went into effect on November 11, 1918. Shortly before that the Kaiser had fled to Holland, but the war was not over, only the fighting. Although Germany was clearly beaten, there was a peace treaty to be arranged, and President Woodrow Wilson was coming to France to negotiate it with the British, French, and Italian leaders before forcing it on Germany’s new government. Colonel Lea was inspired by the idea of kidnapping the Kaiser from his place of refuge and presenting him to Wilson for trial and punishment. Lea was due some leave, so he obtained it from his brigade commander for the period from January 1 through January 5, 1919, “with permission to visit any place not prohibited by orders from General Headquarters…” Apparently Lea himself worded the order to suit his plans, and, when his general asked where he intended to go, he claims that he said that he didn’t want the general to have responsibility for the trip! Although puzzled, the general obliged.7

Lea selected seven8 of his men, all Tennesseeans, to accompany him on the adventure without knowing what they were going to do. Three of the men were officers: Captain Thomas P. Henderson of Franklin, Captain Leland S. MacPhail of Nashville, and First Lieutenant Ellsworth Brown of Chattanooga. The enlisted men were Sergeant Dan Reilly of Franklin, Sergeant Egbert Haile of Nashville, Sergeant Owen Johnston of Franklin, and Corporal Marmaduke Clokey of Knoxville.9 Henderson was a lifelong friend of Lea’s and McPhail was supposed to be “an accomplished linguist.” Reilly was an expert auto mechanic and Johnston “an unusual jack of all trades.”10 Although warning them that the trip might be dangerous, Lea did not initially tell the men of his intentions, and none asked any questions.11

Some accounts allege that Lea and his men were under the influence of “too many glasses of rum punch” and the enthusiasm of New Year’s Eve in putting their enterprise into action.12 Lea’s account modestly makes no reference to such intemperance, but other members of his merry band later wrote of the purchase of a quart of rum and two silver pitchers of hot water during a December planning outing, and a quart of Scotch whisky in January after stopping at Maastricht in Holland during the actual attempt.13

A first expedition to capture the Kaiser took place from December 24 to 28, 1918, but was aborted at the Dutch border for the lack of documents allowing entry into Holland. Leaving their post in occupied Luxembourg, they had motored through snow-covered Belgium and western Germany, only to be stopped at the machine-gun and barbed wire-festooned Dutch border. During this sprint, Captain Henderson noted that the Germans “look more like real folks than the French or Belgians [and] the towns look more like our towns and the people more like our own people…”14

The final expedition set forth at noon on New Year’s Eve day, all seven men in a clunky, brakeless Winton automobile belonging to the regiment, with extra gasoline and blanket rolls. They headed for Liège, Belgium, where they hoped to obtain papers permitting entry into Holland, but the car broke down the first night. Corporal Clokey was sent back to Luxembourg to borrow the regimental Cadillac of the sister Tennessee unit, the 115th Field Artillery.15

Meanwhile, Reilly and Johnston patched up the Winton and the party drove all night to reach Liège. There was a brief dispute with a Belgian officer over how much gasoline he could permit them was ultimately settled by Captain McPhaill’s fluent French (Lea said that he only spoke “broken Belgian,” perhaps meaning Flemish). Lea claimed to be astonished when the officer refused payment, “This refusal by a European to take money was the first…that ever happened to me on four trips abroad…”. MacPhaill had pointedly reminded the officer of America’s recent aid to Belgium.16

The Dutch consul in Liège could not supply entry papers for at least six weeks, so Lea got the bright idea of going straight to American Ambassador Brand Whitlock in Brussels. After all, while still a senator Lea had assisted Whitlock in obtaining his appointment. It proved an inspired idea, for Whitlock not only welcomed and fed the officers, but the dinner was also fortuitously attended by none other than the Dutch ambassador! Lea was introduced as not only a colonel but a senator. Lea alleges that he expressly denied being a senator any longer, but the impressed ambassador asked the purpose of his expedition. Lea replied, “journalistic investigations,” and this was the purpose written on the application for the Dutch laisser passer. Lea’s earlier journalistic pursuits in Tennessee lent some credibility to the claim, although the officials must have wondered why it took seven uniformed soldiers to “investigate.”

Photographs of the men were taken for their passports, each donning Lea’s overcoat because theirs were too shabby. When the U.S. passports were issued by the legation clerk, it was noticed that Lea was identified as a senator. Captain Henderson advised against accepting papers with this false information, but the clerk said he was out of passport forms and assured them that the notation was harmless. That afternoon, the Dutch Legation visaed their passports and Lea asked for a document specifically giving them authority to travel in Holland, in automobiles, in uniform. The document received read (in Dutch) as follows:

The little party found the Dutch document an “open sesame” at the border, and they entered Holland at 7 a.m. on January 5, 1919. At Nijmegen they stopped for lunch and one of the party later claimed that they there saw a regiment of English cavalry encamped, all within 30 miles of the Kaiser’s refuge. They allegedly believed that the British were “quietly protecting the Kaiser.”17 This seems highly unlikely, for the Dutch had jealously guarded their neutrality throughout the war and would not have allowed foreign troops on their soil, especially as the state of war still technically continued. Lea does not even mention this in his account. In any event, all agree that, while in Nijmegen, their presence attracted a small crowd, from which a boy about fifteen or sixteen emerged. “Interpreter, interpreter,” he volunteered. His name was Botter and he spoke somewhat broken English. The soldiers dubbed him “Hans” and hired him. They told him they would be in Holland several days and might not return to Nijmegen. He had no objection to that and only wanted to accompany the Americans and wind up in Maastricht.18

At dusk they found the Rhine bridge washed away and crossed by a ferry. However, they could not convince the ferryman to wait for their return, at which time they expected to have the Kaiser trussed up in their car. They understood, according to Lea, that without the ferry they could only bring him back with his consent. Lea claims to have believed that he might have been able to persuade Wilhelm to bravely “[face] in person his accusers” rather than remain “a craven coward,” afraid of his own people and the “Allied hosts of civilization.”19 In view of this assertion, one is tempted to conclude that Lea was either a fool or knew that what he proposed to do was just a stunt, which would give the folks at home a chuckle. Lea alleges (perhaps to protect his friends) that it was not until they were sixteen kilometers from Amerongen that he revealed his intentions to his comrades, none of whom demurred.20 Captain Henderson had hinted his own knowledge in a letter to his wife ten days earlier.21

The party arrived at Amerongen shortly before eight p.m., having received directions from a townsman. Lea claimed that his plan was to take advantage of the Teutonic respect for authority by simply ordering any sentry to allow entry. Sure enough, he claims, there was a man in Dutch military uniform at the gate, but Lea intuitively knew that he was really a “typical German ‘squarehead.’” Turning his flashlight on his Sam Browne belt and insignia of rank, he used his “guttural” German to order admission, and the sentry complied. Their knock at the front door was answered by a porter, whom they advised that they had important business with the Kaiser. They were ushered into the book-lined library where they saw large carved walnut chairs and the latest newspapers and Wilhelm’s stationery on a table. Their eyes also fell on several bronze ash trays, allegedly bearing the Kaiser’s monogram and crest. Soon the owner’s son, mustachioed Count Charles Bentinck, arrived, dressed in a tailcoat. Lea, who had majored in German at Sewanee, spoke to him in that language. Bentinck replied in English and politely asked their business, as everyone had retired for the night. Lea stalled a bit and then bluffed, “I can reveal the object of our visit only to the Kaiser.” Bentinck then retired to an adjoining room and could be heard speaking to someone.22 Meanwhile, Lea claims that their young Dutch interpreter fainted dead away and had to be dragged outside to the car by Lieutenant Brown.23

. . . some 150 to 200 Dutch troops with mounted machine-guns had arrived and surrounded Lieutenant Brown and the snoozing American enlisted men waiting outside. Searchlights played on the castle. . .

Lea’s officers could hear Bentick speaking to someone in the next room in “guttural” German or Dutch, sometimes saying, “your Majesty,” in one of the languages, presumably. He also was talking on the telephone. During this time, a butler “with a distinctive military bearing” (as Lea described virtually everybody at Amerongen) brought in ice water and cigars! Lea speculated that the unwilling hosts assumed that Americans were “teetotalers” and drank only ice water. Captain Henderson manifested indignation at this fare, and the butler returned with champagne.24 Other accounts state that they were served wine and sandwiches.25 Bentick had called the local mayor. He apparently spoke to the Kaiser also, for he returned to the library and told Lea that Wilhelm would not see them unless he was told the nature of their visit, and this Lea was not prepared to divulge to anyone but Wilhelm.26 When the mayor arrived, Lea attempted to speak to him in German for some reason, presuming one supposes, that Dutch was similar enough to be understood. The mayor politely pointed out that he was a graduate of Harvard and said, “I am sure we will progress more rapidly speaking in English.”27 At some point, Bentinck’s father Count Godard, the owner of the castle, joined the discussion. After further verbal sparring, the Europeans retired to the next room again for further consultation. Upon their return, they reiterated the Kaiser’s refusal to see them without knowing their intent. At this point, Lea brandished his ace in the hole, the letter of transit from the Dutch Consul in Brussels. Having studied the document, the Bentincks wisely inquired as to the meaning of “journalistic investigations.” “Was it a military technical term or did it mean newspaper investigation?” “The presence of you gentlemen here then is due to official business from the American government?” Were they from American Army Intelligence, or newspapers? Lea declined to elaborate or explain, thus leading to more next-room conferences by the frustrated Europeans. It can be surmised that they wanted to be sure that they were not dealing with some undercover diplomacy by the Americans, whose government, after all, was not technically an ally of Germany’s other enemies. Wilson had urged a peace based on his “14 Points”, rather than whatever spoils the other belligerents might seek.28

Finally, the mayor stated to the Americans that the Kaiser would see them if they gave their word of honor that they were there as representatives of President Wilson, AEF commander General John J. Pershing, or even Colonel House. This Lea was unwilling to do. Meanwhile, some 150 to 200 Dutch troops with mounted machine-guns had arrived and surrounded Lieutenant Brown and the snoozing American enlisted men waiting outside. Searchlights played on the castle. The lieutenant decided that Sergeant Johnston’s suggestion that they retrieve their pistols from beneath the car seat was not a good idea. Inside, Lea and his comrades realized that it was time to go, shook hands all round, and exited the castle at around eleven o’clock. Captain Henderson allegedly made the crack that such visits were an American custom.29

The Tenneseeans slowly drove through the Dutch soldiers and then made tracks for home. A short time later McPhail told Lea that he had a “souvenir” for him and the others. Before he could remove it from his pocket, Lea told him he did not want to know about it. In fact, it was one of the little ash trays they had observed in the library, and it was a souvenir. It depicted a small German shepherd dog smoking a long-stemmed pipe and was simply a cheap little German-made item for tourists.30 They dropped their young interpreter off at Maastricht as promised, and then one of the cars was involved in two collisions, running into a Dutch house and knocking a young man off his bicycle. They offered a 20 franc note to the unhurt Dutchman, but he refused it three times, earning the description from Lea of “a new, hitherto unknown species of European man…”31 They were subjected to European avarice again when they reached Luxembourg and requested gasoline from a French Army unit there. The commanding major would only sell one liter, as “he didn’t care to have Americans in his town,” Lea claims to have understood him to say. The “typical” French corporal assigned to the task was “so lazy” that he had not removed his cigarette from his “dirty lips.”32

Meanwhile, the Kaiser’s entourage had discovered the theft of the tiny ash tray and telephoned to Arnhem and Nijmegen in an attempt to head the thieves off—but too late. Wilhelm was amused. “Outside ten policemen, inside a robbery!” he commented.33 The culprits had already crossed the border, and thirty-six hours later were back at their regiment. Lea was just in time to mount his horse and lead the review of his unit.34 They were twelve hours past their leave time.35 In an apparent attempt to distract attention from his still mysterious mission, Lea told his commanding officer that he had discovered some vital information which he wanted to report in Paris to President Wilson’s aide, “Colonel” E.M. House. His general would not fall for that, but allowed him to write his findings to House. Lea then concocted a letter to House in which he asserted, among other things, that Britain and Belgium were colluding against other nations, Belgium planned to acquire part of Holland, German and Dutch merchants desired an entente between Holland, Germany, Russia and Japan in opposition to England, France, Italy and the United States. Also, that practically all Germans still loved the Kaiser and Field Marshal von Hindenberg. He threw in that he had some “facts relative to the Dutch Army and radio communications,” and also purported to know “the military status of the former Kaiser.”36 If, indeed, this preposterous missive was ever sent, or received, it met with the fate which it deserved. No answer or even acknowledgment was ever sent.37 Lea decided to at least attend the Peace Conference at Versailles as a spectator and obtained leave to do so. Using bluff and connections, he managed to be admitted.38 By this time, the press had published accounts of the escapade and the Kaiser’s suite (or the Dutch) lodged a formal complaint with the Americans, complaining not only of the stolen gewgaw, but that the visit made the Kaiser nervous. It probably made a lot of people nervous, for the new republican German government was simultaneously dealing with rumors that the German Crown Prince, who had also taken refuge in Holland, might be kidnapped by right-wing Germans. If so, the Kaiser’s son would then be used as a figurehead for counter-revolutionary forces.39

The U.S. Army began an investigation of the affair on January 26 and it continued for several weeks. They soon obtained the only real information which Lea and the others had obtained from the trip: that the Kaiser was neither ill nor insane and that he had a loyal retinue with him at Amerongen. Several charges were considered against Lea. First, that he had violated the General Order which forbade entry into neutral countries without permission from Army General Headquarters. Lea replied that the order was intended only for enlisted men, and his had acted under his orders. He pointed out the apparently inconsistent General Order which said that officers could go anywhere on leave except Paris. The second charge was using government automobiles on leave. Lea countered that this was a universal custom by officers, and noted that General Pershing also followed it. Lea threatened to call Pershing as a witness. This seemed to squelch any desire to prosecute Lea on the two charges. However, the next day a brigadier general advised that the Kaiser was preferring charges that the visit made him nervous and that an ash tray had been purloined.40 As to the first charge, Lea was told that he had the right to face his accuser: Wilhelm. Lea added that he had the ambition that every American soldier in the war had, to make the Kaiser as nervous as possible, and so he would plead guilty to that and later make $1,000 a week in Vaudeville as the only soldier who had been proved to succeed.41 When questioned about the ash tray, Lea replied that all he knew was “hearsay,” and thus inadmissible in a trial. That seemed to satisfy the investigator for a while. Shortly thereafter, Lea lunched with Captain McPhail, who admitted the theft. Lea asked to be his legal counsel and he accepted. Therefore, when the investigation resumed, Lea was able to say that his knowledge was privileged, as gained from his client.

The prosecution now fizzled out. But this was the U.S. Army, and some response to the international incident had to be made. The result was a formal letter to Lea from the Adjutant General of the American Expeditionary Force, sent at General Pershing’s command, finding that Lea’s actions, although “free from deception” were “amazingly indiscreet,” and he should never have entered Holland without orders. The more serious offense, however, it said, was making the visit without authority of the President, as its purpose might have been misunderstood “in some quarters,” “as indeed it was” and might have caused disastrous political and military consequences.42

Some months later a general told Lea that Pershing’s private comment was, “I’d have given a year’s pay to have been able to have taken Lea’s trip into Holland and to have entered the castle of Count Bentinck without invitation.”43

Back in civilian life, Lea purchased several Southern newspapers, including the Memphis Commercial Appeal for a time. He was a frequent political enemy of “Boss” E.H. Crump of Memphis and entered into banking and business with Rogers Caldwell of Caldwell & Co.44 The latter and the 1929 crash precipitated his downfall and he was convicted of banking fraud in North Carolina and served time in prison. General Pershing is supposed to have written a letter asking clemency for him. Perhaps he remembered the attempt to kidnap the Kaiser.45

Robert A. Lanier was born in Memphis in 1938, and has spent most of his life in the city as an attorney, with stints serving as a Circuit Court judge from 1982 until his retirement in 2004. Lanier also served as an Adjunct Professor at the Memphis State University School of Law (U of M) in 1981. He was a member of the Tennessee Historical Commission from 1977 to 1982, and was a founder of Memphis Heritage Inc., the historical preservation group still active today. He is the author of several books about Memphis history, including In the Courts (1969), Memphis in the Twenties (1979), and The History of the Memphis & Shelby County Bar (1981), and his most recent, Memphis in the Jazz Age (2021). He is proudest of his book The Prisoner of Durazzo (2010), about the king who postponed World War I for a year. Lanier also donated hundreds of his personal historic Memphis photographs to the Memphis Room of the Memphis Public Library – part of Lanier’s personal interest with Memphis history and historic preservation – and they can be viewed on the library’s digital archive and collection (DIG Memphis) under the Robert Lanier Collection.