1969 – 1971: The Lumbering Saga of Grace Slick, Chairman of the Board

Visitors to Playhouse’s executive offices have occasionally commented on an ugly, yet beloved bit of memorabilia: a battered 2-by-4 splattered with paint, its ends chewed up with nail holes and the words “Grace Slick” painted on the side.

In an industry that consumes building materials like a small construction company, this board exemplifies the conscientious organization Playhouse strived to be. In those early days, many of their technical accomplishments were the result of donated materials, which they often recycled from show to show.

They’d pry nails out of lumber so the boards could be used in the next production. After moving to their second address at 1947 Poplar Avenue, they did the math and realized one board had braced scenery in every show going back to their very first, The Fantasticks, in 1969. The 2-by-4 started out at eight feet long but was now down to six. The shredded ends — a result of being nailed to the floor to brace flats — had been trimmed down as needed. It wasn’t hard to keep tabs on the board; a technician had christened it after his favorite psychedelic lead singer from Jefferson Airplane.

After three years of constant use, Grace Slick retired to a comfortable life as a conversation piece that still reminds them to reuse and recycle as much as possible

1969 – 1973: Friends in All the Best Places

Tennessee Williams may have coined the phrase, “I’ve always depended on the kindness of strangers.” But from the early days of Playhouse, they have depended — indeed, survived — on the generosity of friends.

Starting a theater company required countless hours of unpaid volunteer labor. Many of their actors and technicians worked part-time jobs did so to buy basic necessities, chiefly food.

Enter Mike and Janice Holliday and Mike Bothne. They ran a local salvage company called Best Sales, which generously donated building and production materials acquired from businesses that had closed. They earmarked bolts of fabric for costumes. Their donated metal sheeting can be seen on the bathroom walls and front desk of TheaterWorks, built in the 1990s.

But Best Sales kept other wolves at bay, too. Many queries were rewarded with boxes full of dented cans of meat, soup and beans — food for starving artists.

One year, after a hurricane on the Gulf Coast had destroyed a liquor store, Best Sales let them know they had a hundred tempest-tossed cases of wine available for their noble cause. The bottles were uncorked for opening nights over the course of several years, amounting to an enormous savings on refreshments. Support for the arts takes many forms — some dented, some fermented.

Summer 1971: Midtowners

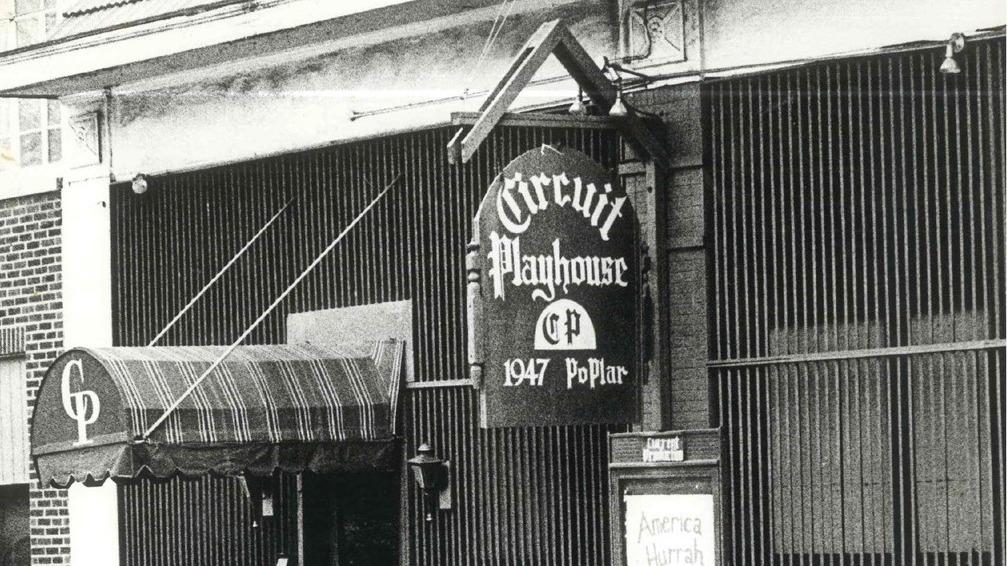

Losing their first theater space near the university seemed like a disaster. With a 60-day notice, they scrambled to find a new place to perform. That brought them to a row of storefronts at 1947 Poplar Avenue, just across from Overton Park. The theater loaded in next to merchants selling tropical fish, electronics, groceries, and liquor.

The rent went up, too, from $175 a month to $500. But there were advantages. For one, it was twice the size of the dance studio. There was also central heating and air — a marked improvement over the roaring window unit that cooled the previous building.

Best of all, the company had arrived in Midtown, the bohemian heart of Memphis. One of the company’s biggest supporters at the time was a wonderful lady with a legendary connection. Marion Keisker MacInnes is remembered in rock biographies as the front-office assistant at Sun Studio who, in 1953, was the first person to make a recording of Elvis Presley and recommend him to Sam Phillips. She was also a graduate of Rhodes (then Southwestern), a radio announcer, the local president of the National Organization for Women, a U.S. Air Force officer, and an occasional actress.

In one memorable performance, Keisker MacInnis starred in the two-person Pulitzer Prize winning drama ‘night, Mother alongside Jo Lynne Palmer.

“Marion played a lot of older character roles,” remembers Jackie Nichols, “and she did them brilliantly. She was a kickass woman.”

Keisker MacInnis also headed up a fundraising campaign to acquire seats for the new space. They were purchased used from a local movie theater called the State Theatre for $10 a chair. The theater seated about 100 people. The following year, they rented a one-story house just behind the theatre. The rooms were used for costumes, rehearsal, and actor housing. With little concern for fire codes, they transformed the shotgun style attic — a cozy 10’ X 30’ space — into a small secondary performance space, which seated no more than 25 people.

The Workshop Theatre was sweltering in the summer and freezing in the winter — as one might expect an attic to be. But it featured some intimate, memorable performances, including a production of the two-man Edward Albee play Zoo Story. It starred a Memphis State theater school drop-out named Michael Jeter, who spent several years as a company member.

Jeter went on to win a Tony Award for Grand Hotel (1990), an Emmy for his work on the television series Evening Shade and a Screen Actors Guild Award for ensemble work in the film The Green Mile.

Circuit Players spent nine years at 1947 Poplar Avenue before the landlord and former cotton magnate Julian Hohenberg turned the entire complex into an indoor ski slope.

Want more Playhouse on the Square history? You can read Parts 1 and 2.

Christopher Blank is WKNO’s News Director, a frequent contributor to NPR, and moderates conversations about Memphis’s arts and culture community through the station’s Culture Desk Facebook page. He wrote this history of Playhouse on the Square for the theatre’s 50th anniversary.