1975: New Look, New Logo

The Playhouse on the Square logo may have an Art Nouveau vibe, but it was in fact designed in 1975 by the renowned Memphis artist Frank Morris, whose portraits of civic leaders hang in the courthouse. He even designed the back of a 2017 quarter for the U.S. Mint.

Morris was recommended by one of Overton Square’s founders, Ben Woodson. People have wondered if it’s a man or a woman and the response has always been the same: it’s whatever you want it to be.

The logo depicts a figure peering out from under the mask of a lion, which references the Greek theater tradition. Morris first created a similar image for Opera Memphis, but the company didn’t care for it. For Playhouse, he offered a number of different hair (or mane) treatments, and this was the favorite.

The logo won a national design award after its completion. For years, they have gotten compliments about their logo from people all over the country. Thanks, Frank Morris!

Spring 1975: The Square Gets a Playhouse

Early in 1975, Ben Woodson, one of the principal owners of Overton Square, approached Jackie Nichols with a tempting business offer.

Lafayette’s Music Room on the square had been a popular venue for live concerts, but it was suffering financially, in part because the intimate space prevented bigger acts from turning a profit. (These were the days you could sit just a few feet away from Billy Joel, KISS, or Barry Manilow on a given night.) The owners also realized that the rock and roll crowds were not patronizing the restaurants next door and were sneaking liquor in, to boot. Some revenue may have been creeping out the back door.

Woodson proposed turning Lafayette’s into a theatre. That audience, he figured, would more likely dine out, pay for drinks and come back for more. Programming was their first major concern: they didn’t want to sacrifice cutting-edge drama for the expectations of profitability in an “entertainment district.” The solution was that they would open a separate arm of our not-for-profit Circuit Playhouse, which was still at 1947 Poplar. The distinction was that shows on the square would have popular appeal and use paid actors and technicians, i.e., a professional company.

In many ways, the first iteration of Playhouse on the Square was a leap of faith. The deal came together quickly with not much long-range planning. They had practically no money to renovate the space, so Woodson and Overton Square contributed significantly to the undertaking. For about $40,000 ($190,000 in today’s money), they purchased auditorium seats from an old movie theater, installed dressing rooms, fixed the plumbing, put in new carpeting, painted the walls, and added some lights.

The construction lasted several months. During that time, they also put together a season, a staff, a company, and started selling subscriptions. On the evening of November 12, 1975, Playhouse on the Square made its Memphis debut with Godspell directed by Larry Riley, who co-starred with Michael Jeter. For the first time since the closing of Front Street Theatre in 1968 Memphis had a professional theatre company.

After the excitement of opening died down, they finally got around to asking: “What have we gotten ourselves into?” Overnight their budget grew from $35,000 to $175,000 with no grants or sponsorships to cover the increase. Their new “professional” office space was a 10-by-10 room with a 6-foot-high ceiling and three desks. They held business meetings over Bloody Marys across the street at the Bombay Bicycle Club.

For a few years, Playhouse was an integral part of Overton Square’s first heyday, when actors could make extra money singing in restaurants or dressing as Dickensian revelers during the holidays. The Overton Square owners believed in them, the board believed in them, and the Memphis theatre-going public supported them.

Memphis, Tennessee, had a professional company again paying actors after the demise of Front Street Theatre in 1968. Theatre seating from a soon-to-be-closed movie theatre, dressing rooms, plumbing, electrical, some new lights, equipment, carpet, signage and paint into a legitimate theatre with theatre seating from a rock and roll venue with table seating.

1975: Earth Moving

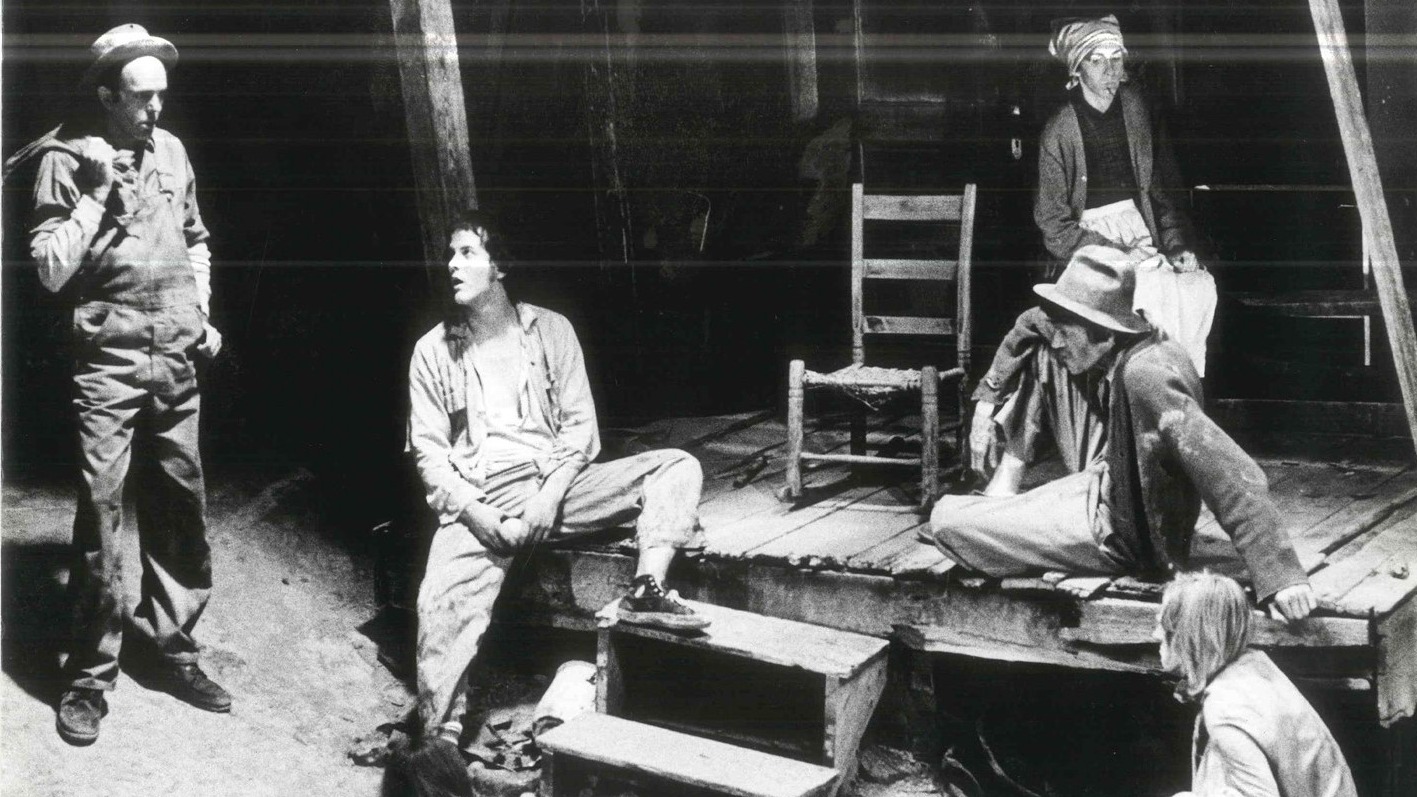

When scenic designer Greg Peeples learned they were producing the play Tobacco Road set in the rural Depression-era South, he decided that a naturalistic approach might be worth the effort. Effort being the key word.

The playing area had three-quarters seating, so they turned the entire stage into a farm. First came the landscape, a dump truck full of dirt. Instead of building a house with a porch and weathering it the usual way, they found an abandoned shack in the country, dismantled it, then reassembled it inside the theatre. They even had a working water pump.

Worms, insects, and other creepy crawlies came with the soil. So did the smell. Critics and audiences raved (in a good way). During the course of the run, the earth in one corner of the set rose inexplicably. Actors changed their blocking to move around this foot-tall bump in the ground, which started to resemble a fresh grave. Striking the set, they learned that a leak in the water pump had caused the hardwood flooring to buckle upward — an unexpected repair cost. But if budgets were measured in sweat and toil, getting rid of the dirt was out biggest expense.

Moral of the Story: Never Load in with Shovels What You’ll Be Removing with Brooms.

March 1976: Getting Site Specific

A year after bringing the environment to the theatre with Tobacco Road, they brought the theatre to the environment in what was, perhaps, the most ambitious “site specific” production in the company’s history.

Hot’l Baltimore is a comedic drama set in a soon-to-be demolished hotel in Baltimore, Maryland. As it happened, Memphis had its own soon-to-be demolished hotel Downtown.

Staging the play in the abandoned lobby of the Hotel King Cotton came with its own set of challenges, but thanks to youthful ignorance, they charged ahead in spite of them. Once the owners gave them permission to use their property for this harebrained idea, they secured a million-dollar insurance policy for any accidents that were far from improbable given the state of the building. Because the production was an addition to the regular Circuit season, they had to assemble a separate technical staff to carry out this undertaking. Fortunately, the prospect of turning a ghostly hotel lobby into a theatre prompted a chorus of “Oh my God, this could be awesome.”

Theatre Management 101 contains scant advice on what to do if your venue has no electricity or working plumbing. To solve the first problem, they had an electrical company run power up to a breaker box from the spot where MLGW service previously entered the building, a dank basement two stories underground. For restrooms, they ordered a row of Port-a-Johns to be brought inside the building. Once a week for a whole month they carted them back outside for emptying.

After the interior needs were taken care of, they moved to the outside. The show’s title Hot’l Baltimore references the derelict state of its neon sign, with a short-circuiting ‘e’ in the hotel marquee. Ron Pekar, a neon artist at the Memphis Art Academy, built two large, functional 12- by-10 marquees – one for each side of the existing (and also derelict) Hotel King Cotton sign. A theatre patron paid for the cost of both and got to keep one. On opening night, the audience entered through the front door of the building.

Seating was arranged throughout the lobby, where the action of the show takes place, essentially sharing the stage with the performers. Additional seats were added to the mezzanine above the lobby, so some patrons watched from above.

The production ran during one of the coldest Marches on record. Space heaters were brought in to create a resemblance of warmth in the cavernous space. Blankets distributed to audience members kept people from freezing to their seats. At the end of the first act, one character — the resident prostitute — is supposed to descend the stairs wearing only a towel, which gets discarded for a brief nude scene. The actress literally came down with a case of cold feet (and other extremities) and refused to be totally naked underneath.

Despite the challenges, the show was an enormous success. The entire run sold out. Shortly after Hot’l Baltimore took its final bow, the curtain closed for good on the Hotel King Cotton.

1977: Waterworks

The success of Hot’l Baltimore sent them looking for another site-specific show the following year. Their location scouting led them just across the street from the rubble of the former King Cotton Hotel. The Pilot House Motor Inn had a rooftop pool on the 9th floor and somehow, they convinced them to let them use it for three weeks in the middle of summer.

The perfect show for this project was The Frogs, a musical by Stephen Sondheim and Burt Shevelove, based on Aristophanes’s play. One of Memphis’s most prominent visual artists, Dolph Smith, designed the set with Jackie Nichols.

The concept, a pond full of lily pads, required draining the pool, painting the substructure with blue waterproof paint, then refilling the pool. An additional backdrop was made out of plastic prism pieces. As the sun set, it transformed into an enormous rainbow.

Actors jumped from lily pad to lily pad. Once again, the gods of the theater (who are Greek, remember) granted us an injury-free run. In a brazen act of pressing their luck, they invited audience members to bring bathing suits and go for a swim after the performances.

Want more Playhouse on the Square history? You can read Parts 1, 2, and 3.

Christopher Blank is WKNO’s News Director, a frequent contributor to NPR, and moderates conversations about Memphis’s arts and culture community through the station’s Culture Desk Facebook page. He wrote this history of Playhouse on the Square for the theatre’s 50th anniversary.