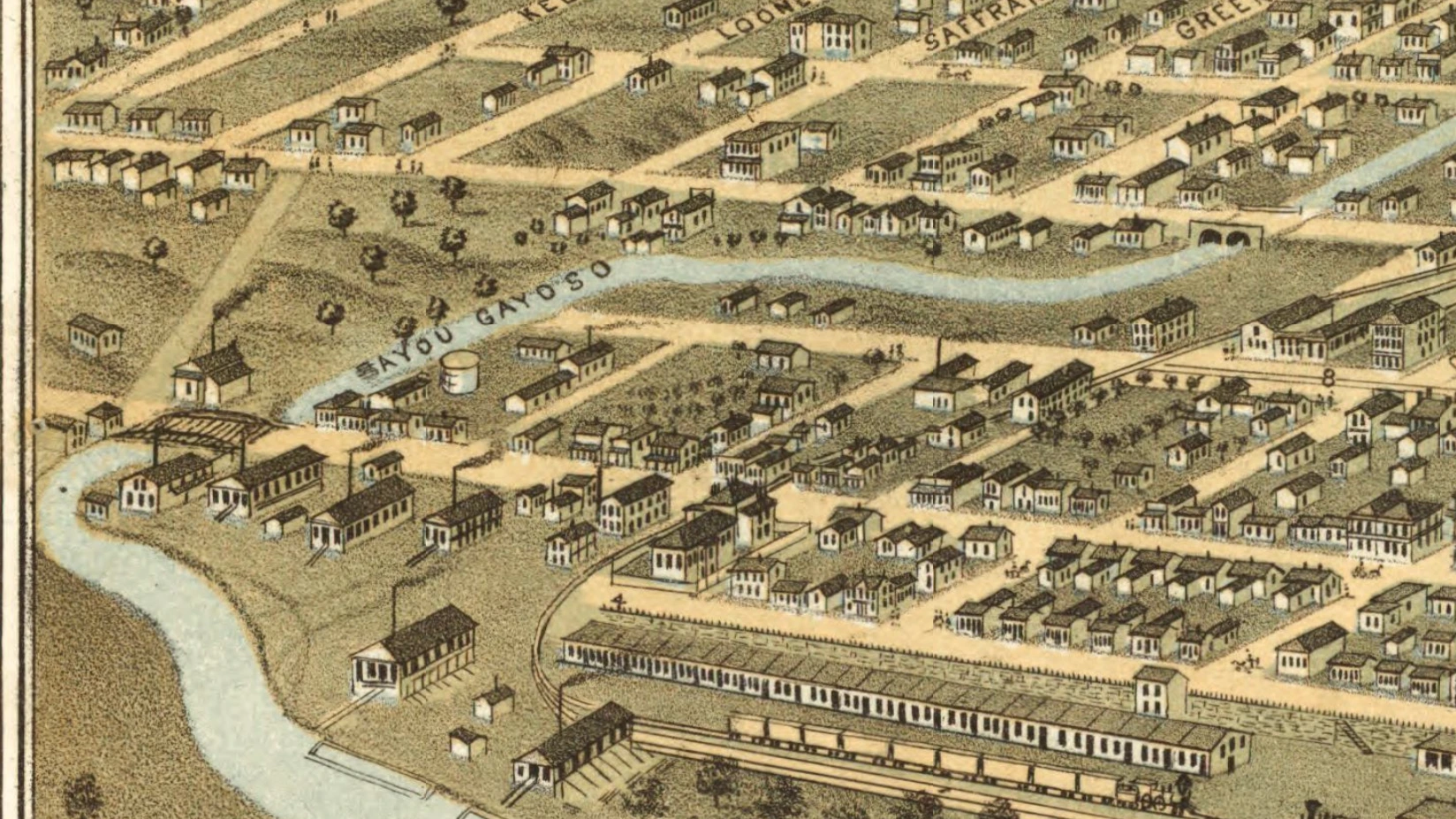

Beginning as an open floodway and transformed to an underground drainage system, Gayoso Bayou has become one of Memphis’s hidden waterways. “Bayou” can either refer to a slow-moving creek that drains into a larger stream, or a swampy section of a river or lake. The Gayoso fits the creek part of the definition. For most of its natural history, this waterway stretched for five and a half miles and was part of a larger bayou system that drained an estimated 5,000 acres. It had east and west forks and two tributaries, the Little Betty and the De Soto. It flowed in a northerly direction before receiving the Quimby Bayou and then emptying into the Wolf River, which in turn emptied into the Mississippi.

Within Gayoso Bayou was a section called Catfish Bay, a lake created by a bend in the waterway. John M. Keating, one of the city’s first historians, writing in 1888 located Catfish Bay, “immediately north of where the Memphis and Ohio railroad depot now is, where there is a considerable bend in the bayou, which once constituted a considerable lake. Its original beauty has been destroyed, and the bed to some extent filled up by the building of the heavy embankment on Second Street through it.” According to the 1939 Federal Writers Project, Catfish Bay was “a small lake north of Jackson Street.” A 2015 Memphis Business Journal article identified part of the lake’s location to have been the current corner of 4th Street and A.W. Willis Avenue.

For the first decades of Memphis’s existence, Gayoso Bayou formed a useful geographic boundary. It served as the city’s original eastern limit. In 1828, Marcus Winchester, a land developer and the city’s first mayor, sold one acre lots that stretched “as far back as the Bayou Gayoso.” As the city expanded, locations of city wards were defined as either west or east of the bayou. Imagine an open creek bed running through the city, with footbridges spanning the bayou where roads cut across the waterway.

Catfish Bay developed into a shanty town in the North Memphis Pinch neighborhood, an area with many poor, Irish residents. River workers anchored flatboats and houseboats along the bay since it was protected from the Mississippi’s current. Memphians in other parts of the city came to see Catfish Bay as a nuisance, and Mayor Issac Rawlings tried to raze it in 1830. He met with fierce resistance from the people living there. Vigilantes forced the issue by overturning boatloads of tannery ooze and animal waste into the bay and making it an unfit place to live. The bay’s historical marker, put up during the city’s Sesquicentennial celebration in 1969, has been missing for decades.

Given that the Gayoso is a floodplain, it is unsurprising that the built environment near the bayou was prone to flooding. Heavy rains in April 1878 “turned Bayou Gayoso into a roaring and mad torrent, which went seething and whirling into Wolf River and out into the Mississippi,” washing out foot bridges along the way, according to the Memphis Daily Appeal. The Public Ledger reported a year later that flooding meant the creek “was putting on the airs of a big river…an ocean steamer could now ascend Bayou Gayoso from its mouth to within ten inches of its source were the bridges removed.” Whenever the bayou flooded, it took homes, horses, and sometimes people with it.

Gayoso Bayou was also noxious. Memphis was an odorous city in the late 1800s, and the trash and sewage clogging the bayou between rainfalls didn’t help. In 1892, a visitor from Statesville, North Carolina described the Gayoso Bayou’s banks in the Statesville Record and Landmark as “decorated in basso relievo with broken crockery, tomato cans, old shoes, beer bottles, and at intervals a dead cat or a goat…From such festering, fever-breeding sewers, epidemics arise…”

During Memphis’s devastating yellow fever epidemics, people were quick to place blame on the Gayoso Bayou. In 1878, people believed the disease spread along the nasty, sewage filled waterway, but a 2011 geographic survey found that year’s epidemic spread north and south along road networks, particularly Main Street and Second Street, much more than along the bayou’s course. Nevertheless, sanitation engineers targeted Bayou Gayoso for improvements in the following years.

The City also built a pumping station at Main Street and Saffarans Avenue in 1912 to remove water from the bayou when it got too high. That station impounded the water at Catfish Bay, which Mayor E.H. “Boss” Crump and his new commission government advertised in 1912-1913 as a municipal pool complete with bath houses, slides, and diving boards.

Beginning at the turn of the twentieth century and continuing through the 1930s, the City slowly buried most of the bayou in a continued effort to provide a solution for the occasional flooding. Through channeling the stream into conveyance tunnels and paving them over, the former city boundary moved underfoot. New Deal legislation during the Great Depression provided funds and laborers to finish the process. But water can be difficult to contain, and FEMA classifies the area as a flood zone, one “protected by the levees but subject to failure upon large flood events” such as pumping station failure or a severe rainstorm.

The engineers have been changing the bayou - - - it goes underground here, it goes underground there, here it becomes wide and deep enough to hold a spring river's back wash, here it is narrow, a trickle running beneath the back houses which are no longer supposed to exist in our sanitary city, and finally it is tunnelled through the bluff where it meets the Wolf, Nashoba, with a different mouth than it once had. It trickles into the Wolf. It does not gush as once it did when nothing worse than geologic accident had altered it. Excerpted from Bayou Gayoso by Kenneth Lawrence Beaudoin, 1953

Today, the waterway mainly flows through underground tunnels and mostly follows Danny Thomas Boulevard and Lauderdale Street. A portion of the bayou is exposed at Loflin Yard and can also be seen running through empty lots near St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. St. Jude/ALSAC has proposed a parking garage atop this property. Residents of the Greenlaw and Uptown neighborhoods argue that the proposed building may increase flooding in the neighborhood.

The Gayoso Bayou may have been out of sight for generations, but it is certainly not out of everyone’s minds.

Caroline Mitchell Carrico is a native Memphian and, as a historian by training, she enjoys researching the city’s past and pulling it into the present. When she isn’t reading and writing, she can often be found cheering on her kids’ soccer teams.

What a fascinating read! Love the early history stories, and thanks for this one.

Fascinating story. Thank you for researching this Memphis reality.

Great story, Caroline!

Thanks, Dave! It was fun to research.

Not sure why the Gayoso Bayou crossed my mind this morning—thank you for this research and information!