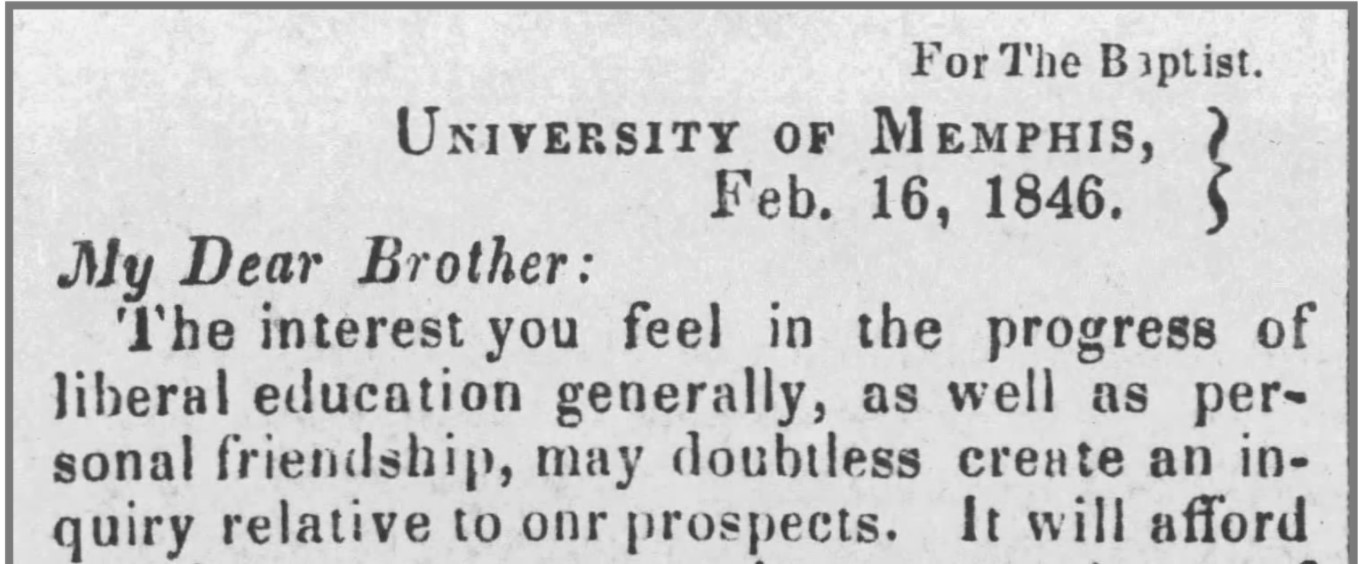

The University of Memphis, with its multiple campuses, R1 research designation, and high achieving NCAA Division 1 sports program, is an anchor in the Memphis community. Beginning in 1912 as the West Tennessee State Normal School, the university has had many names – West Tennessee State Teachers College; State Teachers College, Memphis; Memphis State University; and finally, in 1994, The University of Memphis. However, it’s not the first school with that title.

Almost 150 years before the current UofM took on the name, the State of Tennessee granted a charter to the first University of Memphis, which began enrolling students in 1846. Memphis’s geographic footprint was much smaller at that time, and one of the city’s rivals for residents and railroads was Fort Pickering, an unincorporated community laid out in 1840 and boasting the western terminus of the Memphis and LaGrange Railroad. The neighborhood stayed outside of the Memphis city limits until 1868. The new school’s trustees located the University of Memphis in this neighborhood in a large building that was originally built to be a hotel. The building had “spacious halls for chapel and other uses, rooms for class exercises, for the separate occupancy of students and commons, ample and convenient apartments for the presiding officer.”

The trustees were a veritable who’s who of Memphis at the time. The list included Dr. Jeptha Fowlkes – an editor of the Daily Avalanche, founder of the Tennessee Club, and a president and major stockholder of the Southern Pacific Railroad; banker and landowner Geraldus Buntyn who had donated the land for First Baptist Church at Second and Adams and served as a delegate to the Convention of 1845; Seth Wheatley, a lawyer and the mayor of Memphis from 1831-2; and Dr. Lewis Shanks, a founder of Calvary Episcopal Church.

These men, along with the other trustees, passed resolutions to obtain a library and solicit donations for scholarships, professorships, and equipment. They applied to the mayors of both Memphis and South Memphis (at that time, a separately incorporated city) to request that some of the revenue generated from the state’s 1846 Tippling Law, which levied a license fee on bars and saloons, be allocated to the university.

The unanimously elected faculty included Rev. Benjamin Franklin Farnsworth, president and professor of intellectual philosophy and moral science, Rev. Thomas Baldwin Ripley, professor of Latin and Greek languages, Rev. J.H. Gray, professor of mathematics and cultural philosophy, and T.R. Farnsworth, “tutor in mathematics & etc.” There were instructors for the arts, medicine, and law. The faculty lived in the college buildings to “exercise a constant control over its interests.”

By the time of his appointment, Farnsworth had already had a distinguished career as a Baptist educator. In the mid-1820s, the editor of the Christian Watchman was named principal at the New Hampton Institute, a position he held until 1832. From 1836-7, he served as President of Georgetown College, a Baptist institution still located in Georgetown, Kentucky, which presented him with an honorary Doctor of Divinity in 1847. In 1838, he was the first President and Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy and Political Economy at Louisville Collegiate Institute. (Louisville Collegiate Institute is now known as the University of Louisville. Quite the coincidence for the president of the first UofM to have also been the first president of UofL. This occurred decades before James Naismith invented basketball, a development that later linked UofL to the current UofM.)

The trustees ran ads in Tennessee and Mississippi newspapers, urging “parents who have sons to educate, can place them under the charge of the present Faculty, with the full assurance that every means will be employed to promote their moral and intellectual tenure.” For $25 per session, the college would educate their boys, and for an additional $10 per month, provide them board. (Those amounts are equivalent to $920 for schooling and $368/month for boarding in 2022).

They planned for the school to have three departments. The first was concerned with preparatory courses in reading, writing, grammar, practical math, algebra, geography, United States history, and an introduction to science, including natural history, botany, and geology. Classical courses in Greek and Latin could be added. More advanced students could enter the second department, which were considered collegiate courses. Students advanced through these four years of instruction in specialized departments of Latin & Greek languages, modern languages, mathematics and natural philosophy, rhetoric, belle lettres & history, and intellectual and moral philosophy. The third department, still being planned in 1846, was for professional education in medicine, law, and theology.

The school seems to have operated for a few years before fizzling out. On August 3, 1849, The Memphis Daily Eagle reported that the “Fort Pickering University Building, was, to all effects and purposes, consumed by the fire of last Monday. The blackened walls are alone standing, and even these are cracked in several places.” There is no indication that the university continued after the conflagration. It would be over a century until the city had another namesake university.

Caroline Mitchell Carrico is a native Memphian and, as a historian by training, she enjoys researching the city’s past and pulling it into the present. When she isn’t reading and writing, she can often be found cheering on her kids’ soccer teams.