This is the third in a series of articles in StoryBoard and Memphis Heritage’s newsletter, The Keystone, that are centered on the first Comprehensive City Plan for Memphis, dated 1924.

Up to now the series has described the need for a city plan and some of the many pertinent aspects that such a plan engendered, namely street plans (fostered by the arrival of the automobile in the 1920’s), and zoning issues necessitated by the need for orderly future growth of the city. The following information is primarily from the 1922 Report on the Comprehensive City Plan for Memphis that became part of the final Comprehensive City Plan by Harland Bartholomew, completed two years later.

The First Comprehensive Plan

Before we go into the critical area of zoning, there are a few more comments that are pertinent to the street plan matter facing the designers of the city plan in 1924. To a great extent, they had to work with what was already in place in many quarters; only in the outer districts, where development was not as dense, could they create the ideal street plan.

The Parkview Hotel being built in a residential neighborhood in 1920’s.

Mostly, though, the streets were already there, surrounded by all sorts of construction and infrastructure. An elaborate scheme that made proposals for radical revision of multiple streets and avenues was hatched, wherein some were widened; dead ends were opened; and unnecessary or problem streets were closed, renamed, or blocked to enhance traffic flow. Other interconnected thoroughfares were widened and/or merged.

In the following section on “Zoning,” an array of service maps addressing all angles of the proposed plan are shown to have aided zoning immeasurably. These and similar maps helped rearrange and alter the streets by width, direction, and pavement types; and anticipated current/future needs allowed the engineers to best reconfigure much of the existing roadway system and to plan new roads where needed. This plan had to take into account streetcar lines, areas of higher/lower population growth, railroad tracks, and a plethora of other considerations to make the city “work” to its best advantage.

Bartholomew did not get everything he wanted. There were cases where “sacred cows” or long-term commitments by the city existed — for instance, to the railroads that had saved the city from extinction in the previous century. He managed to work around that issue and to reach compromise on others.

ZONING

Zoning is the result of looking at the development of a city to date from its founding and recognizing the need to be more strategic in future development to benefit not only the needs of the citizenry and enhancement of land values, but also an intangible variety of activities carried on by any civilization in the modern world.

Living in a neighborhood, running a business of some sort, and providing utilities and services such as transit, are all integral parts of a comprehensive city plan. With zoning, the height and character of buildings, number of inhabitants of a particular district, other, more subtle, restrictions caused by already developed districts, and ordinances covering certain districts with unique characteristics, all occupied the full attention of the plan developers.

Ownership Rights vs. Zoning

Examples of the fuzzy questions facing planners included garages next to schools, factories and service stations in residential neighborhoods, and the intermingling of residences and apartments.

A commercial building in a residential neighborhood at the time zoning was begun in 1922. The caption reads: “A characteristic invasion which zoning is designed to prevent.”

The freedom of individual land owners about land use is a basic right unless it conflicts with the overall plan espoused by the city planners. Zoning is an amplification of the normal rules that can override ordinary rights of land owners if it is in the best interest of the community or essential to the orderly growth a city. Indeed, it is the legal exercise of the state police power under which all regulatory measures of a community are authorized. But should zoning desires override the sacred right of land ownership?

The Supreme Court

A 1915 syllabus Supreme Court case (Hadacheck v Sebastian, 239 U.S. 394) that centered on zoning rights in that early era of city zoning held that “there must be progress, and if, in its march, private interests are in the way, they must yield to the good of the community.”

That hard and fast rule may not be as readily enforceable today, but it was pretty definitive law at that time – just a few years before the zoning issue had to be decided for Memphis. After all, Memphis was the first city in Tennessee to adopt a comprehensive zoning ordinance, and it was supposed to reflect all the best elements of good zoning known at that time. The state’s police powers were new on the horizon when it came to use of owned land.

Again from the Hadacheck case, “While it is universally recognized that police powers must not be exercised arbitrarily as to deprive persons of their property without due process or deny them equal protection of the law, it is also clear that that power is one of the most essential and least limitable means for government to keep order. In fact, the imperative necessity for its existence precludes any limitations on it when not arbitrarily exercised.”

That’s a powerful provision.

The Zoning Process

The first step in the zoning process involved preparing an exhaustive and all-inclusive list of existing buildings within the city itself.

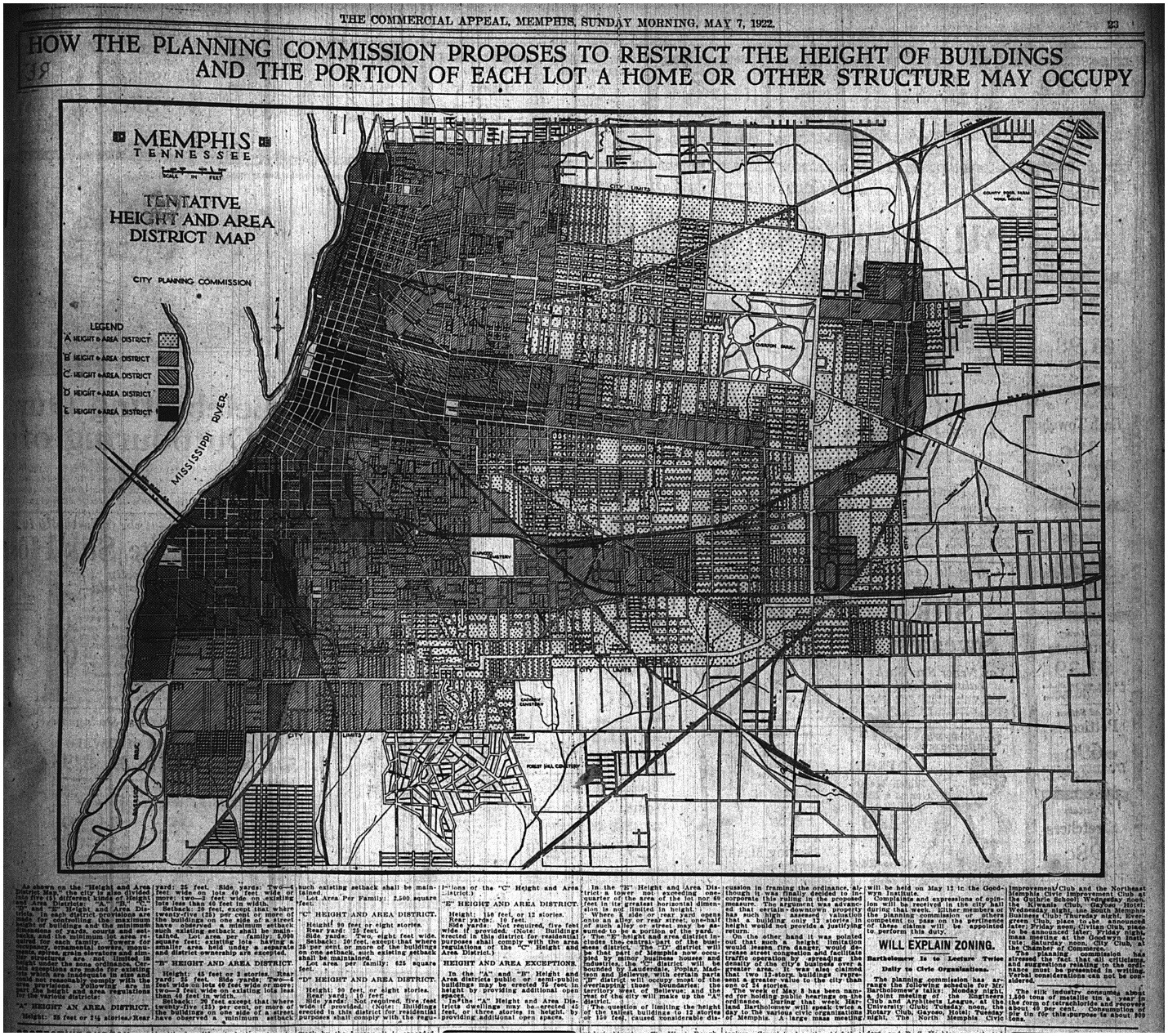

Intimate knowledge of what already existed was vital to future actions. The process included field surveys, various types of maps (i.e., study, use maps, and height, area, density, assessed land value, railroad/industrial, wind, and non-conforming use maps) to provide a visual means of analyzing characteristics of present and future growth tendencies and the percentage of current usage of lands and how they differed from the proposals in the zoning plan. Many of these and similar maps were also used in the street planning matter that preceded in-depth zoning plans.

In that regard, mapping revealed that the industrial use of land in the city was a mere 3.6% while the zoning plan set forth 15% as a desirable level. Commercial land use was at 1.2% versus a desired 6.3%. Residential use was already at 32%, but even there the plan prescribed a somewhat higher level of 40%. Streets, parks, and cemeteries were already on target at 38%. The study also showed that the available residential areas in the city would be exhausted if current growth patterns were left untouched.

Imagine the time-consuming, exacting procedures that went into this ordinance aimed at providing guidance for both present situations and future planning.

This was at a time when the idea of zoning was brand new to the country. Each district of the city faced its own restrictions on use, height, size of yards, courts, setback acreage, and even the square footage of each lot per family.

These planned rules were distributed and publicized at public hearings before approval by the City Planning Commission and transmitted to the Board of City Commissioners. They were adopted November 7, 1922, effective immediately.

Next time, we will continue to explore the role of zoning in the 1924 modern city plan that was but 2 years from adoption by Memphis. You will learn that it was not a hide-bound, inflexible dictate but one designed to accommodate the city and all its inhabitants while taking into account mistakes of the past and prospects for the future.

From the editor: StoryBoard Memphis is proud to be reviving the Memphis Heritage Keystone newsletter after a two-year absence. While StoryBoard will be the newsletter’s printed home, the Keystone will continue to be published and distributed to Memphis Heritage members via email and will be available online at www.MemphisHeritage.org.