This article originally appeared in Volume I, Issue III of StoryBoard Memphis Quarterly in July 2022.

In late 1796, Chickasaw Chief Ugulayacabé (you-guh-lah yock-uh-bee) appeared at Fort San Fernando de las Barrancas on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff to condemn Spain’s betrayal of their alliance. A year earlier, the Spanish had constructed the fort, located between the Wolf and Mississippi Rivers and the Gayoso Bayou on traditional Chickasaw hunting territory. Now the Spanish were abandoning the fort after a treaty with the Americans.

This incident proked Ugulayacabé to declare, “Under the pretext of justice, you will oppress us; perhaps whip us as you do your black men…Tell me if I can return to my village to quiet them and to assure our warriors, our children, and our women that what is written of the Americans is false, whether your [Spain’s] flag will always fly over our land or the Chickasaw should prepare themselves to die.”

What led to this moment above the Mississippi River?

Geopolitics in the Mississippi Valley, 1763-1783

Thirty years earlier, after the French and Indian War ended in 1763, Spain developed footholds along the Mississippi River, stretching southward from Illinois. Word reached the Chickasaw that the Americans planned to move west and settle in their Northern Mississippi homelands. American and Spanish factions formed within the Chickasaw Nation. Chickasaw war chief Piomingo saw the Americans as solid allies. Conversely, the Chickasaw coalition who had supported the French believed Spain was the most formidable ally in the Mississippi Valley.

The American Revolution sent shock waves throughout the First Nations of the Southeast. The Chickasaw viewed the revolution as a fight between brothers and did not want to take an active role. Spain declared war upon England to control West Florida. The Spanish forces took West Florida from the British with an overwhelming fleet of Spanish, French, and American troops, bolstered by Choctaw and some Chickasaw warriors.

Spain then claimed all lands from the Yazoo River to the Ohio River, which included the heartland of Chickasaw territory. The Chickasaw, having signed a peace treaty with Virginia and accepted Spanish trade and gifts, attempted to balance the favor of both nations. But within the Chickasaw Nation, old factions once again split their allegiance – this time between the Americans and the Spanish. Both America and Spain were anxious to build an outpost on the Chickasaw Bluffs in order to control travel and trade on the Mississippi River.

Chickasaw Diplomacy after the American Revolution

The surrender of the British at Yorktown in late 1781 meant that the Chickasaw needed to establish new relationships with the Americans. American settlers were pouring into Chickasaw, Creek, and Choctaw territory, and Spain was jockeying to control traffic on the Mississippi River.

After many of the older Chickasaw Chiefs died during a measles outbreak, war chief Piomingo and a lesser-known chief, Ugulayacabé, rose to leadership roles. Piomingo believed the Americans were the best allies to ensure the independence of the Chickasaw. Ugulayacabé believed that an alliance with Spain would stop the Americans from flowing into Chickasaw land.

The American and Spanish governments each publicly stated that Piomingo and Ugulayacabé were loyal allies and leaders of their Nations. The Chickasaw Villages each had chiefs of various aspects of Chickasaw life. The rank of one chief over another was a matter of a combination of bravado, skilled diplomacy, and distribution of goods. Neither Piomingo nor Ugulayacabé was recognized as chief of all the Chickasaw, a title that did not exist. Their number of followers depended upon their internal negotiating skills and the distributions of gifts that they received from either Spain or America.

The first formal meeting between United States representatives and the Chickasaw occurred in late 1783 at French Lick (now Nashville, Tennessee). Piomingo and James Robertson, a Virginian, arranged the meeting. The Chickasaw attendees included Piomingo and Mingo Houma, whom the Americans thought of as King of the Chickasaw. These two planned to stop American settlement on Chickasaw lands. Robertson and fellow Virginian Joseph Martin hoped to establish a trading post at French Lick and obtain lands near Muscle Shoals (Alabama). The Americans also hoped to acquire land on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff (now Memphis) to counter Spain’s control of the Mississippi River. The Spanish-leaning faction of the Chickasaw was opposed to allowing the Americans near the Chickasaw Bluffs. In the end, Chickasaw leaders refused to discuss any land cessions.

The Chickasaw chiefs, including Piomingo, drafted a letter to the new American Congress in which they extended their friendship as brothers. The document expressed their concern about all the competing offers of trade they had been receiving, including those from individual states, Spain, and the Illinois Confederacy of Nations. The chiefs asked to whom they should communicate to “rescue us from the darkness and confusion we are in.” This deferential-sounding phrase was part of their long-standing diplomatic language, not a statement of weakness. They told the Americans that they would maintain a trade relationship with Spain until the new relationship with America was resolved.

Treaties

In June 1784, Spain managed to bring both Chickasaw factions to a treaty meeting in Mobile, and Ugulayacabé and Piomingo attended. The Spanish offered guarantees of Chickasaw autonomy in exchange for releasing Spanish prisoners and the promise that Chickasaw warriors would drive out all non-Spanish traders. Ugulayacabé signed the Mobile Treaty of 1784. Piomingo, distrustful of future Spanish demands, did not. The American and Spanish factions wanted the same thing for their people, independence. For Piomingo, the goal of Chickasaw diplomacy was to keep “a people to ourselves.”

In response to the Spanish treaties of Mobile, the Americans arranged a meeting with the Choctaw, Cherokee, and Chickasaw at Hopewell, the North Carolina plantation of Revolutionary War hero Andrew Pickens. In the late winter of 1785–86, the parties negotiated and signed three separate treaties with each of the three nations. Piomingo, who had refused to sign the Spanish treaty of Mobile, signed the agreement with the Americans, believing the greater hope for independence lay with them.

The Americans and Spanish continued negotiations with the Chickasaw for land on the strategic Fourth Chickasaw Bluff. In Spring 1792, William Blount, governor of territory below the Ohio River, invited Choctaw and Chickasaw leaders to the home of James Robertson, who had settled near present-day Nashville. At first, Ugulayacabé refused, saying that “the Spanish [are] my Whites.” He later agreed to attend to see if Piomingo had ceded any lands to the Americans.

At the meeting, Ugulayacabé wore a costume of scarlet and silver lace and carried a large, crimson umbrella. The Americans gave him personal gifts and several cartloads of goods to distribute to Chickasaw villages. Blount pushed for establishing an American fort and trading post at the mouth of Bear Creek at the Tennessee River on the Mississippi and Alabama border near present-day Waterloo, Alabama. The land had been agreed to in principle at the Hopewell Treaty meeting. Perhaps because of Ugulayacabé’s presence, Piomingo agreed with Ugulayacabé and denied the Americans use of the land. Ugulayacabé argued that the Americans had ‘hard shoes” and, if allowed, “would tread upon [Chickasaw] toes.”

The Spaniards and the Americans continued to court both Piomingo and Ugulayacabé. While each leader had chosen their sides, neither directly dismissed the other’s authority. The Spanish and Americans were forced to continue their gifts to each. Using Chickasaw diplomatic language, Ugulayacabé responded to William Blount’s offer of alliance and requested land cessions. He ended the meeting by stating that if there were a war between Spain and America, his supporters would “stand back and let them fight each other.” According to Native American sources, Blount looked at Ugulayacabé with “evil eyes.“

Ugulayacabé bragged to Spanish envoys that if the Spanish Governor asked, “I will send him Piomingo, who had never given his hands to the Spaniards, I will only have to open my mouth. He will obey because he is one of my warriors.” However, Ugulayacabé did not dismiss Piomingo’s authority directly. Spain granted him a pension of $500 for his friendship. Despite Ugulayacabé’s efforts, Piomingo and the Cherokee did agree to a land cession at Muscle Shoals.

Fort San Fernando de las Barrancas

Also in 1792, Spain deployed a Mississippi River squadron of warships to defend their established forts. With their swivel guns capable of firing 2–3-pound projectiles, the fleet was the most formidable force on the river. By 1795, Ugulayacabé was faced with American settlers and traders streaming into Chickasaw territory and the establishment of an American fort at the edge of Chickasaw land on the north bank of the Ohio River. Due to these pressures, he negotiated a land cession at the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff. After confirming his authority with his Chickasaw followers, he asked Manuel Gayoso, military commander of the Natchez district, to send his fleet to the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff as both a show of force and of Spanish friendship.

Spain had already established a small trading post directly across the Mississippi named Camp Esperanza (Hope). Dutch immigrant Benjamin Fooy ran a trading post granted by the Spanish commander of the encampment. Fooy was a talented linguist who spoke the Chickasaw language and gained the friendship of Indian Nations in his region. The Spanish governor relied upon Fooy’s translation skills in meetings with the Chickasaw. Fooy was more fluent in French than Spanish, and all records of the conferences were translated from Chickasaw to French to Spanish.

Gayoso sent the Spanish Fleet to Camp Esperanza. They put on a show for the Chickasaw observers, firing salutes from their boats as they crossed to the east side of the Mississippi River. On May 30, 1795, Spain raised its flag at Fort San Fernando de las Barrancas. The Spaniards allowed the Scottish firm of Patton, Leslie & Co. to operate a trading post just outside the fort.

Piomingo and his followers were angry, claiming that Ugulayacabé did not have the authority to cede the land. Ugulayacabé then moved his extended family and his property to the Bluffs, a short distance from the fort. The Spaniards granted monthly distributions of goods to Ugulayacabé’s family and the families of Chickasaw leaders Payehuma and William (Tootemastubbe) Colbert. Ugulayacabé’s camp became the first recorded Chickasaw settlement at the future site of Memphis. It was to be short-lived.

Treaty of San Lorenzo

The Treaty of Paris, which formally ended hostilities between the United States and Great Britain, gave the Americans lands stretching from the Atlantic to the Mississippi River and the Northwest Territories, including present-day Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois.

This expanded boundary had the potential to bring conflict between Spain and the United States over the southern border. The Americans sent Revolutionary War general Thomas Pickney to negotiate new borders with Spain. No Indigenous leaders were invited to negotiate the Treaty of San Lorenzo. On October 27, 1795, the United States gained all lands east of the Mississippi above the 31st parallel. The treaty also gave the Americans clear passage of the Mississippi River and the right to pass through Spanish New Orleans without tariffs. Spain abandoned all forts within the ceded territory, including Fort San Fernando de las Barrancas and the Chickasaw Bluffs.

Ugulayacabé’s Response

When word reached the Spanish-allied faction of the Chickasaw, Ugulayacabé was enraged. Ugulayacabé, Payehuma, and 150 followers arrived at Fort San Fernando de las Barrancas in December 1796, demanding to speak with the commandant, Deville Degoutin. Degoutin had already received orders to dismantle and abandon the fort. Benjamin Fooy was summoned as translator.

Ugulayacabé claimed that the Spaniards had lied to him about the need for the fort. They had told him that it was needed to keep the Americans off the Chickasaw Bluffs. Why, he asked,

“Does the Great Father give our lands to the Americans who have no other desire to drive us out and take all our lands as if they were God? We recognize in these [Americans] the cunning of the rattlesnake that caresses the squirrel in order to devour it…Will he [the Spanish King] who is the cause of this look on with indifference and see our blood of which he has been a protector shed by them? … we have seen the treaty…we see that our Father not only abandons us like small animals to the claws of tigers and the jaws of wolves but encourages these same wolves to devour us…If one of us does harm, you will complain to the Americans, who will not distinguish the evil, [but] will blame all of our nation, those of our brothers the Choctaws, or others. Under the pretext of justice, you will oppress us; perhaps whip us as you do your black men…Tell me if I can return to my village to quiet them and to assure our warriors, our children, and our women that what is written of the Americans is false, whether your flag will always fly over our land or the Chickasaw should prepare themselves to die.”

Ugulayacabé, Payehuma, and Benjamin Fooy signed the speech transcription. Ugulayacabé demanded that the commander forward the text to the Spanish Governor, the Baron de Carondelet, in New Orleans. Although the fort’s commandant entreated the Chickasaw to return home until a response was received, Ugulayacabé refused to leave.

A response came quickly. Carondelet began by reminding Ugulayacabé that he has always had the happiness of the “red man” in his heart and assuring him that Spain will never abandon the Chickasaw. Confusing the issue, he says, “The line of demarcation that should separate my states from those of the Americans does not look at or touch the border of the red men.” Adding ominously, “The Americans, our friends, will treat you equally. Consequently, nothing will be lacking to you. You will live in peace with everyone. You will have the option of selling your lands to the Americans or not.” The Spaniards retreated to the west bank of the Mississippi across from the Chickasaw Bluffs with a small armed force and a trading post.

The Results

By early 1797, the Spanish had demolished the fort, and the Americans arrived. Constantly harassed by Ugulayacabé’s followers, the Americans rebuilt the fort and named it Fort Adams. The insistence of Ugulayacabé caused General James Wilkinson and Indian Agent James Robertson to meet with him. Sensing that Ugulayacabé may now be amenable to an alliance with the Americans, Robertson convinced him to travel to Philadelphia to meet with President John Adams. Supplied by Robertson, Ugulayacabé’s party reached Philadelphia. While they might have met Adams, nothing in the official record or Adams’s papers mentions a meeting.

Just as Ugulayacabé feared, American settlers and traders streamed into Chickasaw territory. Any pretext that the Americans had no designs on Chickasaw land vanished when President Thomas Jefferson implemented the “factory” system. This scheme aimed to make the First Nations so indebted to the traders that they would have to sell their land to pay their debts. Piomingo and his followers saw that Ugulayacabé’s words at Fort San Fernando were true.

Fort San Fernando de las Barrancas and Fort Adams were both built in the mosquito-rich area between the Gayoso Bayou and the mouth of the Wolf River at the Mississippi River. The Wolf River’s cut through the bluffs made it a hot, breezeless area. The Americans moved their fort several miles south, near today’s I-55 bridge, and named it Fort Pickering.

Piomingo died in early 1799, not living to see the land grab by the Americans. Ugulayacabé’s name did not appear on any further treaties with the United States. He took part in several land negotiations and even hosted some in his Northern Mississippi village. He died in 1805. According to an American trader and interpreter, he shot himself while suffering from kidney stones.

Ugulayacabé’s negotiations at the Chickasaw Bluffs were the last international diplomatic dialogs on the Chickasaw Bluffs until the 19th century. Some may view Piomingo and Ugulayacabé’s work as a failure. The Americans streamed into their lands, forcing them to sell vast tracts to the United States or individual states. However, their diplomatic prowess and relationships with Spain and the United States kept the Chickasaw from war with these two powerful nations during their lives.

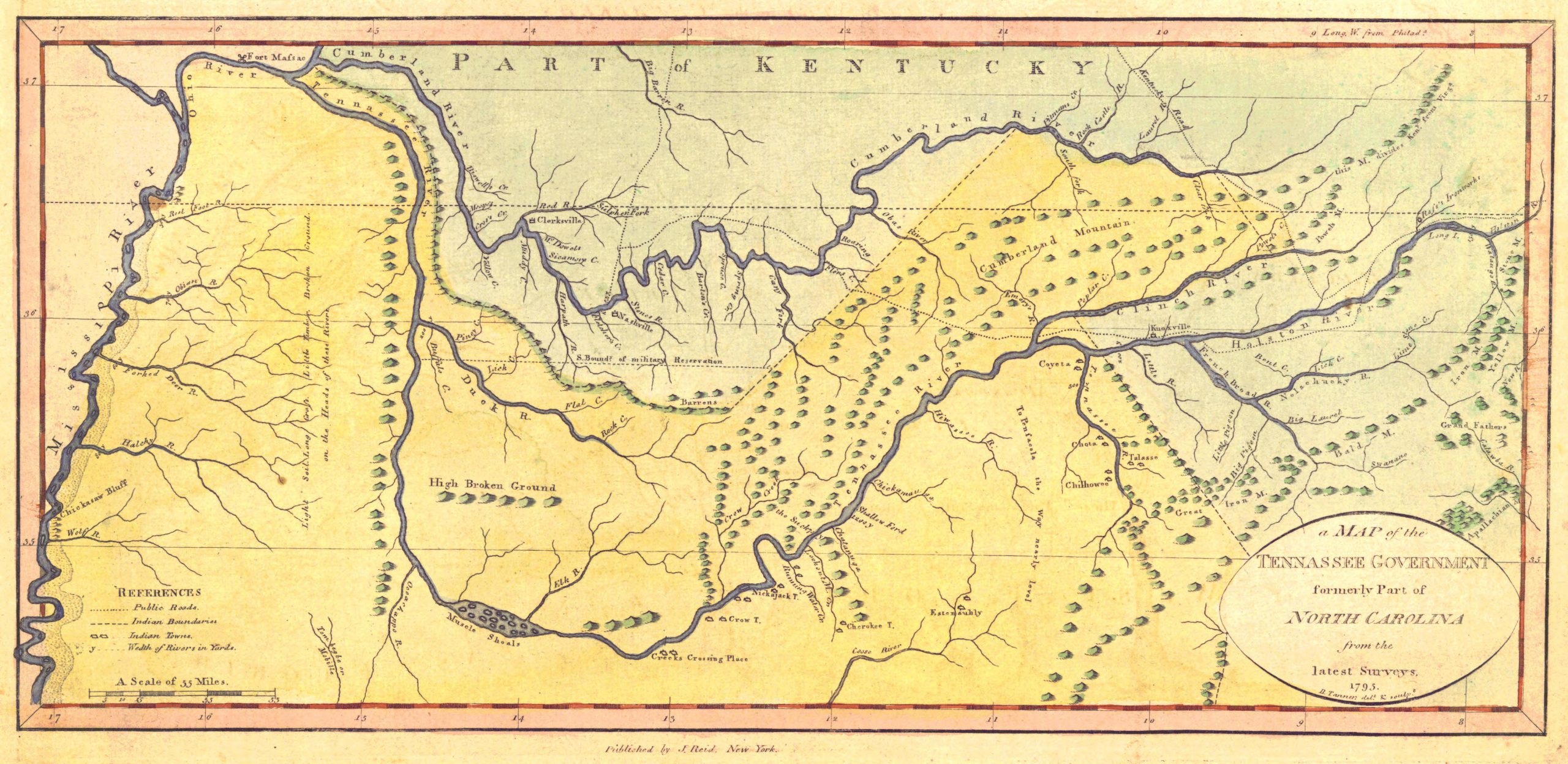

Feature image is Map of the Tennessee Government formerly part of North Carolina from the Latest Surveys, published in Winterbotham’s The American Atlas in 1795. Courtesy of the Birmingham Public Library.

Steve Masler has worked in museums and cultural projects in Memphis since 1980. He is currently the curator for the redesign of permanent exhibits at MoSH.