If you missed part 1 of the history of Playhouse on the Square, you can read it here.

Spring 1969: First Brushes with Celebrity

As anyone who’s cast a show knows, there are times when the ideal dramatis personae does not present itself. Such was the case in the spring of 1969 when the Circuit Players held auditions for The Roar of the Greasepaint-The Smell of the Crowd, a lesser work by Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse who also wrote Stop the World, I Want to Get Off.

The musical had two male principals who had to sing well. Casting fell short, but the show had to go on. Also needed: one African American male responsible for a single killer song and little else. “I was living in the middle of white suburban America at the time,” remembers Jackie Nichols, “and didn’t even know a black actor who could sing, or not. Someone mentioned they had a friend who was an up-and-coming performer, and we should give him a listen. So here we are, waiting for this individual to arrive at my parents’ house, as I was still living at home. The doorbell rings and in walks this striking man wearing what he described as an ‘unborn calfskin jacket.’ After he finished singing for us, and we picked our jaws up off the floor, he said goodbye and gave us his number. Soon after, we found out he would be unavailable as he was about to record an album. Well, that was the closest I ever got to the great Isaac Hayes.”

Building sets in borrowed spaces also proved challenging. This show, staged in Colonial Junior High School’s auditorium, came with very limited rehearsal and tech hours. The students were also required to pay a custodian to remain in the building while it was occupied.

Three days before curtain, the technical director realized they would be set building up until the last minute. But with the players out of both time and money, a slightly unethical plan was hatched. The T.D. hid under the platforms until the custodian locked up the building. In the days before security cameras and alarm systems, he simply crawled out, opened the door and allowed the rest of the crew to work on the set throughout the night.

Greasepaint was only a moderate success, but it made the need for a permanent home more evident.

Fall 1969: A House Becomes a Home

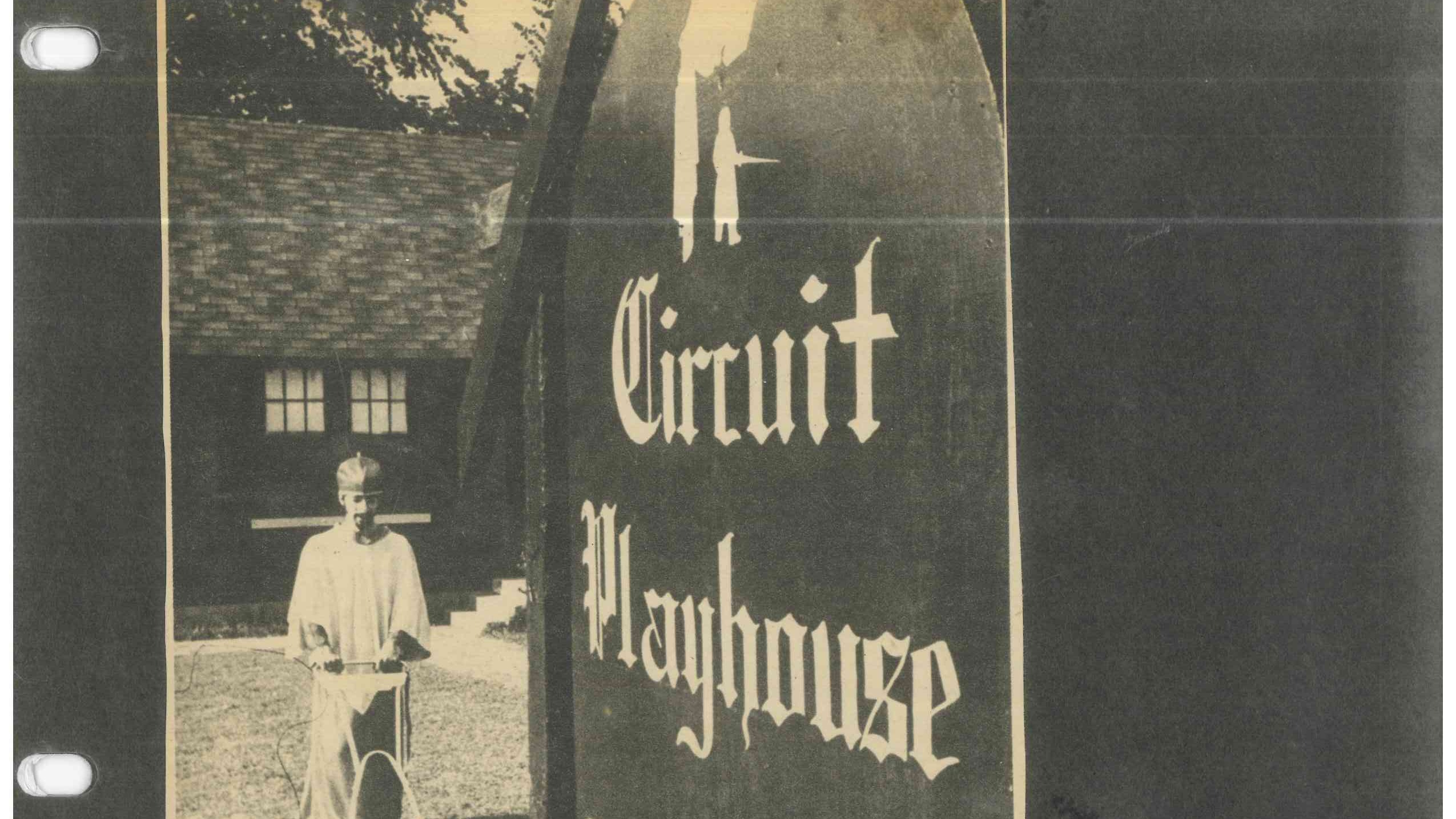

When Front Street Theatre (Memphis’ professional theatre) folded in 1968, it left a theatrical void in the city. So, after closing The Roar of the Greasepaint-The Smell of the Crowd, each member of the Circuit Players pitched in a few bucks to rent a house at the corner of Brister and Walker in the Memphis State area (now University of Memphis), which had been converted into a dance studio. The studio itself was attached to the back of the house and became the acting space. The front of the house contained the lobby, an art gallery, dressing rooms and bathrooms.

Barry Fuller directed our debut effort: a “rock” musical production of The Fanta sticks. The show established us as a bold company from the onset. We were not afraid to challenge the status quo. Then, as now, we were producing shows that were new, stimulating and sometimes controversial. This was a first in Memphis theatre.

The budget for that season was $17,000. And with no consistent source of funding, upcoming bills had to be paid with receipts from the last show or donations from supportive individuals. In the middle of getting the company settled in, Jackie Nichols had to bow out of the new endeavor for three months to complete basic training in the National Guard. Harris Segel served as managing director during his absence.

April 1971: Exposure

After 13 productions in their first home, the Circuit Players were informed that the building had been sold and would become a blood bank. The last production in that space would be memorable in many ways, but perhaps most notably because it featured the first nude scene ever performed on a Memphis stage.

This was not entirely planned. Actor Joe Unger intended to wear a G-string, but at the last minute he discarded his chaste covering, rose from a bath and exited upstage, his naked backside glistening in the stage lights.

Theater critic Edwin Howard remarked: “The scene drew no such gasp as went up from the matinee audience with which I saw the show in New York several years ago.”

The play, The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (a.k.a. Marat/Sade), is a powerful work that addresses political corruption and emotional instability (topics that never seem to go out of date).

Scenic designer Joe Ragey provided one of the most successful conceptual sets the company has ever produced. The audience entered through the front of the “asylum,” weaving through inmates to take their seats. As the show started, cage-like bars lowered, separating them from the performers. A feeling of unease pervaded the audience as the story unfolded only a few feet in front of them. Review comments included “meticulously characterized,” “outstanding,” and “powerful ambience.” The show was sold out for the run and Thursday night performances had to be added.

Christopher Blank is WKNO’s News Director, a frequent contributor to NPR, and moderates conversations about Memphis’s arts and culture community through the station’s Culture Desk Facebook page. He wrote this history of Playhouse on the Square for the theatre’s 50th anniversary.