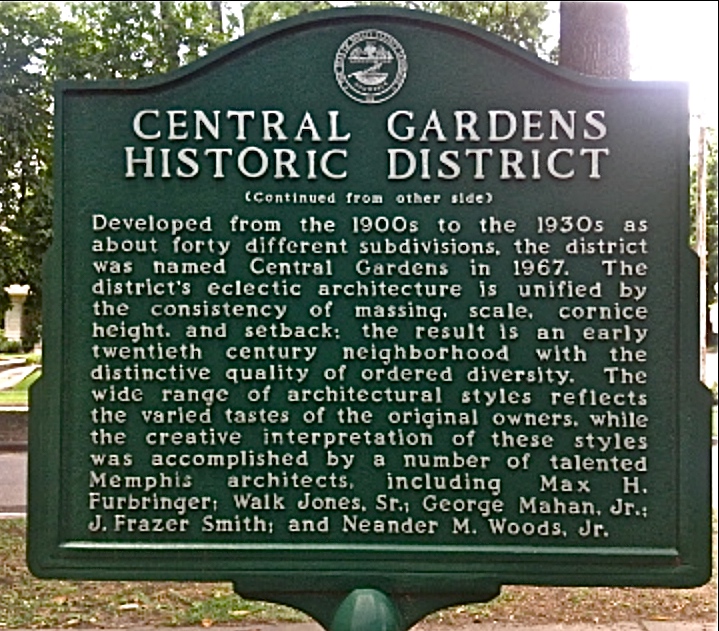

This month, in honor of the upcoming Home and Garden Tour September 10, Central Gardens is exploring the dual efforts in the 1980s and 90s in preserving the neighborhood and upholding its character to today: in 1981 and the work required to place Central Gardens on the National Register of Historic Places; in 1992 and the efforts needed to gain approval by the Memphis Landmarks Commission to establish the neighborhood as a city- and county-recognized historic conservation district.

A version of this article will appear in this month’s Central Gardens Newsletter

Landmarking, Preserving, and Conserving Central Gardens

Landmark. Historic. Preservation. Conservation.

In everyday conversation the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, and sometimes confused. A thorough understanding of each is important to realizing the weight and significance, as well as the legalities, that define and bind our neighborhood and other Memphis neighborhoods under the very important protections that are legislated by such designations.

For the Central Gardens neighborhood, the process started in the late 1970s, roughly ten years after the neighborhood had formed the neighborhood association we know today. By that time the neighborhood had organized to successfully fend off the efforts to bulldoze and pave over the median on Belvedere in 1966-67, and in 1975 to reverse the negative effects that duplexed-zoning was having on the area. The neighborhood had been too late however to stop the development of the two high-density high-rise apartment buildings on Central Avenue just east of Lamar Avenue.

As was the case in the 60s and 70s, the efforts to take the next necessary steps to preserve the neighborhood and its unique character came from more developments, in the form of gas stations and fast-food restaurants, that threatened the neighborhood’s “small-town” integrity.

A “huge undertaking”

“In this (late 1970s) decade, one of the biggest battles was waged by the Central Gardens Association over the sale of the Midwest Dairy property at Union and Belvedere. The association fought for new owners with a more attractive and compatible use for the land, losing bitterly to the existing Shell gas station and food mart. The loss served as another wake up call to the association to become more proactive in its efforts to preserve the integrity of the neighborhood.” (Central Gardens – Stories of a Neighborhood)

The result was the coordinated efforts needed to place Central Gardens on the National Register of Historic Places as a national Historic District. This is, and was, no small task. Nominating just one structure to the National Register requires complete details of the structure’s historical, cultural, as well as architectural significance, and a full inventory of the structure’s key elements and history.

Nominating an entire neighborhood, especially one the size of our Central Gardens, requires the actions of dozens of neighborhood volunteers over the course of a few years. The process here was led by resident and architect Jim Williamson. It started unofficially around 1977 with detailed visual surveys by volunteers of the 1,540 structures in the neighborhood; the nomination form was sent to the Nashville offices of the U.S. Department of the Interior in December of 1980; the final approval of the nomination came back in September of 1982.

“A huge undertaking, the designation protects the neighborhood from changes or encroachment by projects using federal money.” (Stories of a Neighborhood)

Emphasis here should be placed on the phrase “using federal money”; a designation on the National Register does not protect structures from demolition due to neglect or other private interests. Those extra layers of legal protections must come from local county and city governments under state preservation laws, local charters in accordance with city ordinances, and in the form of local recognitions as preservation or conservation districts.

Central Gardens Structures on the National Register, and The Rozelle House

“The Central Gardens Historic District also includes a number of individual landmarks of extraordinary significance, some of which are listed on the National Register. These include Beverly Hall, the E.H. Crump House, the Matthews House (on Willett), the Rozelle-Holliday House, and the First Congregational Church on Watkins.” (Stories of a Neighborhood, and National Register Inventory Form)

Curiously, it took additional time after the 1980 nomination submission for the Rozelle-Holliday House to be added to the National Register. Most accounts declare the clapboard-style cottage house on Harbert Ave to be “probably” the oldest house in the neighborhood (c. early to mid 1850s). And it is likely that additional time was needed to settle a minor debate over whether this or the Clanlo plantation house on Central Ave could lay claim to “Oldest House in Central Gardens.”

Undisputed however is the land where the house sits and its namesake, named for its original ownership and for the very roots of the neighborhood. “The area encompassed by Central Gardens was originally part of the Solomon Rozelle estate. Rozelle settled in Shelby County in 1815 on 1600 acres of wooded wilderness.” (Stories of a Neighborhood)

The Rozelle house was built in either 1852, 1853, or 1855, and according to the official “History of Solomon Rozelle” (written by Yerby Rozelle Holmar, June 14, 1965), Solomon Rozelle died in August, 1856, and was buried in Elmwood Cemetery in the early days of the cemetery. His widow, Mary, “died in August, 1861, a few months after the Civil War started. Union General Quinby and his staff commandeered and occupied the Rozelle home, making it his headquarters.” (“History of Solomon Rozelle”)

Memphis Historic Landmarks, Conservation vs. Preservation, and the UDC

As comforting as national historic landmarking recognition may seem, placement on the National Register of Historic Places has no real legislative protections with regard to demolition due to neglect or various private interests. Developers threatening to demolish historic structures may raise local wrath and outrage, but with the appropriate permits and design plans are more or less free to tear down and rebuild as long as their plans fall within Unified Development Code regulations.

True historic protections must be legislated by city planning, and fall under local ordinance, either county or city. The city and country website says that “The Memphis Landmarks Commission (MLC) was created by Ordinance No. 2276, passed by the Memphis City Council on July 15, 1975 (now codified as Chapter 14-24 of the Memphis Code of Ordinances). The MLC is responsible for preserving and protecting the historic, architectural and cultural landmarks in the City of Memphis. Memphis is one of about 4,000 American cities that have landmarks commissions.” (Shelby County, Memphis Landmarks Commission Responsibilities)

“Requests for such zoning are initiated by property owners in the area who are concerned about maintaining the area’s historic appearance. … Historic districts are established by the final vote of the City Council.”

With this regard the adoption of the updated Unified Development Code – approved unanimously by the Memphis City Council in August 2010 – has been an important step. Prior to the adoption of the UDC, the Landmarks Commission drew a distinction between preservation and conservation districts that in its language could be confusing in actual practice. This confusing terminology went away with the UDC, and today the coding relies on the language within each historic district’s design guidelines to determine what is reviewable.

In 1992 the Central Gardens Neighborhood Association took the steps necessary to apply for a landmarks designation as a historic conservation district. Submitted with that application was the detailed architectural guidelines that the neighborhood had established back in 1980 for their nomination to the National Register (and published in 1981 as the first Central Gardens Handbook).

There were inevitable compromises in the drawing neighborhood boundaries and legislative authority. With anything of such magnitude, which required buy-in by the majority of residents and influential neighborhood institutions, such compromises are made with the greater good in mind; moreover, it is quite possible that the historic conservation district designation would have eluded Central Gardens if not for such give and take.

“In the early 1990s, the Central Gardens Board of Directors fought to have the neighborhood designated as a Historic Conservation District. This designation gives the entire neighborhood the protections of the Historic Guidelines that are applied and governed by the Memphis Landmarks Commission,” said 2017 Association President Kathy Ferguson. “To put it simply, if (certain compromises) would not have been adopted in 1992, none of us … would have the protections now provided under our Historic Guidelines.”

It’s a lesson that other Memphis neighborhoods are being reminded of today. Without historic district and guideline protections, Lea’s Woods might be facing a development well out of line with their guidelines, a development that could have had lasting negative effects. Developments like these are generational – they take decades to correct. Its also a lesson that Midtown’s Cooper-Young neighborhood considers as they begin the same process that the Central Gardens Neighborhood Association initiated twenty-five years ago, a process that has been critical in helping the neighborhood retain its character, charm, and vitality.

————-

2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the Central Gardens Neighborhood Association. And for this year’s newsletters they are celebrating by exploring the history of the neighborhood, taking looks back at important neighborhood decisions, learning about the neighborhood’s infrastructure and the land, and highlighting excerpts from Central Gardens – Stories of a Neighborhood.