Memphis Historic Preservation Part I: The Slums & White Flight

By Mark Fleischer

“We’re late. There’s not much left to save. There has been a great deal of milling around on this thing. There has been very little interest generated among Memphians to preserving the background of their lives.”

~Historian and author Dr. Charles Crawford, in September 1976

Dr. Crawford, speaking with journalist Nickii Elrod of The Commercial Appeal, could not hide his resentment. And depending on one’s perspective, his pessimism could be viewed as just that, pessimism, or an exaggeration — in 1976 there still remained historic structures that had avoided the wrecking ball — or as a true reflection of the bitter mood that hung like a dark cloud over Memphis in the mid-1970s.

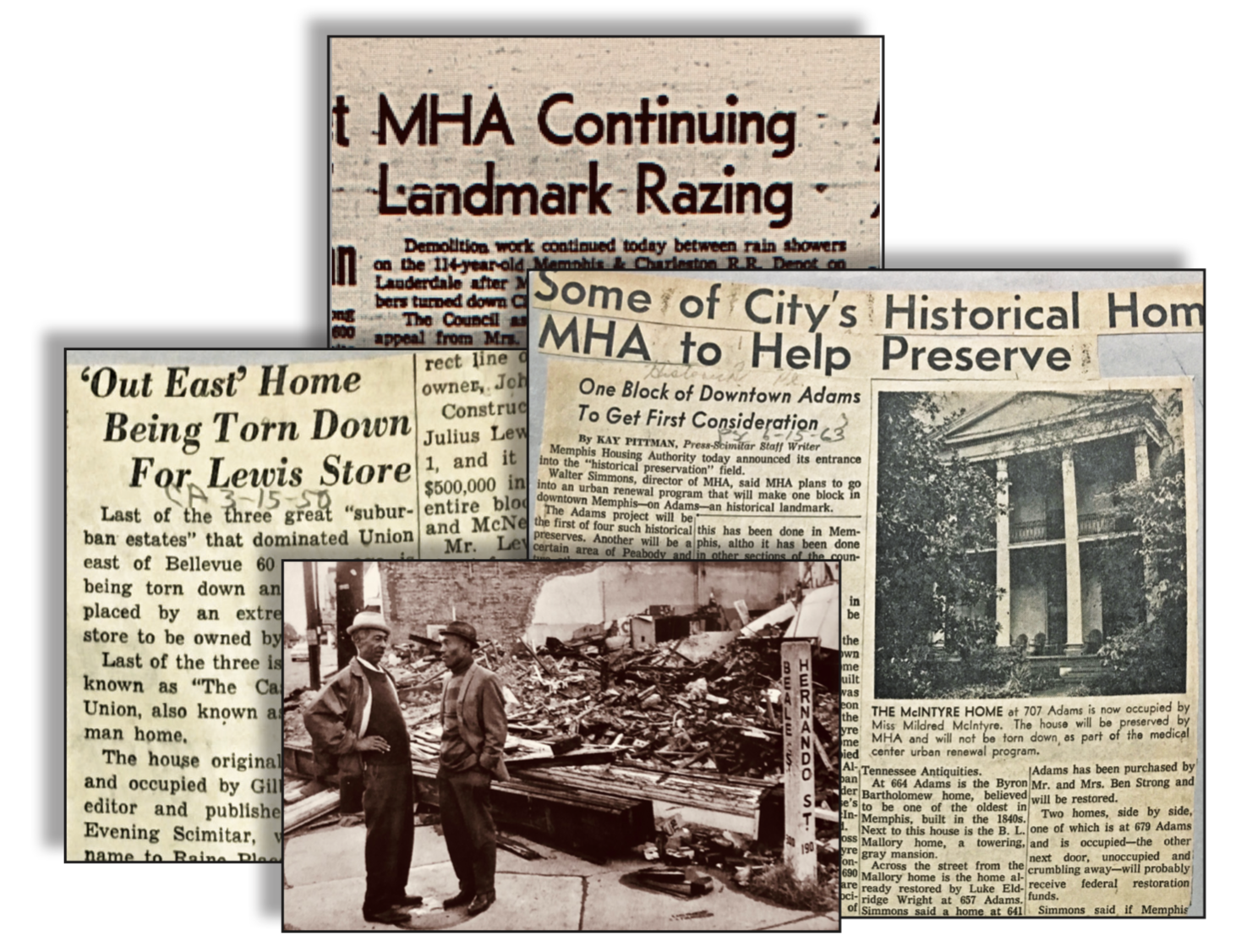

After all, Memphians were witnessing an era in the city from 1957 to 1977 when, under the authorization of Federally-funded slum clearance and urban renewal programs, the Memphis Housing Authority (MHA) demolished roughly 3,000 structures over 560 acres. An era when anything labeled “substandard” within certain planning zones was bulldozed to the ground. An era when so many treasured Memphis structures came tumbling down.

and a photo of urban renewal destruction at the corner of Beale St and Hernando, 1973

(from the The Mississippi Valley Collection)

Gone were downtown train depots and the old Union Station on Calhoun. Gone were all the great downtown movie palaces (in a fluke of urban renewal planning, the Orpheum managed to stay put). Gone was the great Venetian façade of the Memphis Steam Laundry on Jefferson. And from Front Street to out past Lauderdale, hundreds of structures in predominantly African American neighborhoods had been bulldozed or otherwise lost to hosts of suspicious fires or outright arson, or that — in the case of Robert R. Church’s Lauderdale mansion — came down under the false pretexts of a demonstration of fire department equipment.

1976 was noteworthy as the year that the City of Memphis finally formed a new seven-member commission to oversee the preservation and restoration of historic structures. The Memphis Landmarks Commission, voted into being by the Memphis City Council in early ’76, had been assembled at the urging of many preservationists, including Charles W. Crawford, who was appointed to the new commission along with six others. By the fall of that year the commission had a three-year budget to work with, and enough authority to “recommend that structures of historic value be saved by the city, make grants or loans for property restoration and, in some cases, purchase property for resale… (and) designate historic sites and declare certain neighborhoods historic districts.” (Commercial Appeal, 1976)

For some, the commission’s mandate was ten years too late. Congress had passed the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966, and cities such as Charleston, New Orleans, and New York City had gained grassroots momentum and established preservation commissions dedicated to preserving their architectural heritage.

The roots of the preservation movement in Memphis cannot be discussed without revisiting slum clearance, urban renewal and the destruction of Beale Street.

But like many other cities, progress in Memphis was slow to penetrate the conservative doorsteps of City Hall in the efforts to preserve. Conversely, in the 1960s much of both the national and local attention was, to put it simply, focused on cleaning up cities and addressing poverty and inner city slums. This meant widespread slum-clearance programs funded by federal monies, and though originally designed to renew poor neighborhoods, these practices usually resulted in the mass destruction of African American or other minority neighborhoods, which did nothing more than displace generations of families.

The other casualties of these programs were cultural, institutional, historical structures that had suffered years of neglect or were in the path of renewal programs. “To hell with sound timbers (in old, historic houses) from the past,” said an editorial in The Commercial Appeal, knocking the prevailing business attitudes of the early ‘70s, “let’s bring in the bulldozers and get on down the road; there’s money to be made.”

Memphis has done much to preserve its heritage since the Memphis Landmarks Commission was established in 1976, and today ranks consistently in the top ten nationally of cities with structures and districts under landmarks protections. It is something the city can be proud of today. But the roots of the preservation movement in Memphis cannot be discussed without revisiting the spell of the decades-long Boss Crump machine, the Great Depression, slum clearance, urban renewal and the destruction of Beale Street, which in the 1970s had put many Memphians in a bitter, cynical mood with regard to their city’s commitment to historic preservation.

* * * * * *

The Roots of Historic Preservation

The interest in historic preservation began at earnest during the Progressive Era in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1902, when the United States was deep into the booming growth of Industry and the Railroad.

“For nearly 100 years, generations of Charlestonians have been aware of this city’s singular sense of place… Charleston’s unique environment, people, and circumstances contributed to a tradition of preserving and protecting the physical evidence of past generations. Over the past century, Charlestonians have moved from saving individual buildings to entire neighborhoods to maintain the city’s unique sense of place.” (Historic Charleston Foundation)

Charleston began their preservation efforts with private organizations and their acquisitions of key properties starting in 1902. This eventually led to the establishment of the first local ordinance designating a historic district, in Charleston, SC, in 1931. In 1936, New Orleans followed on the heels of Charleston’s efforts when activists’ efforts led to the approval by the New Orleans City Council of the city’s Vieux Carre Commission, which protected the city’s historic French Quarter from encroachment by developers and the wrecking ball.

The Great Depression & Post-War Building

Historic preservation was not on the minds of most Americans in the years after the stock market crash in 1929, when cities across the U.S. faced catastrophic unemployment, homelessness and hunger, with soup lines lining block after block. Housing shortages and overflowing boarding houses gave rise to shanty towns and “Hoovervilles” – homeless villages of sometimes thousands of people, so named for President Hoover, often blamed for the Depression – which sprang up all over the country. While other inner-city neighborhoods, stuck in poverty, deteriorated and turned into slums.

The economy recovered with the onset of World War II, but many soldiers returned home to the same 1930s housing shortages. And as the U.S. transitioned to a post-war, peace-time economy of domestic manufacturing – including the manufacturing of the automobile – cities had to look to outlining rural areas, away from city slums, to meet housing demands.

The Highway System

It was an era of unprecedented growth, and new high-speed road-ways would be needed to move citizens more efficiently to and from their city jobs and to their new, slum-free suburban neighborhoods. This gave us the passage of huge federal bills that would change the look of cities for generations. These included The Housing Act of 1954 and the Interstate Highway Act of 1956. Both acts were designed to promote “speedy, safe transcontinental travel” and growth in American cities, and were widely seen as essential to help big business thrive and in allowing families to achieve the American Dream in pursuit of life, liberty, happiness – and a new car in every driveway.

The legislations had eventual drawbacks. They enabled states to use federal monies to bulldoze neighborhoods under urban renewal and slum-clearance initiatives, and established recommendations as to where routes could be cleared for the building of highways. It makes sense that these routes were chosen in areas already blighted; however, the vast majority of these routes were planned and carried out through neighborhoods of color, further crippling these areas or cutting them off from the rest of the city.

They also crippled the infrastructure of city train and trolley systems as more and more cities catered to the automobile. The new legislation promoted the development of suburban sprawl and redlining (the practice of home-building for and lending to whites only through the use of racial covenant deeds that excluded the black population from the new suburbs), brought on white flight and racially-motivated “slum” clearance policies that gained the nickname “negro removal.” This led to the leveling of entire blocks of downtown neighborhoods in Pittsburgh and Boston; San Francisco and Atlanta; and from Niagara Falls, New York to Beale Street, Memphis.

The highway-building initiatives would eventually threaten historic neighborhoods in New York’s Greenwich Village, SoHo and Midtown, and helped to create the environment that allowed for the sale and demolition of New York’s iconic Pennsylvania Station, from 1963 to 1965.

People from all around the country fought back. Activists, preservationists, the legendary Jane Jacobs, and even First Lady Lady Bird Johnson were leaders in the responses to this destruction, and their collective efforts raised enough public awareness in a push to have Congress pass the National Historic Preservation Act, in 1966.

There had been other efforts by the federal government in their involvement in the preservation movement – the Antiquities Act of 1906, the Historic Sites Act of 1935, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1949 – that were focused on historically-significant sites and structures and that provided preservation assistance. But the 1966 bill became noteworthy in that it finally gave local governments the power to create regulatory historic districts. It also created the National Register of Historic Places, which maintains “the official list of the Nation’s historic places worthy of preservation,” and it placed the register under the authority of the National Parks Service.

* * * * * *

Memphis: Slums & White Flight

The evolution of the preservation movement in Memphis follow generally the same national narratives, from the Great Depression to slum-clearance and post-WWII white flight.

It is a common refrain that the murder of Dr. King in 1968 brought on white flight, urban renewal and the bulldozing of Beale Street. The truth is more complicated than that.

(Memphis Public Libraries)

Memphis was a slum-ridden city in the 1930s. The WPA (Works Progress Administration) survey conducted in 1940 reported that about 50,000 housing units were substandard. The Memphis Housing Authority reported to the public that half of the city’s inhabitants were living in substandard housing . . . 77 percent of the blacks lived in substandard housing . . .

~Robert A. Sigafoos, from his book Cotton Row to Beale Street, page 182

Robert A. Sigafoos, an expert in urban land use and economic development, authored the 1979 book Cotton Row to Beale Street, an exhaustive and data-filled history of business and urban land development in Memphis from its founding to the final years of urban renewal in the late 1970s.

In terms of its recounting of land development in Memphis, it may be the most thorough of its kind locally, impartial, and driven by data. What is striking is that the book reminds us that the seeds of preservation began when ridding the city of its slums became a high priority in the waning years of the Great Depression.

The same WPA report referenced above stated that: “Negro families have had to be contented with inheriting old and nearly worn-out houses left by the white population as it expanded and moved further out into the suburbs.”

Renewal and revitalization became a priority goal of Memphis following World War II. In the late 1930s, there was widespread concern among public and civic leaders over slum conditions in the city. Providing better housing and cleaning up urban decay were deep social and economic concerns evolving out of the Depression period, and considerable momentum was achieved in those years immediately preceding Pearl Harbor. The wars years, however, obscured concern over the plight of thousands of blacks and poor whites living in the city’s slums. If anything, during the war years the existence of any type of housing was considered an asset to house the thousands of war workers and military personnel who migrated into Memphis.

~Cotton Row to Beale Street, page 271

Specifically, during the years before and during WWII, slum housing and blight was concentrated around downtown Memphis, and “other areas in desperate need of rehabilitation were the Orange Mound area, Binghampton, South Memphis near the river, North Memphis, and the Chelsea Avenue area.”

After the war, thousands of GIs returned home looking for work and housing. And a 1946-1947 Annual Report by the Memphis Housing Authority estimated that 13,000 houses in Memphis were substandard, many without running water or toilet facilities, “a menace to the health and safety and morale of the city.” For the city’s black community, the situation was described as desperate, and the Citizens Housing Committee recommended that 5,000 low-rent housing units for blacks be built immediately.

But there were delays. Construction did not resume again until 1953. Why was there this 12-year gap (from 1941 to ’53) in public housing construction considering the magnitude of the substandard housing at that time? It is known that influential private real estate interests feared possible competition of public housing . . . (and) Mr. Crump had grown more and more concerned about Federal government intervention in Memphis local matters.

~Cotton Row to Beale Street, page 272

E.H. “Boss” Crump, it was said, was a one-man inspector of the city’s physical appearance. “I’m the best reporter of bad conditions in Memphis… I note dilapidated houses that need repair, or tearing down… and I report them.”

Mr. Crump died in October 1954, and any prohibitions he may have enforced against Federal intervention into urban renewal projects in Memphis no longer existed. Memphis in 1955 turned to the Federal government for funds to help finance slum clearance programs. The Memphis Housing Authority staff prepared the required “Workable Program” document which outlined what Memphis had already accomplished and what improvements were needed. Once accepted by the Federal government, the MHA was authorized to proceed with urban renewal planning and implementation.

~Cotton Row to Beale Street, page 274

Annexation & Memphis’s White Flight

In 1920, the eastern edge of Memphis’ city limits was at East Parkway and the population was 162,000. By 1930 the new eastern border of the city (along Poplar) was at Goodlett Street and the population was 253,000. In 1950 more annexation allowed for new East Memphis suburban subdivisions, when the population was almost 400,000. And by the early 1960s it extended east to just about the path of the yet-to-be completed Interstate 240, and the population had boomed to almost 500,000.

As the city planners annexed more land east and to the north and to the south, like a slow tidal wave many of the city’s white population moved east, where growth and development moved from downtown west to the suburbs and new downtowns to the east, driven by new automobiles, carrying middle-class whites with them. In its wake were those in poverty and a predominantly-black population, and a downtown that by the early-1970s was a ghost town.

The suburbanization movement started almost immediately on the return of World War II veterans. . . Residential subdivisions (were) developed to serve a huge market of middle and upper middle class people looking for new homes. Aided by FHA and VA financing, thousands of families and individual qualified for home loans which required only modest down payments . . . it is extremely doubtful that the suburbs of most American cities would have expanded so rapidly in the late 1940s and in the 1950s had there been no FHA or VA financing.

~Cotton Row to Beale Street, page 220

Unfortunately this wave was not ridden by African American families. Handcuffed by redlining practices and racial covenant deeds (see below), black families were excluded from home-buying in these newly-developing suburbs.

Redlining

The below redlining map from the 1930s, revealed in 2017 by the National Archives and Records Administration by researchers at the University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab. “It and others like it were used until the late 1960s to designate neighborhoods as safe (blue and green), moderately risky (yellow) or unsafe (red) for mortgage and construction lending.” From “Seeing Red: Mapping 90 years of redlining in Memphis,” by High Ground News in March of 2019.

Racial covenants: These were “a legal tool once commonly used to maintain racial segregation in many of Memphis’ neighborhoods. . . the subdivision restrictive covenant.” (Creme de Memph blogspot)

Meanwhile East Memphis grew into a prosperous (white) suburb, luring Memphians with new developments and the creature comforts of services, retail, grocers and restaurants that made trips to downtown unnecessary.

Clockwise from top-left: plans for a Lowenstein’s East at the new suburban downtown at Poplar and Highland (built in the late 1940s); a brochure for the new Cherry Meadows subdivision at Cherry Road south of Park Ave (built in the early 1950s, new neighborhoods like these were redlined, for whites only); plans for the new Sears store and auto center at Poplar and Perkins (built in 1957); renderings for the new Eastgate shopping center (built in 1964).

Renderings courtesy of Josh Whitehead’s creme de Memph blog.

The post-war era of 1950s and early ’60s East Memphis was the stuff of dreams and memories, the era that many Memphians look back on as the best times of their lives. It was trips to the Pink Palace and Audubon Park, fresh-baked bread from Hart’s Bakery and the Summer Avenue Drive-In.

But it was not for everyone. The wave of prosperity that gave us East Memphis suburbs left behind poor and (majority) black Memphians in divested neighborhoods, and block after city block of crumbling neglect that endangered many of Memphis’ more cherished old structures. Too many would come down before Memphians fought to hold on to what was left. <>

* * * * * *

In Part II, we take a hard look at urban renewal policies that destroyed masses of city blocks, eventually leading to the efforts to create the city’s first preservation commission.

* * * * * *

This article was possible with the help of the resources of the Memphis Room of the Memphis Public Libraries; the digital archives of the Memphis Public Libraries; the Shelby County Register of Deeds; High Ground News; the Creme de Memph blogspot; University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab; Cotton Row to Beale Street (by Robert A. Sigafoos, 1979); Root Shock (by Mindy Thompson Fullilove, 2004); Memphis and the Paradox of Place (by Wanda Rushing, 2009); Beale Street (by Drs. Beverly G. Bond and Janann Sherman, 2006); Good Abode (by Perre Magness, 1983)