A jarring telephone ring at 5:30 AM startled businessman Abe Plough awake. On the other end was Clarence Henochsberg, assistant cashier and popular teller at the American Savings Bank and Trust in downtown Memphis, Tennessee.

Henochsberg had been awake throughout the night and early morning of December 6 and 7, 1926, after he confessed to his wife Jeanette that they were financially ruined. At least, they would be when the bank examiners looked at his books in the morning. The only thing to do, Henochsberg told Jeanette, was to kill himself. She and their two children could survive on his multiple life insurance policies. Jeanette convinced Henochsberg that his friend Abe Plough, a wealthy depositor, would not let things go that far. After all, Plough’s father-in-law, Harry Cohn, was the bank’s president. Jeannette convinced Clarence to call Plough in the morning; he would surely know what to do.

It was a scene echoed years later in the 1946 Christmas classic It’s a Wonderful Life, when on Christmas Eve George Bailey discovers that missing cash – and the greedy and unmerciful miser Mr. Potter – may finally take down the old Building and Loan and send him to ruin.

Clarence Henochsberg passed the anxious night, his mind reeling from hopeless depression to desperate anxiety and, finally, to a plan of sorts. When he startled Plough with his phone call, he had decided what to say. While Plough was not surprised that the early morning call was about the bank’s problems, he could not have suspected that Henochsberg was so deeply involved.

“The examiners will find that my books are $300,000 short ($4,672,659 in 2022 dollars),” Henochsberg told Plough. “The only way to save the bank,” he said, “is for you to give the whole $300,000 to the bank that morning.”

Plough built a successful drug and cosmetics business from scratch and was no stranger to business problems. By 1926, he had a drugstore chain and purchased the St. Joseph Aspirin company. That year, his company had earned $2,900,000 ($45,169,039). Plough took only a moment to respond. “It would be best,” he said, “to bring this before the board of directors. Then, they could raise funds needed to save the bank.”

Henochsberg called Plough again at 7:00 AM. This time, his tone was manic. He insisted that Plough immediately come to his house. Plough again replied that the best course of action would be to present the problem to the board of directors. But Henochsberg was desperate. “If you don’t come over here with the money before eight,” Henochsberg said, “when the bell rings eight, you will know that I am dead.”

With that, Clarence Henochsberg was as good as his word. After leaving a list of all the accounts he remembered misappropriating, Henochsberg killed himself.

Until the week before Henochsberg’s suicide, the American Savings and Trust Bank was a pillar of the Memphis banking community. The bank had fluid capital of $100,000 and a surplus of $123,000, in addition to owning two buildings in Memphis. But on December 2, 1926, bank bookkeeper Rush Parke entered the bank to find state bank examiners making a routine surprise visit. “You can’t check those books yet,” Parke told the examiners, “They have not been posted!” They ignored him and continued their work. Then, knowing the examiners would find a shortage, Parke calmly picked up his hat and coat and told colleagues that he was going across the street for some breakfast.

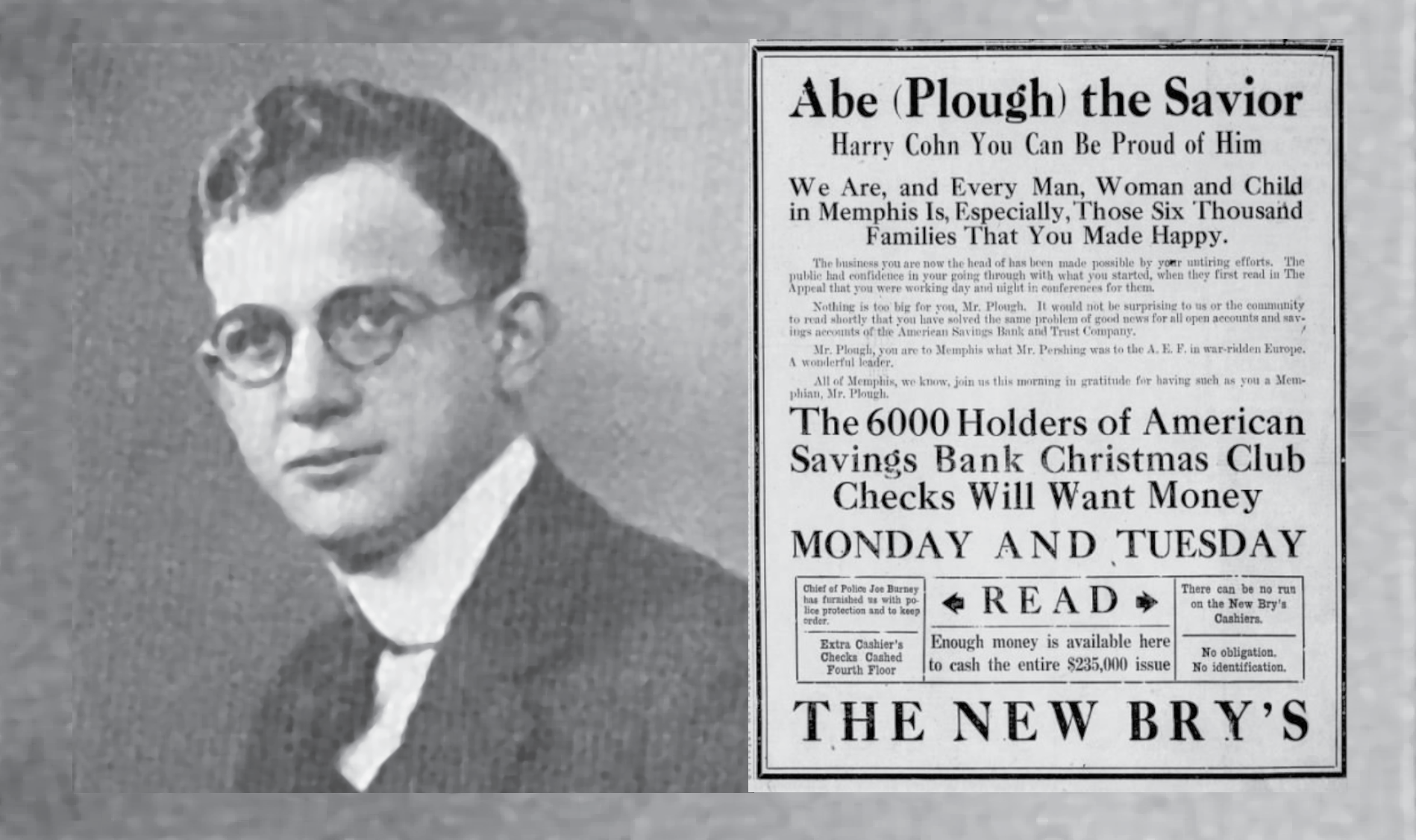

(photo courtesy of Find a Grave: Harry Cohn)

The bank was open for business, and President Harry Cohn was in the lobby, as usual, greeting customers and watching the general commerce of the bank progress. Although Parke was not at his station, Cohn was not concerned until two hours passed. Then, finally, Cohn went to bank examiners and told them of Parke’s unusual absence. They stunned Cohn by responding that Parke’s accounts were short by $100,000 ($1,557,553).

Parke’s disappearance was sudden and complete. A reporter found Parke’s wife at their home on Snowden Avenue. Surrounded by friends and family, a distraught Lottie Parke said that she had dropped her husband off at the bank at 8:30 and hadn’t heard from him since. She told examiners that her husband did not keep papers at home and that she knew very little about his business affairs. However, she knew he had another job keeping books for Jesse Foltz, owner of a Foltz Suburban Markets chain and a bank depositor.

Back at the bank, Harry Cohn was visibly upset. Parke was a model employee. Cohn trusted and even loved all his employees. Still, he told reporters that the bank had sufficient resources to cover the loss even if the $100,000 loss turned out to be accurate. The bank examiners agreed and felt the bank could remain open during the investigation. That was the case until the death of Clarence Henochsberg and the discovery of the additional missing $300,000. Upon learning of the shortage, the bank’s directors requested that the superintendent of state banks take charge of American Savings and Trusts and show that the bank was insolvent.

Friends told reporters that Henochsberg lived beyond his apparent means. “He was obsessed with “pretty and elegant” things,” they said.

Cohn’s trust in his people allowed him to overlook Henochsberg’s purchase of a specially designed Spanish Colonial Revival-style home on Cross Drive in the new Hein Park subdivision, whose unique architecture the Commercial Appeal featured in February 1925. After his death, friends told reporters that Henochsberg lived beyond his apparent means. “He was obsessed with “pretty and elegant” things,” they said. He owned a boat, the Miss Memphis, and had invested in a small steam packet line that had failed. In addition, Henochsberg was a gambler, an exceptionally sharp poker player. Cohn also overlooked the $5,000 fine and 24 hours in jail that Henochsberg received in 1923 after pleading guilty to selling altered war savings stamps.

The bank sent their 6,000 Christmas club account holders a total of $235,000 in combined savings just days before the Parke account shortage was discovered. Christmas clubs were popular savings accounts for working-class families. Throughout the year, people deposited a few dollars each week to save for the holidays. However, as soon as the bank’s shortages were discovered, it moved to stop payment on all Christmas club checks. As a result, 6,000 families were left without the holiday funds they had saved for a year.

Harry Cohn was mortified. He relentlessly paced the lobby while the examiners worked. Abe Plough was deeply concerned about his father-in-law and the thousands of families innocently caught in the bank’s scandal. On December 8, two days after Henochsberg’s suicide, Plough asked the bank examiners if he could give the bank the funds to pay the Christmas club accounts. Instead, he was told that any funds received by the bank would be used to pay all the bank’s debts.

That was when Plough made a plan to save Christmas.

… the Plough group opened their temporary Christmas bank at 120 Madison, ready to cash the Christmas club checks. Plough also convinced local department stores to join the effort…

Plough decided to buy the checks at 100% of their value from the depositors who had received them. However, he knew there was no assurance that the bank would be solvent enough to pay him back. So, Plough offered $175,000 of his own money and convinced fellow business leaders and fellow Jews to contribute as well. Fred Goldsmith and Hardwig Peres agreed to add to the amount. Plough also turned to Lloyd T. Binford, president of Columbia Life Insurance Company, who in 1927 would become the notorious chairman of the Memphis Board of Censors. For the final part of the plan, the Plough group needed a building and was lent the empty Old Exchange Bank at 120 Madison.

On December 9, Rush H. Parke turned himself into Memphis Police. He had been in New Orleans, possibly planning to leave the country, when he heard of Henochsberg’s suicide and decided to return. Arrested and placed in jail, police brought Parke to the bank every morning to show the bank examiners how the scheme worked. The next day, the examiners discovered another shortage of over $20,000 ($335,376.27 in 2022 dollars). Again, Harry Cohn watched while another trusted employee, teller Joseph T. Williams, was taken to jail. Finally, on December 13, police arrested and jailed another trusted employee, Ray Cohn (no relation). Again, 78-year-old Harry Cohn became despondent, watching his “boys” go down.

Investigators caught Ray Cohn due to his manipulation of the accounts of John E. Levy, known as the “Tamale King of Memphis,” and his wife, Claudia Levy. John Levy made a fortune by selling his “hot tamales” from street carts and eventually to restaurants and lunch counters throughout the city. He and his wife each had accounts at the bank that Ray Cohn tended. Mrs. Levy was assured that her account held the substantial amount of $13,834.16 ($215,000 in today’s dollars). However, when the bank examiners inspected the passbook, they found that the account contained only $1,096.91. The book had been sloppily manipulated with scratch outs and number changes throughout. John Levy’s book suffered the same manipulations.

Clarence Saunders, who had built a second fortune after losing Piggly Wiggly, was among the biggest losers. Henochsberg and Parke also ransacked his account. At least one businessman was a willing partner in the embezzlements, Jesse M. Foltz, with whom Parke had a side job. The bank examiners found overdrafts from Foltz’s account of over $100,000.

On December 15, the Plough group opened their temporary Christmas bank at 120 Madison, ready to cash the Christmas club checks. Plough also convinced local department stores to join the effort; Bry’s Department Store, Goldsmith’s Department Store, and Mulford Jewelry Company each offering to cash the checks at total value without identification.

Bry’s proclaimed in an ad, “Abe (Plough) the Savior. Harry Cohn, You Can Be Proud of Him. We Are, and Every Man, Woman and Child in Memphis Is, Especially, Those Six Thousand Families That You Made Happy [sic].” Even Clarence Saunders offered to cash checks at his Clarence Saunders Sole Owner of My Namestores. By December 16, the cashiers at the temporary bank distributed $201,000. It would be a happy Christmas for the Christmas club depositors and merchants in Memphis.

A micro-economy based on the American Bank’s problems arose. Ads appeared offering to buy regular passbooks at less than face value from those hoping to profit when the bank reopened. One ad offered a lot on the corner of Willett and McLemore, which could be paid for by a Christmas club check, the rest to be financed. Naturally, merchants were happy to reimburse customers for their checks and have them shop in their stores.

Meanwhile, the state bank examiners were finding more discrepancies every day. The bank’s debt rose to over $400,000 ($6,707,525) by the end of December, eventually reaching over half-a-million dollars. Harry Cohn stayed at the bank every day, growing noticeably pale and anxious. His family ensured that someone was always with him, although they tried to hide their anxiety about his health. He was too busy and restless to question them.

The morning of December 30, with only two days left in the worst month of the worst year in Harry Cohn’s life, he showed up at the bank at 9:00 AM. He began work with the bank examiners just as he had every morning since the troubles started. Around 9:30, Cohn went down to the basement. After 15 minutes, those watching over Cohn became concerned and asked a bank clerk to go and see if he needed any help. The clerk found the restroom door locked. Hearing no answer to his calls, he ran to get a key. Upon opening the door, he found Harry Cohn slumped on the floor. Stress had taken its toll. Doctors at Baptist Hospital found that he had a heart attack which killed him instantly.

The entire city mourned Harry Cohn. His funeral was held at the Congregation Children of Israel the day after his death. Leaders of the Jewish community and Memphis at large were his pallbearers. Honorary pallbearers included the entire board of the bank, Clarence Saunders, Fred Goldsmith, Noland Fontaine, J.P. Norfleet, several judges, and business luminaries.

When the New Year turned, the state bank examiners pressed ahead with their forensic investigation of the bank’s finances. By February 1927, a grand Jury returned an astounding 84-count joint indictment against Rush Parke and Jesse Folz, which at the time, was the longest criminal indictment in Shelby County history. Also indicted were bank employees Joseph T. Williams, Ray Cohen, and J. Nathan Foote.

During their trials, the defendants attempted to place all the blame on Clarence Henochsberg, who couldn’t answer their claims from the grave. Parke and Folz pled guilty to embezzlement after the bank examiner called their scheme “boobish.” Parke, considered the leader of the hapless two, received a six-year sentence. Folz, receive two to four years. Foote received a sentence of three years. Ray Cohen was the only defendant able to show that he unknowingly made entries into the account of Claudia Levy and John Levy. Henochsberg told him to make the entries from which Cohen made no profit. As a result, he was absolved of all charges.

A new entity, City Savings Bank, took over American Savings Bank and Trust’s debts and credits. With the blessings of the state bank examiner, the directors of the new bank agreed to pay 70% of its debt to passbook holders of the old bank. City Savings Bank opened its doors to the public on March 29, 1927.

In November 1927, Lottie Parke sued for divorce from Rush Parke and filed for a return to her maiden name Lottie Steele. Also in November, John Levy, the Hot Tamale King of Memphis, was shot to death by two assassins who followed him home after a night of gambling at the Antler Club. They took no money and left the scene.

One year after the fall of the American Bank, its successor, City Savings Bank, announced that it would open Christmas accounts in January. They would be headed by Mrs. Elizabeth Allen, the former head of American Bank’s Christmas accounts.

The echoes of suicide reverberate forever to those left behind. The family of Clarence Henochsberg suffered long after the close of the embezzlement trials. Clarence had insurance policies, stock in various companies, a home in Hein Park, and six accounts with American Bank. The proceeds of the insurance policies and the home sale may have been enough to provide for his wife, Jeanette, and their children, Dorothy and Joseph. However, the state bank examiner sued Jeanette, contending that the monies used to buy the life insurance and the house were stolen from the American Savings Bank. Therefore, the bank examiner contended, the family of Clarence Henochsberg should not receive any of the proceeds. In 1930, the case was appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which found in favor of the State.

(source, Find a Grave, Joseph Henochsberg Brooks)

The Henochsbergs were left with next to nothing. That year, Jeanette took a job in retail sales and moved in with her mother on North Willett Street, where she was still living in 1940 with her son Joseph, her brother, and her mother. Joseph was 22 years old and worked in an insurance office. Joseph legally changed his name to Joseph Brooks, Jeanette’s maiden name. In 1945, Jeannette moved to St. Louis and married Samuel Jacobs, who died three years later. She married her third husband, Milton Cohen, and lived happily with him until he died in 1976. Jeannette died on December 23, 1986.

Abe Plough’s success in business only grew throughout the years. So did his belief in giving. He was no Mr. Potter. Plough gave millions to the community throughout his life, often anonymously and so often that some fundraisers in Memphis called him “Mr. Anonymous.” His work saving the Christmas club was raised to mythical status in 1939 in T.H. Alexander’s article for The Rotarian magazine entitled, “The Gifts of the Magi.” Alexander dramatically portrayed Plough as appearing at the bank, surrounded by 6,000 people, pushing his way through the crowd to find his father-in-law arguing with the bank examiner and dropping dead on the spot. It was printed in the Commercial Appeal on December 10, 1939. Nationally syndicated columnist Walter Winchell picked up the story, and newspapers across the country reprinted it on Christmas day for several years.

Plough died at the age of 92 in 1984. After his death, his charitable works continued with the Plough Foundation, which he had founded in 1960. The foundation followed Plough’s belief that “You do the greatest good when you help the greatest number of people.” He is buried in Temple Israel Cemetery, as are other participants in this drama – Fred Goldsmith, Hardwig Peres, Harry Cohn, and yes, Clarence Henochsberg.

StoryBoard is honored to publish Steve Masler’s historical works. Steve has been involved in museums and cultural programs in Memphis since 1980.