A long-lost study of the Mississippi Delta reveals the source of the blues

By Jonathan Frey, for Chapter16.org

In the early 1940s, Fisk University scholars undertook a multi-faceted sociological study of Coahoma County, Mississippi. The project, known as the Coahoma Study, contained far-reaching revelations about the Mississippi Delta region and its culture, particularly its African American musical traditions; yet, remarkably, its results lay unpublished for over 60 years.

In 2005, editors Robert Gordon and Bruce Nemerov compiled the material from this extraordinary study in Lost Delta Found, published by Vanderbilt University Press. The book was recognized by The Blues Foundation in 2019 as a Classic of Blues Literature and has been reissued this year in paperback.

Lost Delta Found: Rediscovering the Fisk University-Library of Congress Coahoma County Study, 1941-1942

By John W. Work, Lewis Wade Jones, and Samuel C. Adams, Jr., edited by Robert Gordon and Bruce Nemerov

Vanderbilt University Press

344 pages

$18.95

The original stimulus for the Coahoma Study was an event in a totally different Mississippi county 200 miles south. In 1940, an accidental fire at the Rhythm Club in Natchez (Adams County) took more than 200 lives. John Work III, a musicology professor at Fisk University, proposed to examine the cultural ramifications of the calamity a year later, with the goal of capturing the expected folk memorials. Owing to the exigencies of time and resources, the original proposal instead evolved into a series of research field trips, in collaboration with famed Library of Congress folklorist Alan Lomax, focusing on Coahoma County.

This new focus was fortuitous. The broader scope produced a rich trove of material, including an overview of the Delta region by Fisk sociologist Lewis Jones; John Work’s untitled manuscript of sociological and musical findings; Work’s transcriptions of more than 150 songs; and Fisk graduate student Samuel Adams’ master’s thesis, which drew on a survey of 100 plantation families in the region.

As the editors’ introduction to Lost Delta Found notes, “John Work’s interest in folk music sparked one of the earliest, most important, and comprehensive studies of folk music culture in the United States.” The ensuing research documented the genesis of the blues, a genre with a profound and enduring influence on American popular music. The study identified some of the earliest blues musicians, tracing their music to post-Civil War African American life, especially among Mississippi sharecroppers and levee muleskinners. The study revealed African American contributions to developing the Delta economically, as well.

Owing to personality conflicts among the investigators and the demands of World War II (both Lomax and Adams were drafted), the Coahoma Study discoveries were never published in unified form, though the Library of Congress released field recordings of the Delta bluesmen as early as 1942. In 1993, more than 50 years after the fact, Alan Lomax would incorporate his and others’ Coahoma observations in his award-winning opus, The Land Where the Blues Began. Meanwhile, the notes, manuscripts, and transcriptions went separate ways, each getting lost in different places, some lost permanently to fire (but thankfully not before being microfilmed). The Jones and Work manuscripts were rediscovered accidentally by Lost Delta Found co-editor Gordon, tucked in the back of a file cabinet at the Alan Lomax Archives at Hunter College.

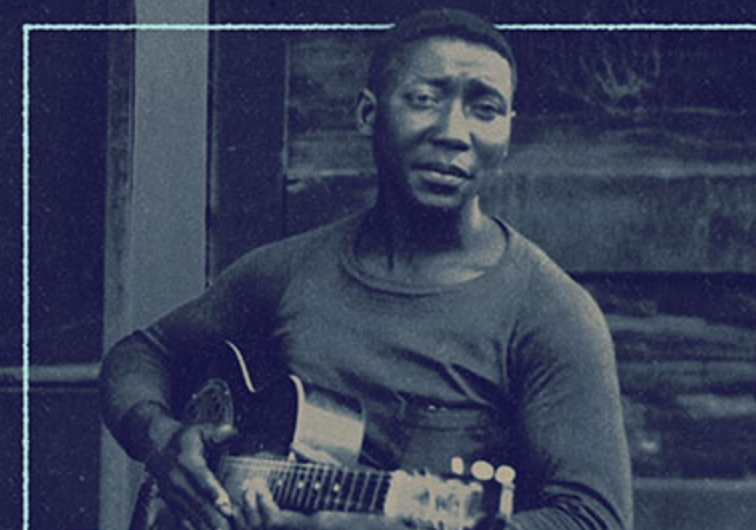

Perhaps the most famous outcome of the study relates to the discovery of one McKinley Morganfield, a 29-year-old sharecropper, musician, and singer, soon to be known worldwide as Muddy Waters. As Lomax would describe it in Where the Blues Began, this “session has become a holy occasion in the minds of blues lovers, so much written-about and discussed that young blues scholars seem to know more about what went on than I do.” Indeed, two of the cuts recorded at that time were to launch Waters’ career, resulting in his relocation to Chicago where he became perhaps the best representative of that city’s blues sound.

That famed Waters session is not without controversy, however. Work conducted the interview with Waters, who during the recorded session clearly identified himself as Muddy Water, singular. However, the liner notes to the Library of Congress recordings released a year later identify Waters in the more commonly known plural form. The editors of Lost Delta Found credit this discrepancy to a typographical error of Lomax’s, suggesting that it established Morganfield’s ultimate professional name, now known the world over.

That odd fluke befits a project with such a complicated history — one that wandered far from its initial focus and then saw much of its original material lost or unrecognized for 60 years. Music lovers and scholars of Delta life can only be grateful for its rediscovery and belated recognition as an essential contribution to our understanding of this piece of American culture.

Jonathan Frey lives in Knoxville and writes about music and books