Clayborn Reborn

From the Archives: Originally published in May, 2019

By Margot Payne

Sometimes it takes decay, or the near total loss of a tangible piece of history, to remind us of its beauty and importance. In April of 2019, the whole world watched in horror as flames engulfed Notre Dame. The cathedral has stood in the middle of Paris for 856 years, an enduring witness to the European Renaissance, the French Revolution, and two World Wars.

French President Emmanuel Macron described Notre Dame as “our history… the epicenter of our lives,” and vowed it would be rebuilt.

France has done it before. The structure didn’t fare well during the Revolution, and continued to decay well into the 19th century. The crumbling church and its Gothic architecture had fallen out of favor, but writer Victor Hugo saw Notre Dame as an essential part of French cultural history. To advocate for its restoration, Hugo published his novel “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” in 1831. The dilapidated church became both the backdrop and a central character in the story, personified by its deformed bell-ringer, Quasimodo. Hugo’s hugely popular story captured the history and importance of the structure, and breathed new life into it, kicking off a major restoration campaign in 1844.

StoryBoard Memphis sat down with Anasa Troutman, Executive Director of Clayborn Temple, just a week after Notre Dame went up in flames. The 127 year old Memphis landmark was shuttered in 1999, and like Notre Dame, fell into serious disrepair. After its purchase in 2015, the building reopened under Clayborn Reborn, a nonprofit dedicated to restoring the building, honoring its history, and making it an active part of the community once again.

Troutman originally came to Memphis to co-write and produce Union: The Musical. Initially performed for the MLK50 commemorations held in Memphis last year, the production tells the story of Clayborn Temple as the home base of the Sanitation Workers’ Strike of 1968. Like Victor Hugo, “we did Union: The Musical because we wanted to tell a compelling story to get people interested in this place,” Troutman says. “To understand why the place is so important, and why the sanitation workers are so important.” The successful production now tours nationally, with the goal of community healing through the powerful and universal story of Clayborn’s past.

The story of Clayborn Temple goes beyond its role in the Sanitation Workers’ Strike that brought Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to Memphis fifty-one years ago. As Troutman explains, “The whole story, from the first day it opened in 1892, is a story about race and class.”

A Jewel in the Crown

Originally built as Second Presbyterian Church, the rare Romanesque Revival structure was once the largest church building south of the Ohio River. The white congregation remained at the corner of Hernando and Pontotoc for over fifty years, as the Great Migration brought more and more blacks to downtown Memphis. By 1949, like so many white urban churches across the South, Second Pres retreated to the suburbs. That same year, the building was purchased by the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), and renamed Clayborn Temple after AME Bishop Jim Clayborn. The building became a safe haven for organizers and advocates for racial equality in Memphis and the Mid-South, most notably during the 1968 strike.

“It didn’t happen in a vacuum,” explains Troutman. “It’s a continuum of a story about race and class in this neighborhood. How black Memphis and poor Memphis was treated, and created, in this neighborhood, with this building sitting here the whole time…I see the Sanitation Worker’s Strike as a jewel in the crown that is the story of this place. It’s the entry point for a lot of people, saying ‘Ooh, look at that shiny red ruby in the middle of that crown.’ But really, if you look at the intricacies of the entire crown and all that detail, this whole building’s history is about race and class, and my highest hope is that we can continue that story in a way that actually resolves, if not creates a different relationship with, race and class.”

Whole Truths

Troutman admits that this is a difficult task. Discussions of race and class are uncomfortable dialogs for any community. Beyond community engagement or historic preservation, the foremost mission of Clayborn Reborn is community healing, and part of that mission includes telling the whole story. “We can’t just tell the part of the story that’s exciting or fulfilling,” Troutman explains. “We need to tell the whole story, even the parts that are painful or embarrassing or shameful. We need to tell the story without the intention to shame or embarrass or hurt, but with just an intention of integrity of the story in telling the whole truth. And that’s really hard, especially when you’re talking about something that continues to be a source of pain for this city.”

Equally difficult is getting to the whole, harder truths themselves. Troutman recalls a long conversation with Reverend James Lawson, who was so integral to the events and the retellings of the events of 1968. “He was saying to us how wrong the story is told in public, how much of the story is missing, how much of what actually happened and were actual motivations and actual events just are not conveyed at all or are told totally wrong. Our work with him needs to be to unearth the parts of the story that people don’t know.”

Race and Class, Hope and Despair

Troutman and the Clayborn team strive not only to tell the complete story of Clayborn Temple, but to successfully add it to the narrative of the greater Civil Rights Movement in Memphis. For many, the story begins and ends with Dr. King’s assassination on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, but that summation is grossly incomplete. “It is very difficult for this not to be a place that leaves you feeling despair,” Troutman says. “I’m really interested in figuring out how we help give that story a different perspective, or at least help people see that the thing that’s most important about Martin Luther King is not where he died, but why he came here in the first place.” Inspired by their bravery and the powerful grassroots movement they created, King came to Memphis to support the sanitation workers. “I think that if people knew that, even with the hopelessness that you can feel in a moment when you’re looking at that so closely, you can still leave this place feeling inspired and engaged and ready to move forward.”

In this vein, Troutman hopes to present the pain associated with Clayborn alongside the rich culture and inspiring people and stories that came from it. As she explains, “if you just tell the story of the despair, then you don’t know how to move forward. If you tell the story of what happened outside of the context of the culture… you don’t understand the power of culture that helps you liberate yourself when you’re in the shackle.”

As the caretaker of this National Register listed property and newly minted National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Troutman aims to do both. “The opportunity that we have here is to be able to tell the history and express the culture at the same time. You can feel the despair and the hope at once. You can feel the truth of the story and the truth of the future at once. That to me is the most important thing that we can do here that helps complete the story that is so eloquently being told at the [National Civil Rights] Museum down the street.”

Canonizing the Story

“You walk past a church and look at the windows and think they’ve always looked that way, but there’s a story in every one of those changes.”

Anasa Troutman, Executive Director of Clayborn Temple

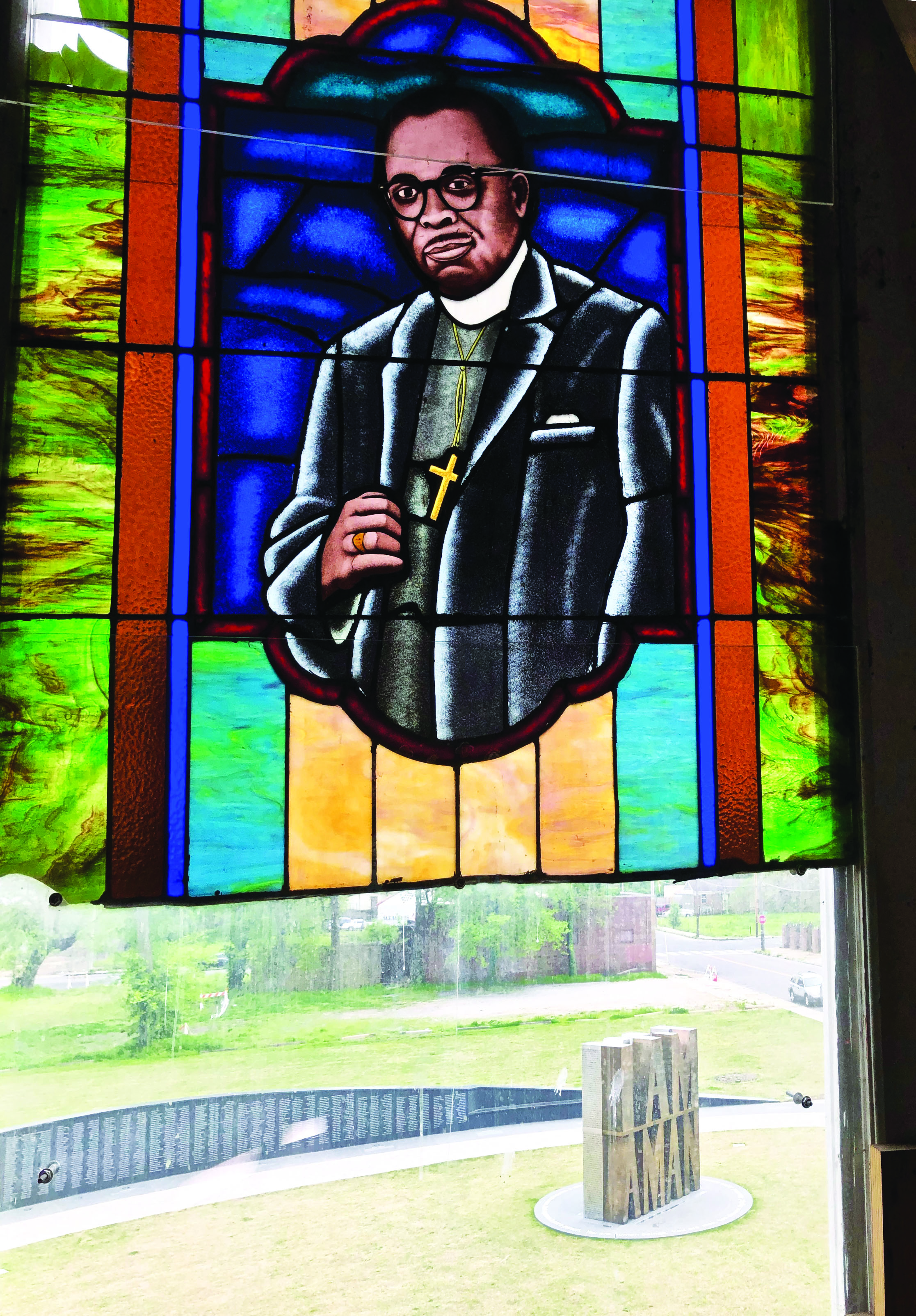

Troutman wants these stories of hope and despair to come alive both in the programming of the space and in the restoration of the building. “[The stories have] to be embedded in every inch of the restoration process,” she says, and the reimagining of Clayborn’s stained glass windows will be the primary place where the full story is told.

After decades of neglect, Clayborn’s once grand stained glass windows are in varying states of disrepair. While some remain intact, a truss failure caused part of the roof to cave in, buckling the walls and crushing many of the window jambs. These structural issues must be addressed before windows can be restored, or in other cases, reinvented. Each presents a different preservation issue depending on its exposure to the weight of the building and the roof.

The Clayborn team studied historic photographs to determine the evolution of each piece of stained glass installed on the building. Based on the photographic evidence, it’s clear that the windows have changed drastically overtime. Some moved east with Second Pres in 1949, while others were damaged in 1968 when police threw canisters of tear gas through them and into the sanctuary. As church leadership changed and different restoration campaigns were initiated, the glass reflected those changes. “Right now we’re trying to piece that story together so we can figure out which parts we’re going keep and what parts we can replace with the story we want to tell,” explains Troutman. “You walk past a church and look at the windows and think they’ve always looked that way, but there’s a story in every one of those changes.”

Because so much of the original fabric is missing, there is an opportunity to fill in the blank spaces with more modern images that tell the story of the Sanitation Workers’ Strike. “The decision to not go with traditional church imagery is not just about telling the story,’ Troutman says. “It’s also about canonizing the story as part of our sacred history that deserves to be exalted and explored and expressed through stained glass in a sacred space.”

Clayborn is committed to working with local artists and community members to create the new imagery. “To be up there it needs to be beautiful, it needs to be informative, but most of all it needs to be in integrity with the values of this organization, which is about extending the work of the sanitation workers,” Troutman explains. “It has to be sensitive to race, it has to be sensitive to class, and it has to be something about dignity and humanity and the future… We can find that wisdom in this neighborhood. On this block. We believe there’s wisdom in all of us, and there’s no greater power than being able to tell your own story.”

While the exact images are still undefined and the final storyline must be approved through the historic preservation grant process, the technique of transferring art to glass is set. The new panes will use the color palate of the existing stained glass, so the lighting and color impact will remain the same inside the sanctuary. The resulting look will be cohesive with the traditional patterns and images, but share a more complete history of the sacred space. One idea is to replace the panes broken by the tear gas canisters with new glass that still appears shattered, or is simply blackened, as not to erase the visual history that remains from its most significant era.

Sacred Spaces

Once the restoration is complete, the story of Clayborn Temple will carry over from the windows into the programming and interpretation of the historic site. The sanctuary space will remain open with modular furniture to suit any event, production, or meeting. Beyond a state-of-the-art performance space, modern bathrooms, and ADA accessibility, nothing is set in stone, but the community is constantly generating ideas for how best to tell the story of the past while also planning for the future. As Troutman explains, “We’re talking about all kinds of things to do in the building, but it all has to stem from the story of the place and it all has to lead to the story that we want to create for this community and for the city.”

For example, it was at Clayborn that the iconic “I Am a Man” signs were distributed in 1968. They were printed in the basement using a printing press that belonged to the pastor. While Troutman is having trouble locating the original printing press, there are discussions to recreate the set up and build a printing trade program in the basement. Neighborhood kids could learn how to build a business out of the trade and be employed to create new “I Am A Man” signs to be sold as mementos. Troutman also recalls how the wives of the sanitation workers cooked for them twice a day onsite. “They made breakfast and they made lunch,” she says. “And how do we tell that story in a way that’s compelling and also supports the future that we want to have? We’ve talked about having a test kitchen restaurant in the basement and being connected to local food.”

The Hunchback of Clayborn Temple

“Even in our brokenness we can find beauty and a reason to keep going,

Anasa Troutman, Executive Director of Clayborn Temple

find something to build on.”

Throughout the entire community engagement, research, and planning process, Clayborn Temple has remained open to the public. Phase II of the renovation is slated to begin in June, and after some more fundraising, Clayborn is hoping to only be closed to the public for 14 months.

To view Clayborn Temple in its pre-revitalized state is a powerful thing. It’s rough around the edges, but the peeling plaster walls and dusty woodwork reveal all that they have witnessed. The open sanctuary feels sacred and alive. “When I go out there, I see beauty,” says Troutman, “I don’t see decay. I think that it’s a metaphor for our city and for our country. Even in our brokenness we can find beauty and a reason to keep going, find something to build on. That’s why the building remains open, because we want people to come and experience it. To me, the people who walk in here and can’t see [the beauty], are people who avoid pain and who avoid conflict and who avoid ugliness and they will never get to their joy because you cannot circumvent life. You cannot circumvent hurt. You cannot circumvent difficulty. You can’t do it. And when you don’t look at this place and see the beauty in it, it means to me that you have not figured out life. Is that too far of a leap? I don’t think so.”

The themes of finding beauty in the decay, and hope in despair, can be found throughout Clayborn Temple, in both its current raw form and plans for its future restoration. Because of the diligent community work and collaborative design process of Clayborn Reborn, this once crumbling church doesn’t need a Victor Hugo or a Quasimodo bring its stories to life; just a steady leader like Anasa Troutman who is willing to listen. “One of the only things that gave me pause about doing this work was me acknowledging that this is not my story,” Troutman says. “I’m not from here, my parents aren’t from here, my grandparents aren’t from here. I don’t have a story about [this building]. I want to be a good shepherd of the stories and be responsible and respectful and worthy of telling them. I’m willing to be accountable to the people in this town, I really am. I feel like my work depends on it.” <>

Feature photo courtesy Clayborn Temple