Candacy Taylor documents the revolutionary guide that helped black travelers navigate a segregated America

Originally published February, 2020.

By Kim Green, for Chapter16.org

In the introduction to Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America, Candacy Taylor shares a story told to her by her stepfather, Ron Burford. A sheriff pulled over Burford’s father and was suddenly in the window asking frightening questions. As the little boy sat rigid with fear in the back seat, his dad pretended that the shiny 1953 Chevy belonged to his employer and introduced his wife as the maid and Ron as her son. The detail that finally defused the officer was a chauffeur’s cap hanging in the back seat: “a ruse, a prop — a lifesaver.”

Burford had never noticed it before. But after that day, he started to see those black caps everywhere, “strategically placed, like unarmed weapons, in the back of nearly every black man’s car.”

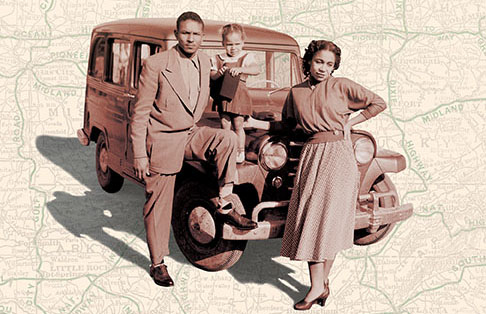

It’s a powerful opening scene for Taylor’s cultural history of the Green Book, an extraordinary guide published from 1936 to 1967 to help black travelers find places to safely sleep, eat, shop, or service their vehicles. Several such guides existed, but the Green Book, created by a postal worker from Harlem named Victor Hugo Green, had the longest run and the highest circulation.

In the first chapter, titled “Driving While Black,” Taylor makes it clear why such a guide was vital. As anyone sentient in America surely knows, black travelers in the Jim Crow era faced uncertainty and humiliation — and often far worse. But knowing isn’t really knowing for those of us who haven’t lived the experience. Which is why Overground Railroad is more than a chronicle of the Green Book itself; it’s a blunt-force reality check to anyone who refuses to grasp that the freedom of the open road — and the American dream itself — has not historically been open to all Americans.

Black Lives Matter Files: Revisiting StoryBoard and partner archives to understand the roots of unrest. “… a riot is the language of the unheard,” said Dr. King in 1967. More importantly, “what is it that America has failed to hear?” ~Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 1967*

Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America

By Candacy Taylor

Abrams Press

360 pages

$35.00

Taylor underscores that fact with recollections like Burford’s and descriptions of the ugly realities black motorists faced, including all-white “sundown towns” that barred them from the city limits after dark, the refusal of basic services at many white-owned businesses, and national parks with few (or no) facilities for black vacationers. Even Coca-Cola machines were labeled for whites only.

Despite these obstacles, black Americans took to the road, armed with strategies to stay safe: aliases and supporting props, bedding, ice chests full of food and drinks, portable privies, gas cans — and often the Green Book. “It represented the fundamental optimism of a race of people facing tyranny and terrorism,” writes Taylor. “When I first saw it, I was struck that something so simple, and so practical, could be so powerful. Not only did it show black travelers where they could go, but it was also a compelling marketing tool that supported black-owned businesses and celebrated black self-sufficiency and entrepreneurship.” The guide may not have been overtly political, but as a survival tool, it was quietly subversive.

With Overground Railroad, Taylor — an author, photographer, and cultural documentarian — has created a compelling and informative history, as well as a beautiful volume filled with images from various editions of the Green Book, archival photos of the people and places she highlights, and photographs she took of the surviving Green Book businesses. Those stories and images will carry readers along on Taylor’s own journey, which is both spatial and philosophical: “With the Green Book in the rear view mirror,” she writes, “I saw America for what it is, not what it imagines itself or even aspires to be.”

Readers, too, will come to know this America, if they don’t already. Each chapter highlights a different era of the guide and touches on a related theme in U.S. history, such as the Great Migration and the civil rights era. The Route 66 chapter will likely complicate any retro-postcard nostalgia you may harbor about that storied road — with sections on Fantastic Caverns, a Klan-operated tourist site in Missouri where cross burnings were held, and on the massacre of black citizens in Tulsa’s Greenwood District, once considered the “Black Wall Street.”

Taylor finishes on a note of melancholic loss, overlaid with resolute pragmatism. One unintended consequence of integration, she laments, was that many black-owned businesses listed in the Green Book struggled to survive. But some remain, and Taylor has assembled a marvelous state-by-state list of historic Green Book structures and even a few businesses still in operation. Patronize those and other minority businesses, she exhorts, in her “What We Can Do” section at the end of the book. Other constructive suggestions include mentoring a kid from a vulnerable community, pressuring local politicians to change policies that lead to mass incarceration, and reading Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow. In offering tangible actions readers can take, Taylor has created a valuable document which, like the Green Book itself, serves as a bittersweet handbook of resilience in the face of injustice.

Kim Green is a Nashville writer and public radio producer, a licensed pilot and flight instructor, and the editor of PursuitMag, a magazine for private investigators.

*During his 1967 speech “The Other America,” Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said that “a riot is the language of the unheard.” In 2020, in direct contrast to those summers generations ago, evidence suggests that much of the rioting we are seeing today is not being caused by protesters, but by factions of groups exploiting the moment. Multiple reports tell us that the majority of the protesters, black, brown and white, are practicing nonviolent marches and protests.

However, what Dr. King said in 1967 remains true today. It begs the question: As an equitable and just society, what kind of progress have we made in the last 50 years?

I’m still convinced that nonviolence is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom and justice. . . . I think America must see that riots do not develop out of thin air. . . . But in the final analysis, a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality, and humanity. And so in a real sense our nation’s summers of riots are caused by our nation’s winters of delay. And as long as America postpones justice, we stand in the position of having these recurrences of violence and riots over and over again. Social justice and progress are the absolute guarantors of riot prevention.

~Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. From his 1967 speech “The Other America”