A MEMPHIS CONNECTION – INSPIRED by WILLIE BEARDEN

By Joe Lowry

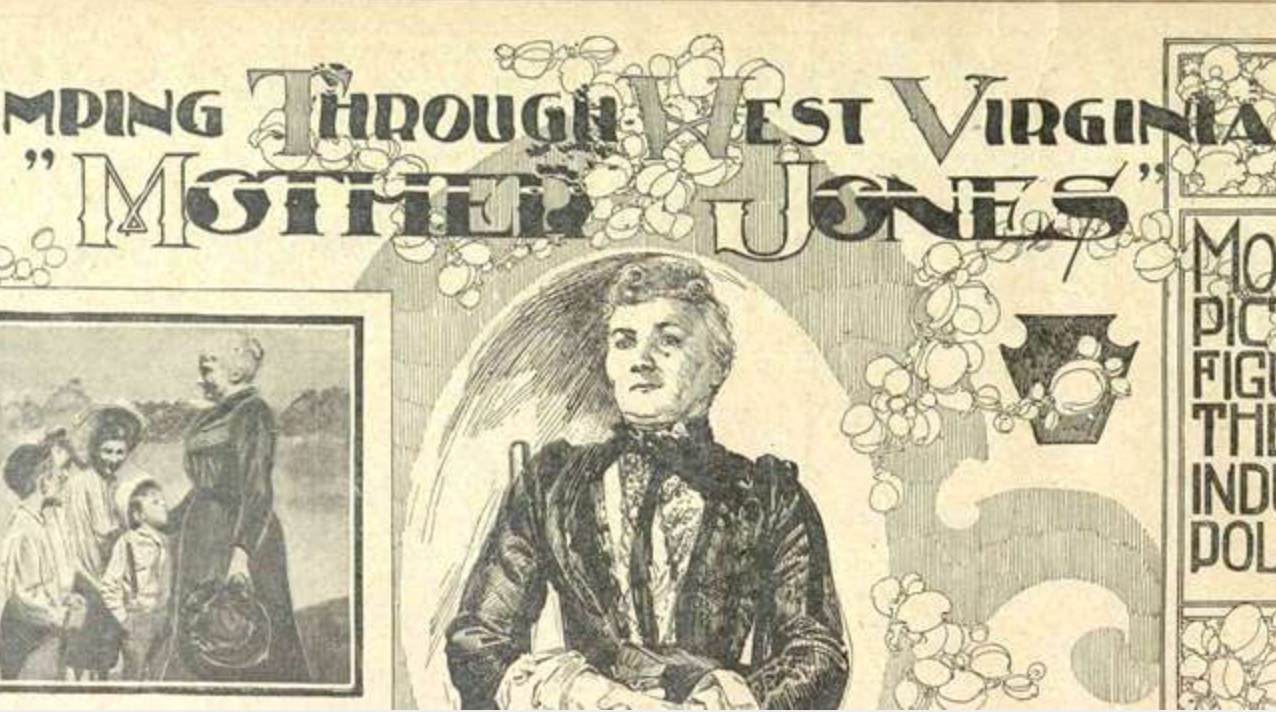

The most dangerous woman in America was a title coined by a United States attorney in West Virginia.

It was 1902, during the largest confrontation in the U.S. since the Civil War, an armed face-off between 10,000 rifle-wielding members of the fledgling coal miners union United Mine Workers and armed mercenaries of West Virginia coal mine owners, in what became known as the Battle of Blair Mountain. In violation of an injunction and in support of the striking and beleaguered coal miners, Mother Jones was arrested – again – and during the court proceedings the prosecuting attorney told the judge that this woman is “the most dangerous woman in America.”

As a labor activist, there had been no other woman as outspoken and effective as Mary Harris Jones. During a time before unions had been formed, before workers were protected from the tyranny of the robber baron bosses who’s bottom-line concerns were only for their profits, “Mother” Jones was “the grandmother of all agitators.” A time when industries pressed workers to beyond their limits, when bosses were far removed from the plight and working conditions of employees, Jones believed that working men deserved a wage that allowed women to stay home to care for their kids.

Born Mary Harris Jones in Cork, Ireland, sometime in the 1830s (she was baptized in 1837), her family immigrated to the US in 1836 at age 6. Her family settled in Michigan, where one of her first jobs was teaching in a convent in Monroe, Michigan. Back in Ireland, her mother was considered an Irish rebel. Mary Harris would follow in her mother’s footsteps, and she would do it admirably.

Mother Jones was a true warrior. Standing 5 ft tall she was feared as a pro- union supporter and defender. Big business hated unions, especially during the industrial age when 9% of the country controlled 75% of the wealth. The mogul owners of Mining, Railroads and Manufacturing got rich while the factory and manual laborer were pushed to their human limits.

TWO GREAT LOSSES

After teaching at the convent in Michigan, Mary Harris opened a dress shop in Chicago. Later she moved to Memphis and married George Jones, an iron worker. They lived in Memphis until 1867 when her husband and four small children died from yellow fever. With her family gone, she helped many other suffering Memphian’s. She returned to Chicago and once again opened and operated a dress shop until 1871 when the Great Chicago Fire destroyed her business and home.

After these two great losses before the age of 40, Jones became evermore passionate for workers’ rights, going after anti-union factions with a vengeance and making bosses’ lives miserable. Her motto became “Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living.” She was fiery in her causes and she developed the heart of a tiger. The snarl of her language could make a sailor blush, and she used her strong language to get national attention.

INSPIRED BY THE GREAT RAILROAD STRIKE OF 1877

One of the first major episodes of labor unrest occurred in the railroad industry. In what was sometimes called The Great Upheaval, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad resulted in labor riots between July 19th and July 30th. More than 61 people died and 139 were arrested as pre-unionized railroad workers fought over wages that had been reduced for the third time by 10% more during an economic downturn.

The barons of power owned all the major newspapers and controlled the news outlets, and used the national media to suppress or make light of the news. They owned their own police force, the Pinkertons, who were known for the ability to break strikes and keep the workers quiet. During the strike, several governors used the state militia to quell striking and rioting mine workers. The killing workers by the militia was not uncommon.

It has been said that the 1877 strike further inspired Mother Jones.

WEST VIRGINIA & OTHER ACTIONS

At the heart of her activism, West Virginia became one of her many battle grounds. From the website Mother Jones Museum:

In West Virginia, Jones contributed significantly to the United Mine Workers of America formal commitment to bridging racial and ethnic divisions. This interracial union drive preceded her involvement, and workers had attempted to organize there since the 1880s. While the UMWA union constitution opened its ranks and pledged non-discrimination, the union leadership was northern European whites. Jones condemned white supremacists in the union, and argued that the black miners of West Virginia were the best trade unionists. She worked with radical Italians and other ethnic groups who were firmly committed to building a union that lived up to its constitution. When an African-American woman, impressed with Mother Jones commitment to the cause, suggested she would kiss Jones’ skirt hem in gratitude for her contributions, Jones refused: “Not in the dust, sister, to me, but here on my breast, heart to heart.” A friend observed that Jones “is above and beyond all, one of the working class. . . Wherever she goes she enters into the lives of the toilers and becomes a part of them.”

From “West Virginia” in MotherJonesMuseum.org

Mother Jones’ actions in support of the mine workers earned her the name, Miner’s Angel. Through her spirit, grit, and tenacity, she inspired the workers to resist and persist in organizing as collective bargaining units.

In May 3, 1886, she took part in the Haymarket Riots. At Chicago’s Haymarket Square, a rally was organized by labor radicals and more than a 1000 workers showed up at the Cyrus McCormick Company to protest the killing and wounding of several workers by the Chicago police during a strike the day before at the McCormick Reaper Works. Firebombs were thrown at the police, many were injured, and workers were shot. The press blamed the Knights of Labor for the incident.

In 1894 she was part of the “Debs rebellion,” siding with the American Railway Union, in the strike that became known as the Pullman Strike.

In April 20, 1914, she involved herself in the Ludlow massacre and the Colorado Coal Miners’ strike.

Mother Jones spent many nights in jail all over the country. She was once sentenced to 20 years in prison for inciting a riot. During the entire rest of her life she was on the forefront of the labor struggle. Through her personal losses, she dedicated her entire life in service to humanity. She went after big business wherever she saw injustices. She accused the Nestle company of sending to underdeveloped countries inferior, watered-down canned milk that was served to babies.

In 1903, when more than 2 million U.S. children were working in factories 12 hours a day, 6 days a week in terrible conditions, she brought attention to the nation of the offenses of child labor. Among many changes she brought, she can be thanked for child labor laws, which did not exist until she came along.

She was a crusader in the lives of African American children, and to the oppressed. She would fight for the underdog wherever there was trouble forming, and she was known to everyone in America as a defender of the weak and ignored.

In the course of her life wherever there was injustice she was there right in the middle of she is a true American Hero.

Mother Jones died November 30, 1930 in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Read more of her life and legend at the Mother Jones Museum.

(Library of Congress)